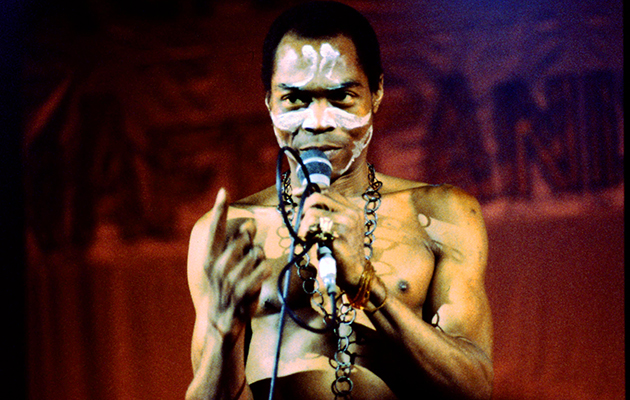

The early ’70s witnessed Fela’s transformation into a West African superstar. On a series of hit albums like 1971’s Why Black Man Dey Suffer and 1973’s Afrodisiac, his music developed a brash, urgent power, bristling with thunderous horn sections, sinuous solos and call-and-response vocals, their scabrous lyrics delivered in pidgin English to cast his message wide. The Afro-Spot, renamed The Shrine and relocated to another part of Lagos called Surulere, became a destination experience, its giddy all-night sessions shrouded in weed smoke, while onstage the band played for hours accompanied by dancers.

From the early ’70s onwards, Fela’s lifestyle and political attitudes presented an increasing challenge to the Nigerian authorities. His advocacy of free sex and ‘Nigerian National Grass’ (widely consumed but highly illegal) became a media scandal, as did his home – a sprawling compound close to The Shrine where he held court to a retinue of friends, musicians, dissidents and hangers-on.

“He did have some friends in high places,” admits Rikki Stein. “He used to have me hold a brown paper bag full of cash that he’d give away to worthy causes. One night when we had run out of money he drove us to a large upper crust house – he drove very fast and never gave way to other cars – and was handed a vacuum-packed block of notes by a guy who was a senator, clearly delighted to help him out.”

“The authorities found it hard to close down Fela because he was of their class,” notes novelist Diran Adebayo. “Plus he was reclaiming an African heritage, which was widely popular.”

Not everyone found the scene to their taste. The late Mac Tontoh, a founding member of London-based Afro-rock pioneers Osibisa, had known Fela since the late 1960s. He was shocked when he visited Fela’s compound in 1973. “We were hearing in London that Fela had 10 cars, a swimming pool and women, as if it’s some great place. When we came there we saw broken cars and a girl pissing at the edge of the pool. I went into a room and saw rats.”

Fela dismissed his old friend’s criticisms – he also gave short shrift to Paul McCartney, in town to record Band On The Run [see panel]. Increasingly, Fela was a man of contradictions. Creatively, he was an autocrat who dictated the arrangements of his tightly drilled band – “to everyone but me,” says Tony Allen – yet Fela’s mischievous sense of humour and generosity were infectious, while his social and political critiques grew ever more pointed on albums like 1975’s Expensive Shit, an account of a failed attempt to bust Fela for weed, and 1976’s Zombie, which lampooned the dumb obedience of the military.

“Fela did some things that really it would have been better if he hadn’t done,” admits Ginger Baker. “He went a little bit over the top. There was a political rally that over 250,000 people attended, at this big stadium they built for the All-Africa Games. 250,000 people, everybody smoking dope. The government were severely worried about Fela, because he was so popular. If he’d have played his cards right, he could well have become the President of Nigeria. We called him the Black President.”

The authorities’ harassment of Fela grew worse. His compound was raided twice in April 1974. Sixty riot police armed with tear gas and axes arrested and beat Fela, leaving him hospitalised. His release from prison was accompanied by a crowd of thousands, and he played The Shrine that night with his head bandaged and his arm in a sling. He also changed his name from Ransome-Kuti, which he denounced as his ‘slave name’ (Ransome had been a missionary friend of his grandfather), to ‘Anikulapo’, meaning ‘one who holds death in his pouch’.

Zombie was the tipping point for the military junta led by General Obasanjo – a former classmate of Fela. On February 18, 1977, around 1,000 soldiers stormed Fela’s compound – now named the Kalakuta Republic and surrounded by an electrified fence. Cars were set on fire, men beaten with rifle butts and women raped, while Fela’s 77-year-old mother, Funmilayo, was thrown from an upstairs window – she never fully recovered and died the following year. The house was burned to the ground, along with the in-house studio and its equipment. Fela and his brother Beko, who ran a free clinic there, were both beaten savagely.

Fela’s daughter Yeni, a teenager at the time, recalls “my brother Femi and sister Sola would stop at Fela’s house on their way home from school, and they told us about the soldiers. My uncle tried to drive my mother and us there but it took hours. We thought it had been a normal raid. What we saw was so bad my mother started to scream. The house had been burnt to the ground and people were walking with their hands in the air, soldiers everywhere…”

One of Fela’s responses was to marry his 27 ‘Queens’, an act of polygamy he claimed was part of African tradition and that by marrying them he was protecting his wives against charges they were prostitutes. With typical contrariness, he divorced them in 1986, saying no man should own a woman’s body. Yeni has ambiguous feelings about it. “I learnt at an early age that men were polygamous, so I just accepted it. As a kid, it was fun having so many stepmothers, though now, at 49, I wonder how my mother Remi, born and raised in England, really felt.”