As an artist, Nick Cave has mastered many different disciplines – musician, novelist and screenwriter among them – but arguably his greatest accomplishment has been the on-going management of ‘Nick Cave’. Like any successful brand operating in a busy marketplace, Cave has reinvented both himself and his music – from the Melbourne punk scene via Berlin and Sâo Paolo to his current domestic arrangement on the East Sussex coast – while the basic tenets of his brand remain consistent: artistic independence, dark Americana, interesting hair. These notions of authenticity and reinvention – and the fine line between the private person and the public persona – are at the heart of this outstanding documentary by visual artists Iain Forsyth and Jane Pollard, who present their film as a day in Cave’s life. His 20,000th day, in fact. The film opens at 7am, with Cave woken by an alarm clock. Forsyth and Pollard follow him on a journey to his office for a spot of writing, a visit to his psychotherapist, some typically robust banter over a lunch with Warren Ellis, a recording session, a trip to the archive, winding up with pizza and Scarface with his sons before a final, climactic gig. Cave airs his thoughts in voiceover (“Mostly, I feel like a cannibal”… “I love the feeling of a song before you understand it”) and drives in his black Jaguar from one appointment to the next accompanied by various passengers: Ray Winstone, Blixa Bargeld and Kylie Minogue. Previously, Forsyth and Pollard have mounted re-enactments of both David Bowie’s final performance as Ziggy Stardust and the Cramps’ 1978 gig at Napa State Mental Institute. 20,000 Days On Earth is a natural successor to these alternative testimonies of reality: a sophisticated exercise in blurring truth and fiction which chimes with Cave's own talent for revealing truths in fictional worlds. A good example is the visit to the psychotherapist Darian Leader, during which Cave discusses his relationship with his late father, his formative sexual experiences and his biggest fear (“losing my memory”). However, while Cave’s disclosures are almost certainly genuine, the setting is not: Leader is not Cave’s psychotherapist and his office is in fact a dressed set. Such crafty smudging continues in the visit to the archive and Warren Ellis’ house, both of which are also sets, although what occurs at each location is undoubtedly ‘real’. As 20,000 Days On Earth progresses, it becomes evident that what we’re watching is yet another marvellous act from Cave. Critically, Cave reveals to Leader that a significant moment in his childhood was being read Lolita by his father, which Cave describes as a “transformative performance”. Transformation is key to the film. Cave explains to Leader that, unbeknownst to him, his father attended one of his earliest gigs; when he later revealed this to his son, Cave Snr revealed he had looked “like an angel” on stage. Further conversations about the transformative possibilities of being a rock star permeate Forsyth and Pollard’s film. Over eels and pasta, Cave and Ellis share a hilarious anecdote about Nina Simone playing the Cave-curated Meltdown Festival (punchline: “champagne, cocaine and sausages”) that digs further into the psychology of performance as a transformative experience. Cave and Ray Winstone discuss the idea that a rock star, unlike an actor, can never truly be ‘off duty’. You might just glimpse in one of his notebooks that Cave has written “terrible performance anxiety, that is what pushes me to lose myself in performance”. A self-confessed “ostentatious bastard”, Cave makes a predictably compelling subject for Forsyth and Pollard, who have worked with Cave since 2008 on a number of video projects. Whether striding purposefully round his home in Brighton, sitting contemplatively at a piano in the studio (filmed during sessions for the Push The Sky Away album), or discussing Bargeld’s departure from the Bad Seeds (one of the film’s most squirm inducing sequences), he is smart and funny, much as you’d expect. Forsyth and Pollard surround him with rich, esoteric detail. The walls of his office are covered in photographs and memorabilia, we see pages from his diaries (the ‘weather diary’ is a particular highlight), a copy of Technicians Of The Sacred sits on a piano. Anyone wondering who the mysterious “Janet” was on “More News From Nowhere”: prepare for revelations aplenty. You want to know what coffee Nick Cave drinks in the studio? “A small one shot latte with one sugar.” It all makes for a fascinating and engaging film, ending with a rousing rendition of "Jubilee Street" recorded at Sydney Opera House, with Cave - carried away, at last, in the rapture of performance, singing over and over: "I am transforming / I am vibrating / I'm glowing / I'm flying / Look at me now". Follow me on Twitter @MichaelBonner. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kV9cobZP4JA 20,000 Days On Earth opens in the UK on September 19

As an artist, Nick Cave has mastered many different disciplines – musician, novelist and screenwriter among them – but arguably his greatest accomplishment has been the on-going management of ‘Nick Cave’.

Like any successful brand operating in a busy marketplace, Cave has reinvented both himself and his music – from the Melbourne punk scene via Berlin and Sâo Paolo to his current domestic arrangement on the East Sussex coast – while the basic tenets of his brand remain consistent: artistic independence, dark Americana, interesting hair.

