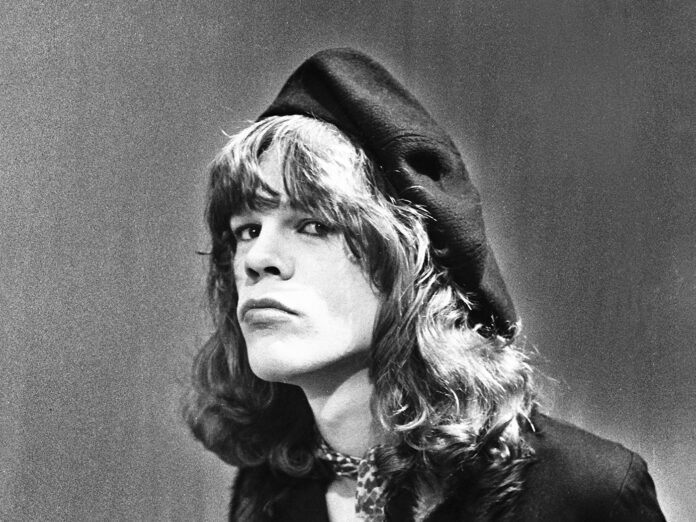

From Uncut’s July 2023 issue, Uncut’s final interview with David Johansen, the New York Dolls frontman turned bouffant nightclub act, country-blues singer and more…

Sipping PG Tips from a dainty blue-and-white teacup, David Johansen considers the long, strange journey that has taken him from high-heeled frontman of the New York Dolls to bouffant nightclub act, country-blues singer and beyond. “There are certain phases in the history of New York, especially in my life,” he says, “that I can look back and say, ‘Yeah, that was really something.’”

This month, several of these glorious incarnations are celebrated in Martin Scorsese’s Personality Crisis: One Night Only – a documentary that covers the span of Johansen’s work, both before, during and after the Dolls. Speaking today over Zoom, Johansen very much inhabits the role of New York music’s grandee, a veteran player who’s navigated his way from downtown scenester to uptown habitué. Accompanied, off-camera, by his wife Mara, who supplies him with a steady diet of biscuits, he chooses his words carefully, rich and gravelly voiced. With his hair hanging down past his shoulders, he still cuts a distinctive, wiry figure.

Johansen’s trajectory has been almost as profound as the transition made by New York itself since he first became an active participant in the city’s counterculture during the late ’60s. Pre-Dolls, he rubbed shoulders with the likes of Abbie Hoffman and Harry Smith in the semi-mythical avant-garde scene; post-Dolls, he performed as a solo artist, before reinventing himself as club singer Buster Poindexter, whose jump-blues repertoire of material has produced four albums and one unexpected and not entirely welcome chart hit, the calypso “Hot Hot Hot”.

In Scorsese’s film, Johansen appears in performance as Buster. As a character Poindexter could be restrictive, but in Johansen’s hands he becomes liberating, allowing the artist to have a little more fun than being simply himself. “Yes, it is [liberating],” he agrees. “Of course, it’s really David. David is Buster and Buster is David. The thing is, sometimes you can have a conceit. Most people do it, but they don’t change their name. You have this character that is like a warrior who goes into battle for you. You don’t have to censor yourself too much or whatever because it’s his fault. Almost anybody who goes on stage does that.”

The core of Scorsese’s film is a series of shows that Johansen played at New York’s Café Carlyle in January 2020, with Johansen-as-Buster performing the Johansen songbook, interspersed with new interviews filmed by his stepdaughter, Leah Hennessey. Scorsese and Johansen go way back – they both broke out in 1973, the year of Mean Streets and the Dolls’ riotous debut album. It’s a period Scorsese revisited separately in Vinyl, his short-lived series about a New York record label, whose debut episode included a replica Dolls gig at their regular haunt of the Mercer Arts Center.

“Scorsese is an old friend of mine,” confirms Johansen. “Over the years, I have done a few projects for him. I sang songs for Boardwalk Empire, old-timey songs. Stuff like that. He used the first Dolls record to rile some of the guys up on the set of Mean Streets before they had a fight scene.”

