"My complete being is within those three albums." Rob Hughes and Stephen Dalton uncover the complete story of Bowie's life-saving escape to Berlin. How he turned Iggy Pop into a health freak, embraced Brian Eno's "oblique strategies", documented Tony Visconti's indiscretions, and made a fearless and...

While punk swept the rock world, Bowie was one of the few ’70s titans to maintain his credibility. “Whether it was my befuddled brain or because of the lack of impact of the English variety of punk in the US, the whole movement was virtually over by the time it lodged itself in my awareness,” he says. “The few punk bands I saw in Berlin struck me as being sort of post-’69 Iggy and it seemed like he’d already done that. Though I regret not being around for the whole Pistols circus as that kind of entertainment would have done more for my depressed disposition than just about anything else I could think of.”

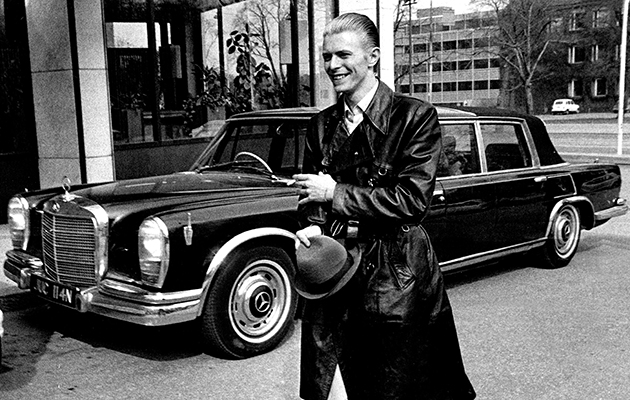

Bowie’s association with Iggy probably helped protect his reputation during the Stalinist purges of punk. His savvy decision to play keyboards for Iggy on The Idiot tour in early ’77 only underlined this dressed-down, man-of-the-people Dave. After recruiting Low guitarist Ricky Gardiner and American rhythm section Hunt and Tony Sales, later of Tin Machine, tour rehearsals took place in a screening room at Berlin’s legendary UFA film studios. “Fritz Lang worked there before the Nazis took over,” Iggy explained. “They still had all these wonderful German Expressionist films just sitting in cans rotting, because they still can’t figure out the politics of who should get them.”

Beginning in Aylesbury on March 1, the British shows were greeted by what Iggy called “a frenzied hail of gob”. Cementing his punk connections, Bowie and Iggy also met up with Johnny Rotten and Sid Vicious in London. “John was quite in awe of Jim [Iggy],” recalls Bowie, “but Sid was near catatonic and I felt very bad for him. He was so young and in need of help.”

As Sid succumbed to heroin, Iggy shunned it. Although he d later relapse, Berlin had temporarily cleansed his system, turning him into a “health freak”. The shot of a maniacally grinning Iggy that Andrew Kent took during a BBC interview, which later became the Lust For Life cover, caught Pop’s new mood of energised optimism. Even so, Bowie later confessed that the tour was far from drug-free. “I kept wanting to leave the tour to keep off drugs,” he said in 1993. “The drug use was unbelievable and I knew it was killing me, so that was the difficult side of it. But the playing was fun.”

Bowie finally overcame his long-standing fear of flying to play US dates with Iggy. The first leg of the tour broke up in late April in LA, where Bowie apparently went on a night on the tiles with Mick Jagger. Then both he and Iggy returned to Berlin to work on Iggy’s Lust For Life, recorded in a three-week frenzy at Hansa By The Wall studios. Iggy took a more dominant role than on The Idiot a year before: “The band and David would leave the studio to go to sleep,” he later recalled, “but not me.”

Bowie confirms Iggy’s claims that the bruising, percussive, invincible title tune was written by him on a ukulele in front of the TV at his Schöneberg apartment, its stuttering rhythm inspired by the Morse-code beat of the Allied Forces Network theme. But its fellow future classic, “The Passenger”, popped into the head of guitarist Ricky Gardiner during an idyllic spring walk. “David, Iggy and myself convened at David’s flat in Berlin to pool ideas for Iggy’s next album,” says Gardiner. “David asked me if I had anything. I didn’t realise they wanted material so I had nothing prepared. However, I remembered the chord sequence. I played it into Iggy’s little cassette machine on my unplugged Strat. He returned the next day with the lyrics complete.”

Iggy resumed touring without Bowie in late summer 1977. By June, David was back at Hansa to make what many consider to be his masterpiece: “Heroes”. Most of the Low players were recalled – Visconti, Alomar, Davis, Murray. Eno was once again musical catalyst and sonic prankster, providing “guitar treatments” and playing synth. But unlike Low, Eno was involved from the start and his experimental methods were now embraced with confidence and vigour.

Hansa’s elegantly shabby Studio Two, a cavernous room that Bowie christened “The hall by The Wall”, had seen service as a Nazi social club. “It was a Weimar ballroom,” Bowie says, “utilised by Gestapo in the ’30s for their own little musical ‘soirées’…”