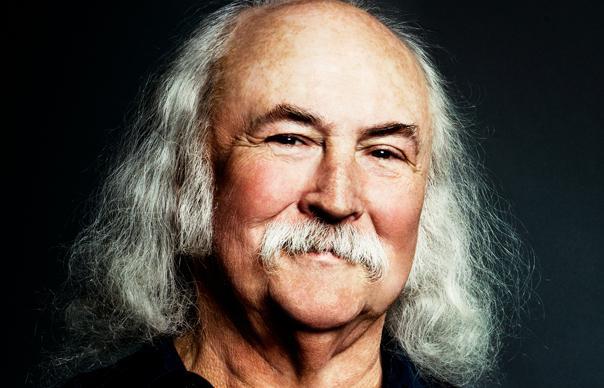

As the Croz prepares to release a new solo album - his fourth in five years - and with two solo UK shows imminent, I thought I'd post my interview with him from our October, 2016 issue. It was a candid chat - as you'd hope - covering a lot of ground, from his career resurgence (he was about to relea...

Lighthouse is your second album in 2 years: you’re on quite a roll at the moment.

It’s actually even worse that that. It’s three albums! Croz was a year and a half ago. Lighthouse, that’s finished, that was me and Michael League, who’s the composer and bandleader for Snarky Puppy. Now I’m just about done with another one with my son James, who produced Croz. It’ll be a band record mostly but there’s one Joni Mitchell song on there where it’s just him on piano and me singing.

Which Joni song?

“Amelia”. Tasteful dude, me.

What’s the appeal of collaboration to you?

I like to write with other people because they always think of something that I didn’t think of. It’s as if you were a painter and you have a palette of colours: if you work with somebody else you’ve doubled the palette. I’m not in it for publishing money or credit, I’m in it for making the best music I can possibly make.

Have your writing methods changed much over the years?

Yeah, I don’t do it stoned!

But surely you wrote some pretty good songs while you were stoned?

Totally! All of ‘em, until more recently. I want so badly to write. If the muse is going to stop by, I want to have all the brain cells I can herd into one room there and functioning. I want to have the lights on, the windows open and be paying attention. In my world, in singer-songwriter world, if you don’t have a song that you can sit down and play to somebody and make them feel something, you’re not there. I can’t do anything unless I write songs. I can’t make a record and if I can’t make records I don’t have new material to go out and play and I can’t just go out and do my hits. That’s just not ok, that’s not good enough. Even at this late stage of the game.

Your songwriting career started to blossom 50 years ago on Fifth Dimension, after Gene Clark left The Byrds. Had you been stockpiling songs up until that point?

Not really. I was just starting to write. Frankly, I don’t think I was as good as Gene. I got better as it went along. God bless Roger, Gene and Chris and the other guys, I did get the chance to push the envelope a little bit.

“Mind Gardens” is pretty out there, isn’t it?

Yeah! They looked at me pretty funny with that one. “You want to do what?” But I was only just getting born as a songwriter, I don’t think I really blossomed until Crosby, Stills And Nash.

Was it competitive between you, Stephen and Graham?

Sure. Not drastically, but we were young guys with egos and we were songwriters – so of course we were competitive with each other. But the absurd advantage we had is that the three of us write completely differently – and if you add Neil to the mix, that gives you a bunch more colours to paint with. If you stick a song of mine next to a song of Neil’s, they’re different texturally and ideologically in every way. That makes for good records.

How would it go down? Would you all gather at someone’s house, bring your guitars and pitch songs to one another?

It wasn’t a formalised thing, but yes. As soon as we had a song, we’d run to the other guys and say, “Hey, listen to this!” They were my favourite people to show off for. They knew what I was capable of and they knew that if they thought a song was good, it probably was. We did that for each other and we would pick from the pool of songs that the four of us had, or the three of us had, and figure out what the record would be and what we were going to play live.

What did you make of Miles Davis’ cover of “Guinnevere”?

At first, I didn’t get it. He came up to me in New York and said, “Hey, are you Crosby?” I said, “Yes, sir.” He said, “I’m Miles.” I said, “I know.” He said, “I cut one of your tunes.” At which point, I choked on my tongue, completely fell down and my brain ran out of my nose. I said, “Whoa, which one?” He said, “‘Guinnevere’.” I said, “Holy shit…” He said, “You wanna hear it? Follow me.” He and this girl with legs up to her neck got into this Ferrari and drove to a brownstone halfway up Manhattan. I went with them. Miles played it for me, but I didn’t get it because there’s no recognisable part of “Guinnevere” in it. I was more concerned about my tune than I was in the honour of the fact that he used it as a starting point for one of his records. I was kind of snotty about it. But now, obviously, I am completely fucking thrilled.

You write very jazz, he was jazz…

There’s more history with Miles than people know. When we tried to get signed to Columbia as The Byrds, they didn’t know what to make of us. You’ve got to understand, the guys running record companies back then were failed shoe salesmen. Absolutely wouldn’t know a song if it bit them in the nose. Miles was on Columbia, so they went to him, played him the Byrds demos and said, “What do you think of this?” He said, “Oh, yeah. Sign them.” So he was responsible for Columbia signing The Byrds. Nobody knows that. You’re welcome.