The film makes a subtle case for Johansen as representing something special about New York culture, an accessible avant-garde, one that never takes itself too seriously but isn’t content to simply play the clown. There is another side to this, of course; by letting Johansen tell his marvellous story, mostly without additional talking heads, Scorsese’s film implicitly reminds us that Johansen is the sole surviving New York Doll. He has outlived his bandmates Billy Murcia, Johnny Thunders, Jerry Nolan, Arthur Kane and Sylvain Sylvain; Murcia, Thunders and Nolan died unnaturally young – “Heroin destroyed everything for the Dolls,” Johansen has admitted. But in some respects, Johansen bears his status as last Doll standing lightly; one of the increasingly few remaining vestiges of a vanished 1970s New York – a creative spirit far too singular to be confined. “It’s not like I’m filled with trauma for the past or anything,” he says.

UNCUT: Scorsese has made documentaries about George Harrison, the Stones, The Band and Bob Dylan. You’re in illustrious company, then.

DAVID JOHANSEN: I guess… or they are! I was doing this show at Café Carlyle, which is a fancy joint, an old place in the Carlyle Hotel in New York. We’d been on the road with the second version of the Dolls for eight, 10 years. We were going to do one show in London and ended up on the merry-go-round. That was winding down and I wanted to stay in New York for a while, re-establish friendships, things like that.

In around 2015, 2106, I decided to put a repertoire together and called it Buster because I wasn’t doing songs I wrote, I was doing songs that I dug. It was a much more mature version of the original Buster – Buster at this age. We started playing the Carlyle twice a year, two weeks at a time. You could live in the hotel, which was kind of a dream because it’s the schlep that kills you, you know what I’m saying? Taking the elevator to work is my dream.

What happened next?

They invited us back. I was in this mood where I didn’t want to have to learn 20 new songs, because you have to do a different show each time. So I thought I’d sing songs I wrote because I knew them already. It was a big success. We wanted to keep it going and were thinking about doing a theatre on Broadway. Mara called Marty to invite him to the show to give us some suggestions about where we could extend this thing. He wasn’t the only person we asked, but he was, I guess, the only major industrial filmmaker. He came and then he said he wanted to shoot it. Mara’s reminding me that I said no.

You said no to Martin Scorsese?

I wanted to do it on stage. I felt that if you show it on TV, that’s the end of it. I was having a lot of fun and I wanted to keep it going. But eventually I acquiesced. I didn’t want to be like Charley Patton. Charley Patton didn’t want to make records because he was afraid everybody would steal his act.

Describe the show for people who haven’t seen the film…

This act is pretty unique. It’s kind of a New York-centric kind of an act. I’ve tried taking it out and it doesn’t work as well. We set it up, we did like three nights, and he shot two of them I think. Then he and David Tedeschi started going through archives to put something together. I tell all these stories in the show – they wanted some stuff to go with that and enhance the movie. It doesn’t cover everything I do, but there’s a good chunk of it. When I watched it, I didn’t cringe that much. That was good. Sometimes I feel like an idiot when I see what I was capable of.

How did Buster start?

Innocently enough in this little saloon in Gramercy Park called Tramps. They used to have a back room and the guy who ran Tramps, Terry Dunne, who was an Irishman, he used to bring in legendary blues singers. This was in the late ’70s and ’80s. He would have like Joe Turner, who would do a month and live in a room upstairs. He had Big Maybelle, Big Mama Thornton, all these amazing acts. I realised they didn’t have anything on a Monday. I had all these songs that I would listen to in the van on the road to tune out my travelling companions, and at that time I was really into the jump blues thing. I used to call it the pre-Hays Code rock’n’roll. I made a little show, a piano player, a guitar player. Just the three of us.

Anyway, this became a big success. It was a groovy scene. People would drop by when they were in town. It did a lot for my voice. It meant I could tell jokes. I was free, I didn’t have to do anything I didn’t want to. When I did the Johansen thing – and I think about this after the fact – I came to resent it, this side of me with no shadows. Buster is more integrated.

