As 4AD's deluxe reissue of the sublime No Other is unveiled, we thought we'd delve into the Uncut archive to find this great feature on Gene Clark - originally published in our May 2008 issue (Take 132). Order the latest issue of Uncut online and have it sent to your home! _________________ It's ...

Order the latest issue of Uncut online and have it sent to your home!

CHAPTER ONE: THE FANTASTIC EXPEDITION

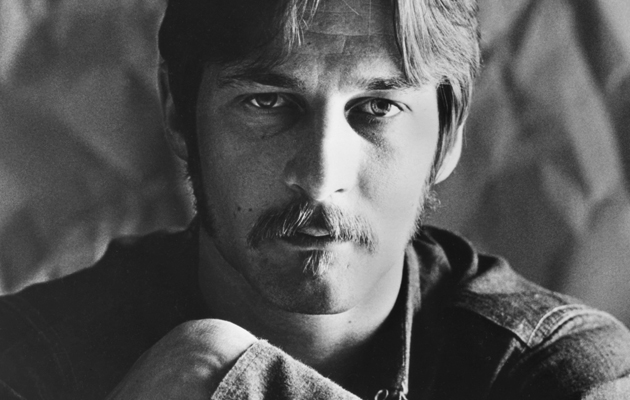

“For whatever level of acceptance he had going in the commercial market, Gene was a star,” asserts Roger McGuinn. Still, nothing quite worked out for Gene Clark once he left The Byrds. If his genius, his poetic songcraft, had sometimes been obscured by the cluster of talents within the band, the pressure of a solo career caused him difficulties, too.

“I think he may have been someone who was really scared to death of being a solo guy,” suggests guitarist Stephen Bruton, who befriended Clark in later years. “He had the ego where he wanted to be a solo guy, but he was really full of doubt.”

Nevertheless, he tentatively had a go. In a 1966 interview profiling the Gene Clark Group, the frontman hinted at a revolutionary future: “In the short time we’ve been together, we’ve worked up a lot of material. It’s kind of a strange sound. We’re working on some things, which are a mixture of country, western, and blues combined.”

In 1966, the short-lived Gene Clark Group – featuring Chip Douglas, Joel Larson and Bill Rhinehart – began a summer residency at LA’s Whisky A Go-Go. Though the image proffered by Sid Griffin of “young Doc Hollidays wearing Bolo ties, playing poppy C&W” is intriguing, Clark’s new material sailed right over the audience’s heads.

All the same, back-to-the-roots country influences were creeping into the West Coast. David Jackson, of country/rock pioneers Hearts & Flowers and later a Clark collaborator, was among the scene’s central players: “You’d go to somebody’s house after a gig and sit around and play until three or four in the morning, maybe pass a joint, drink a beer – but that wasn’t the reason everybody was there. The guitars would come out. It was a give and take, like, ‘Let’s do this one.’ As opposed to ‘Let’s make it sound like a cross between Hendrix and Merle Haggard.'”

Clark’s first attempts to fuse country and rock came when he teamed up with banjoist Douglas Dillard and guitarist Clarence White (ironically, a future Byrd) for 196??’s Gene Clark With The Gosdin Brothers. Clark, a Midwestern farmboy turned pop aristocrat, hardly threw himself full force into the world of steel guitars and Nudie suits, but in among the baroque/pop brilliance of “Echoes” and Rubber Soul-isms of “I Found You” are several twangy nuggets – “Tried So Hard” and “Keep on Pushin'” – that became the seeds of country rock.

“We were all just a little bit ahead of our time,” reflected Clark in 1972, when a revamped version of the album was released. “No country-rock sold well until after 1969. The public was still more ready for ‘Marrakesh Express.'”

“Gene was a country boy,” says McGuinn. “He had a love for that kind of music. I could see that country streak, although he was enamoured of The Beatles.”

With Clarence White in tow, Clark played a few gigs around LA. One lucky soul – WHO IS THIS? – who witnessed a rare appearance at the Ash Grove recalls: “The entire night was three-part harmonies, and it knocked me out. It was also the first time I’d ever seen Clarence with a Telecaster. Prior to that, he’d simply been that amazing flatpicker from the Kentucky Colonels, who played straight bluegrass. They did some Everly Brothers stuff that was stunning.”

