Bowie and Iggy haunted the gay bars, beer houses and discotheques of Berlin, downing the local König-Pilsener brew in heroic quantities. One night, Iggy went to a punk club where a model of the Berlin Wall was prophetically smashed to pieces. On another boozy occasion, he stumbled onstage to deliver half an hour of Sinatra songs before a bewildered cabaret crowd hauled him off.

“I was drunk as hell,” Iggy later admitted.

New music was never far away either.

“Germany was not a musical backwater,” Bowie insists. “Apart from the local regeneration, every so-called cutting-edge act came through Berlin. Remember, Berlin was the ‘home’ of cool and black clothes. Art bands dreamt of playing Berlin.”

After an initial spell at the Hotel Gehrus, Bowie and Coco found an apartment in the late summer of 1976 in the elegant, bohemian district of Schöneberg, once home to Christopher Isherwood. Though modest by rock-star standards, this dark, wood-panelled hideaway in a faceless tenement block was in fact a seven-room mansion flat with an office, a studio, plus bedrooms for Coco and Iggy. Bowie slept under one of his giant Neo-Expressionist paintings of controversial Japanese author Yukio Mishima.

“155 Hauptstrasse, second floor,” Bowie recalls to Uncut. “Knock hard because the bell sometimes doesn’t work. Ig eventually moved in with a bird next door.” Iggy’s girlfriend was diplomat’s daughter Esther Friedmann. Often they’d blast off in Esther’s Volkswagen into the flat, wooded lakeland around Berlin. Iggy loved the “rinky-dink villages full of strange old German people. We used to get lost. I like to go out and get lost and be in places made of wood, just to wash every shred of America off. Taking a walk was like taking a shower.”

Bowie enthuses about the growing sense of well-being which Berlin brought. “Some days the three of us would jump into the car and drive like crazy through East Germany and head down to the Black Forest, stopping off at any village that caught our eye. Just go for days at a time. Or we’d take all-afternoon lunches at the Wannsee on winter days. The place had a glass roof and was surrounded by trees and it still exuded an atmosphere of the long-gone Berlin of the ’20s.”

Bowie, Iggy and Coco shopped for caviar and chocolates at the Ka De We department store in West Berlin. At night, David says, they’d “hang with the intellectuals and beats at the Exile restaurant in Kreuzberg. In the back they had this smoky room with a billiard table, sort of like another living room, except the company was always changing.”

Berlin’s isolation behind the Iron Curtain also lent the city a chilly frisson of Cold War gloom. Ricky Gardiner, the Edinburgh-born guitarist who played on Low and Lust For Life, recalls driving towards this Oz-like oasis along the fiercely guarded motorway corridor through East Germany. “The autobahn was just as Hitler had built it,” he says. “It had not had any repairs. The broken concrete slabs had taken on a tectonic plate-like life of their own and we bounced from slab to slab. The autobahn was occasionally crossed by overhead walkways. Here, small groups of people would gather to watch the affluent West exercising freedom they could only dream about. Their dress was drab and colourless. They had the demeanour of inmates of some restrictive institution.”

Tony Visconti, who co-produced all three of Bowie’s Berlin albums, remembers the city as a psychotic theme park. “The impending danger of the divided military zones, the bizarre nightlife, the extremely traditional restaurants with aproned servers, reminders of Hitler’s not-too-distant presence, a studio five hundred yards from the Wall,” he says. “You could’ve been on the set of The Prisoner.”

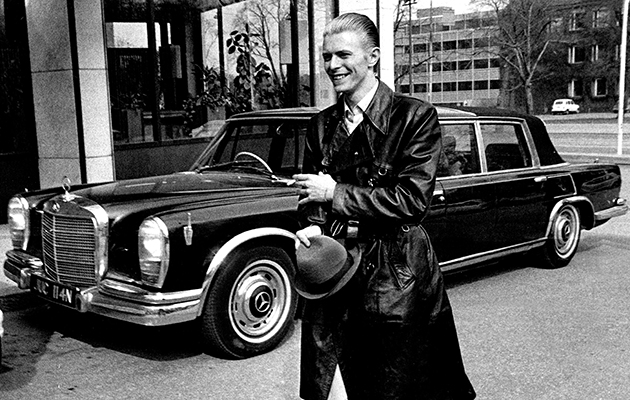

Bowie called Berlin his “clinic”, a therapeutic experiment in chemical and spiritual detox. He grew a moustache, got a crew cut from Visconti, took to dressing like a Polish peasant and cycling around the city unrecognised. This, he explained, was the perfect antidote to “that dull greeny-grey limelight of American rock’n’roll and its repercussions – pulling myself out of it and getting to Europe and saying: ‘For God’s sake re-evaluate why you wanted to get into this in the first place. Did you really do it just to clown around in LA? Retire. What you need is to look at yourself more accurately. Find some people you don’t understand and a place you don’t want to be and just put yourself into it. Force yourself to buy your own groceries…'”