These notions of authenticity and reinvention – and the fine line between the private person and the public persona – are at the heart of this outstanding documentary by visual artists Iain Forsyth and Jane Pollard, who present their film as a day in Cave’s life. His 20,000th day, in fact. The film opens at 7am, with Cave woken by an alarm clock. Forsyth and Pollard follow him on a journey to his office for a spot of writing, a visit to his psychotherapist, some typically robust banter over a lunch with Warren Ellis, a recording session, a trip to the archive, winding up with pizza and Scarface with his sons before a final, climactic gig. Cave airs his thoughts in voiceover (“Mostly, I feel like a cannibal”… “I love the feeling of a song before you understand it”) and drives in his black Jaguar from one appointment to the next accompanied by various passengers: Ray Winstone, Blixa Bargeld and Kylie Minogue.

Previously, Forsyth and Pollard have mounted re-enactments of both David Bowie’s final performance as Ziggy Stardust and the Cramps’ 1978 gig at Napa State Mental Institute. 20,000 Days On Earth is a natural successor to these alternative testimonies of reality: a sophisticated exercise in blurring truth and fiction which chimes with Cave’s own talent for revealing truths in fictional worlds. A good example is the visit to the psychotherapist Darian Leader, during which Cave discusses his relationship with his late father, his formative sexual experiences and his biggest fear (“losing my memory”). However, while Cave’s disclosures are almost certainly genuine, the setting is not: Leader is not Cave’s psychotherapist and his office is in fact a dressed set. Such crafty smudging continues in the visit to the archive and Warren Ellis’ house, both of which are also sets, although what occurs at each location is undoubtedly ‘real’.

As 20,000 Days On Earth progresses, it becomes evident that what we’re watching is yet another marvellous act from Cave. Critically, Cave reveals to Leader that a significant moment in his childhood was being read Lolita by his father, which Cave describes as a “transformative performance”. Transformation is key to the film. Cave explains to Leader that, unbeknownst to him, his father attended one of his earliest gigs; when he later revealed this to his son, Cave Snr revealed he had looked “like an angel” on stage. Further conversations about the transformative possibilities of being a rock star permeate Forsyth and Pollard’s film. Over eels and pasta, Cave and Ellis share a hilarious anecdote about Nina Simone playing the Cave-curated Meltdown Festival (punchline: “champagne, cocaine and sausages”) that digs further into the psychology of performance as a transformative experience. Cave and Ray Winstone discuss the idea that a rock star, unlike an actor, can never truly be ‘off duty’. You might just glimpse in one of his notebooks that Cave has written “terrible performance anxiety, that is what pushes me to lose myself in performance”.

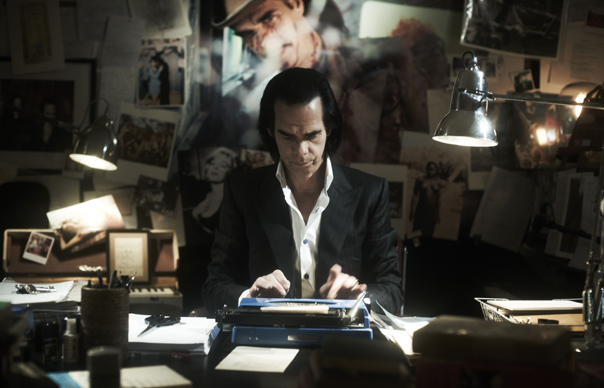

A self-confessed “ostentatious bastard”, Cave makes a predictably compelling subject for Forsyth and Pollard, who have worked with Cave since 2008 on a number of video projects. Whether striding purposefully round his home in Brighton, sitting contemplatively at a piano in the studio (filmed during sessions for the Push The Sky Away album), or discussing Bargeld’s departure from the Bad Seeds (one of the film’s most squirm inducing sequences), he is smart and funny, much as you’d expect. Forsyth and Pollard surround him with rich, esoteric detail. The walls of his office are covered in photographs and memorabilia, we see pages from his diaries (the ‘weather diary’ is a particular highlight), a copy of Technicians Of The Sacred sits on a piano. Anyone wondering who the mysterious “Janet” was on “More News From Nowhere”: prepare for revelations aplenty. You want to know what coffee Nick Cave drinks in the studio? “A small one shot latte with one sugar.”

It all makes for a fascinating and engaging film, ending with a rousing rendition of “Jubilee Street” recorded at Sydney Opera House, with Cave – carried away, at last, in the rapture of performance, singing over and over: “I am transforming / I am vibrating / I’m glowing / I’m flying / Look at me now”.

Follow me on Twitter @MichaelBonner.

20,000 Days On Earth opens in the UK on September 19