Was there a danger of losing that freedom after breaking out of Tramps?

I did lose it. I was down in Tortola or something and that Arrows song “Hot Hot Hot” was playing all the time on the radio. That period of soca, late ’70s and early ’80s, I loved and I still love. We started doing that song and people liked it, I liked it, but when we recorded it that was the end. Oh my God, don’t tell me I have to keep doing this? So that was that, and I went on to do the Harry Smiths to free myself.

Going back to ’73, was there an overlap between Mean Streets and the world of the New York Dolls?

If you played that film in Duluth, people would be, “Oh, my God. What is this?” but when you grew up in it, it wasn’t anything. It was just what it was. I remember the first time I saw the movie. Syl and I were walking down the street and there used to be this arty cinema over on 5th Avenue just south of 14th Street, and we thought let’s go inside and cool off. The movie had already started and at first I thought it was a documentary. I realised after a while it was a movie of course, when I heard the music. Scorsese plays his music loud in his movies. We had a mutual appreciation. There are a lot of artists in New York who have a lot of respect for each other and can kind of joke around with each other.

Pre-Dolls, the film picks up that overlap between the hippies and punk.

New York hippies had a lot of punk attitude. They didn’t have much patience for things. It was different to the West Coast. It’s greedier in New York. The Fillmore East was such an insane place. Gangs would take it over and demand certain things from Bill Graham. I remember scenes that went down there that were so crazy. It was very animated.

Debbie Harry is in the audience at the Carlyle. When did you realise the influence the Dolls had on the bands that followed?

Never. I don’t take any hubristic pride in any of that. I hear it from other people but it just goes through me. There was nothing happening in 1971, early ’72. There was no place to play. The scene was still happening on the street. We, the band, sort of fell together and started looking for places we could play. They had these draconian laws that went down in the late ’60s. When I was a kid, MacDougall Street was heavenly, there were so many clubs and great bands playing. Then they passed these Cabaret Laws, and all those places closed. It was like a ghost town. We had an ambition to get something going again, which I guess we did. It was like having to go to the forest to chop down all the trees to build the stage and put up signs around town – we had to create things.

How did you get that break?

I knew this guy, Eric Emerson, who was in a band called The Magic Tramps. He was an Andy Warhol movie star and he used to wear lederhosen and do the cha-cha dance. They had a gypsy violin player. It wasn’t a straight rock’n’ roll band, it was a Turkish rock’n’ roll band. He said he was playing at this place called Mercer Arts Centre, did we want to play with them? We started playing Tuesday nights at midnight. We started doing that on Tuesday nights and this scene grew up, a very groovy scene. I think about that very fondly but I don’t think of it as influencing other people.

When did things click for you, in the earliest days of the New York Dolls?

When Syl came in and he was bouncing around. He had a guitar case – I said, “Can you play that thing?” and he started playing with us and I just thought, ‘We gotta have this guy in the band.’ He was very energetic. He was the right size! The guy we had before that wasn’t really blowing my skirt up, so to speak. We used to rehearse in this old bicycle store that rented old bicycles for people to go riding in Central Park. So in the wintertime, when there was no bicycle-rental going on, this guy Rusty set up a couple of broken-down amps and some drums so he could rent it out as a rehearsal space. Syl was a good size for John [Thunders], so that was one aspect of it. His personality was another aspect of it. His playing was great. And he was really funny – congenial, y’know? He looked like he would fit in, but it wasn’t like we were going to rehearse in drag.

When did that happen, then?

Well, it was before we became a band. We noticed each other because of how we dressed. If you saw somebody down the street dressed like that you knew it was cool. It wasn’t like we all got together and had a meeting about it. There was a lot of that going on St Mark’s and 2nd.

It must have taken guts to dress like that?

Maybe in certain neighbourhoods, but it was just another part of the scene. There was a lot of innovation going on, you know, there was fashion, film, art, poetry. There wasn’t a lot going on in terms of music, so we became the music part of that scene.

How did you write songs?

