Order the latest issue of Uncut online and have it sent to your home!

CHAPTER THREE: FEEL A WHOLE LOT WORSE

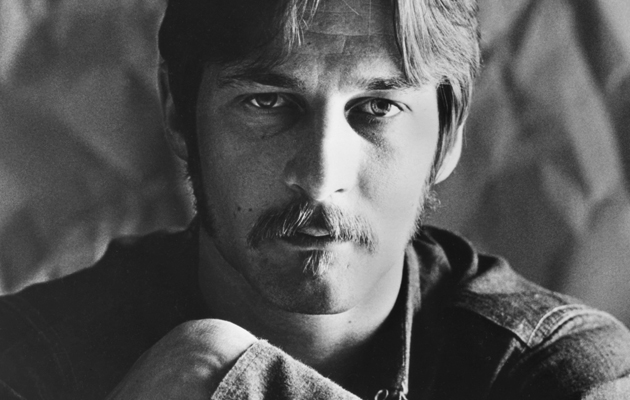

In 1987, after underwhelming records, weary partial reunions of The Byrds, and apparently innumerable doomed projects, Clark finally managed to stage a credible comeback. So Rebellious A Lover sent a jolt through LA’s burgeoning cowpunk scene, an echo traceable back to country rock’s nascent beginnings.

“That album came about as a result of singalong sessions Gene and I had at his house,” partner Carla Olson recalls. “It all evolved naturally. It was that sparse acoustic approach that we sought to duplicate in the studio. Atmospheric, western, stark and voices, voices, voices. People tell me to this day that it inspired the alt-country generation.”

Any momentum, though, was short-lived. The excesses were beginning to catch up with Clark: stricken with ulcers, the result of years of heavy drinking, he had his stomach and much of his intestines removed during surgery in 1988. A year later, when Tom Petty repaid his debt to The Byrds by covering “Feel A Whole Lot Better” on Full Moon Fever, Clark suddenly started receiving the sort of royalty cheques he hadn’t seen in years.

Rather than capitalising on his renaissance, Clark immediately slipped back into his worst ways. He cancelled what could have been a momentous comeback UK tour, and set about partying in LA like it was 1966 all over again.

“Gene, when he was doing that shit, it was black,” remembers Bruton. “When he’d call me during the daytime, everything would be cool: ‘Hey I’ll be playing McCabe’s, wanna come down and sit in?’ ‘Oh yeah, Gene, I’ll be down there no problem.’ Everything was fine. Then I’d call and on the phone he’d [whisper, in a husky voice], ‘I’ll call you back.’ I’d just be saying to myself, ‘Gene, please don’t do this.'”

“Gene had an aversion to doctors,” observes Einarson, his biographer, “and having grown up in a family that dealt with mental illness and bipolar disorder by self-medicating with alcohol, always believed he could cure himself. He would go on and off that wagon frequently. In his last year or so he would binge then cleanse himself by going cold turkey and go on a fitness jag for three weeks. The trouble was that in his mid-40s, and after decades of abuse to his system, his constitution could no longer stand these routines.”

Gene Clark died at his Sherman Oaks apartment on May 24, 1991 – Bob Dylan’s 50th birthday. “He got a bunch of success,” reflects Bruton, “and I think he started thinking that he could live that same way again – that somehow he was an exception to the rule. Everybody thinks they’re immortal. He stopped, and turned around, and stared back at the sun. Whatever you wanna call it…”