Coincidence or synchronicity, LA was soon crawling with longhaired roots-rockers. Gram Parsons’ International Submarine Band arrived from New York. The Nitty Gritty Dirt Band, the Stone Poneys, not to mention Michael Nesmith and Gary Paxton’s stable of insurgent country hopefuls, were gathering steam.

Clark, meanwhile, was rapidly working his way through bandmates and abandoning endless album. Eventually, he and Doug Dillard (just back from a touring stint with, yes, The Byrds) hooked up with future Eagle Bernie Leadon and David Jackson of Hearts & Flowers. Calling themselves the Dillard & Clark Expedition, they sought to mix up country, folk, rock and, especially, bluegrass.

“Gene and Dillard just went all over the place together,” says Jackson, the Expedition’s bassist. “Douglas, being the bluegrass textbook that he is, inundated Gene with everything bluegrass. Gene synthesised that into his style, which had not been bluegrass at all. I thought it really kind of reached a new plateau with the collaboration of Dillard and Clark, at a poetic level.”

Released in Autumn 1968, the band’s A&M debut, The Fantastic Expedition Of Dillard & Clark, was a startling mix of mandolin, dobro, banjo, guitar, harpsichord and plentiful mountain harmonies, anchored by Clark’s silkily soulful baritone.

“Bernie, Doug, and Gene and I just sort of showed up every day, and started playing,” Jackson remembers. “And Gene would be sitting on the couch, not saying much – maybe ‘Hand me a donut’ – he’d have a guitar in his lap… he’d have a melody and some chords maybe, and an hour would go by, and I’d have my bass out, and Bernie would be tuned, and maybe he’d have some lines. That’s how it would go. The first album was not planned, really.”

“Gene responded to the stuff with Douglas and us with his whole heart and soul,” Leadon told Clark’s biographer, John Einarson. “It was embracing the totality of who Gene Clark was, his [Missouri] roots, and [he] got to use his extraordinary lyric and writing ability but without having to try to invent a whole new music, which was what you were sort of expected [to do] in the pop world.”

Things tended to become problematic, though, once the troupe moved out of the living room and onto the stage.

“Gene was not a demonstrative performer,” says Jackson. “He just stood there. In fact, his demeanour was very guarded, and he probably thought that you were not going to like this shit anyway.”

Whether it was stage fright, or another combination of demons, the Expedition’s public unveiling – at West Hollywood’s Troubadour in December 1968 – was a disaster.

“We went down to the Troubadour that Tuesday at 2 o’clock,” Jackson recalls. “We load in, soundcheck. About 3:30 I left, went back to take a nap, had something to eat, took a shower. When I got back, the doorman says ‘You better go next door to Dan Tana’s, get Gene and Doug. They both dropped acid, and they’re sitting in there drinking martinis.'”

“So I go next door, and sure enough, they’re just grinning ear to ear. I just remember a kind of haze occurring, instantly, and going ‘We’re in serious trouble.'”

Jackson remembers the club being packed with fellow musicians, old Byrds freaks, the rock press. “So the lights go down, [Troubadour light man] Dickie Davis says, ‘Ladies and gentlemen, Dillard & Clark!’ When the lights come on, all of us are facing out, but Gene is sitting on his amp, facing the back wall. We make it through the first song, and Dillard picks up the fiddle for the second song. Somehow or another I guess we got Gene off the amp, and standing in front of the mike. We get to the end of the second song, Doug puts his fiddle down on the floor, jumps up in the air, and lands on the fiddle, breaking it. Don Beck, who is our multi-instrumentalist, and a devout Christian, was playing the mandolin. He just looked up at me, and said, ‘Well, that’s enough for me,’ and he walked off stage, never to return.”

The Expedition survived, but the damage was done. There was a second, slightly less dazzling album (Through the Morning, Through the Night), and a stunning non-album single (“Why Not Your Baby”), but the group quickly unravelled. Fiddler Byron Berline, who joined during the group’s latter days, and played with Clark sporadically thereafter, traces their decline: “The biggest problem with that group was Doug and I were wanting to pick more and I think Gene felt sort of left out. He didn’t seem to be happy most of the time but he was very difficult to read, at least for me. Around November 1969 we were invited to play on the Hee Haw TV show. This was their first season and a nice break for any group to get on national TV. Gene didn’t want to go [because of flying] and eventually left the band right after that.”

“Gene had a lack of confidence right from the very first time I ever saw him,” says Jackson. “And then there was heroin later on. You know, obviously, that’s not an end in itself. It’s a symbol of a symptom.”