I co-wrote “Trash” with Syl, so they tell me! I don’t remember exactly but I always had a notebook so I could write things down, little tidbits. So I had this idea for “Trash” and he started playing this thing: ‘dang-adang-agang, dang-adang-adang, ding-ding-ding-ding waah!’ I thought, ‘Oh that would fit this idea’, it was one of those deals. Usually the first time we play something it’s just about getting ideas and then I’ll go home and write the words. That’s how it worked then, anyway. Syl and I have done a lot of different techniques over the years. Since the reunion, we wrote a lot of songs together, it was a very creative time. Just tickling each other, laughing a lot. We were very tuned into each other as far as writing was concerned – as far as everything was concerned. There was very rarely disagreements about songs.

How critical to the band was Sylvain?

If you took Syl out of that equation, I don’t think it would have been very good, because Syl could really play. He and John went back – of course Billy and him were childhood friends. To play with John… because I always say John was like Sam Andrew in Big Brother & The Holding Company, he would just go. He wasn’t thinking about fitting in with other players. But Syl knew exactly how to get under this guy and support his mania, so to speak. It was a natural

thing, it just kinda clicked. I don’t know if anybody else could have done that, or would have been willing to put up with us.

Malcolm McLaren managed the Dolls towards the end but there’s no mention of him in the film – is there a reason for that?

There’s no particular reason. We used to get clothes from him. Syl was friends with him from being in the rag trade, they had that in common. We used to go to these events, they were called Trunk Shows. There was this hotel on 34th St called the McAlpin and there would be certain times of the year when people who had clothes shops would rent all the rooms. Towards the end we’d go and peruse the merchandise and you could get it for a nice price. That’s when I met Malcolm.

What did you make of him?

I liked him. I thought he was smart. He was political. He checked a lot of boxes for me. We’d go and see him in London. He had his store and on Saturdays these Teds would come down from Glasgow to buy brothel creepers. One time we were in there and the Teds were totally intimidated by the Dolls. We were using all kinds of language and dressed up. Malcolm was in shock because he was scared of the Teds.

That’s one end of the Dolls’ story. But at the other was your unexpected reunion for the 2004 Meltdown festival. How was it, getting the band back together?

I’d done a lot of gigs. I’d done the Harry Smiths and then I was in a band with Hubert Sumlin who played guitar for Howlin’ Wolf. We had Jimmy Vivino on guitar and Levon [Helm] was the drummer. So I was already active when we got back together. I was probably conscious of easing any of their jitters. But you know, we threw that together pretty quick. We rehearsed for three days in New York and then went to London to put on that show. And then it took off. It was fun for a long time but it got tiring. We had to travel pretty rough most of the time, we didn’t have this luxurious lifestyle for gentlemen of a certain age.

By default, you and Sylvain became the custodians of the Dolls’ legacy until his death. Beyond the band, what connected you both?

People loved Syl – he was a really sweet guy, really jovial, and he could get along with anybody. He would say things out of the blue that would be really mindblowing. The way he described things was so beautiful. After the Dolls, when he was still living in New York, he’d be in these living situations… You’d go over to his apartment and it would be like a sitcom – there’d be kids crawling around on the floor, there’d be a monkey loose, people cooking and talking loud, the radio would be on really loud. It was a really fun thing. He knew a million people, he got along with everybody and his take on rock’n’roll was perfect.

Do you think about being the last Doll standing?

I never think of myself unless somebody like you mentions it or I read it somewhere. I don’t really like to think about it too much. It’s just the early band was so long ago, and a lot of the stuff that Johnny and Jerry were involved in was post-Dolls, but in the collective consciousness it sort of melds together. I wasn’t really observing them in that capacity after they left the Dolls and their quest for whatever it was they were looking for.

Following the release of the film, are you planning to do more Buster shows?

I don’t know what happens next. I like to paint. I like to sing. We are going to put out a record of the movie soundtrack. I am thinking of other songs I can record. I’m really good with a deadline. If I need 10 songs by next week, I can do that. So we’ll see what happens.