Most of us generally assume that the story of Ardent Records, crucible of Memphis rock, begins at John Fry's studio in the early '70s, around the time Alex Chilton ambled his way into Big Star. In reality, though, Fry had been releasing 45s out of Ardent Studios since 1959 (The Ole Miss Downbeats' h...

Most of us generally assume that the story of Ardent Records, crucible of Memphis rock, begins at John Fry’s studio in the early ’70s, around the time Alex Chilton ambled his way into Big Star. In reality, though, Fry had been releasing 45s out of Ardent Studios since 1959 (The Ole Miss Downbeats’ honking version of “The Hucklebuck” being the first).

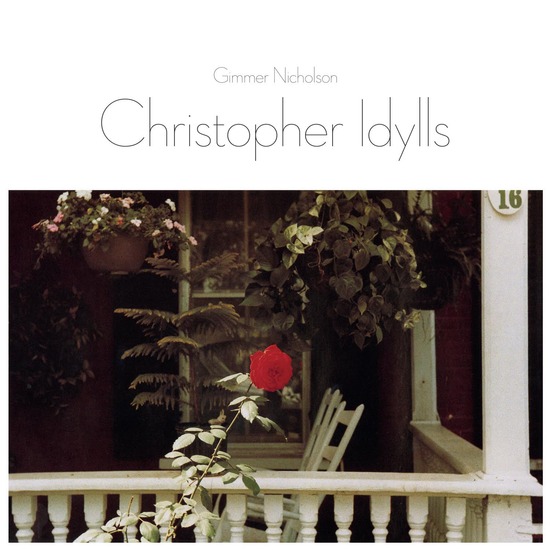

What came between primitive rock’n’roll and genre-defining power-pop is a little murkier, but the first full-length album planned for release on Ardent was, of all things, a proto-ambient collection of guitar instrumentals, played by a jobbing musician-cum-guitar maker called Larry “Gimmer” Nicholson. Nicholson moved in a local music scene populated by rowdy figures like Jim Dickinson, Sid Selvidge and Ronnie Milsap, but it seems he had an epiphany at some point in the mid-’60s, when he witnessed a Memphis show by John Fahey in his Blind Joe Death phase. “Gimmer saw that,” remembers Jimmy Crosthwait, a musician, artist, and puppeteer quoted in Andria Lisle’s superlative sleevenotes, “and he went off by himself for about a year and re-emerged with the ability to play circles around Fahey.”

A bold claim; and while Christopher Idylls doesn’t quite bear it out, Nicholson does come across as a remarkably sensitive and innovative musician, suddenly at odds with the Southern music tradition that surrounded him. The six pieces were actually composed and demoed in San Francisco, where Nicholson moved for a while. In 1968, his brother Gary handed the tapes to Terry Manning at Ardent, who recalled Nicholson to Memphis and recorded the album using a few guitars and a new delay pedal. Listening to the aqueous, courtly likes of “Charon’s Crossing” now, they sound less like a product of the late ’60s, more a New Age project from a decade later – as if Fahey had become beatific rather than ornery, perhaps, and found a place on the Windham Hill label alongside Robbie Basho.

As the first album release on Ardent, Christopher Idylls would certainly have been incongruous, but it was Nicholson himself rather than Fry and Manning who pulled the release, reputedly unhappy with the mix. In the intervening five decades, the album has briefly surfaced twice: in 1981, on Selvidge’s Peabody label alongside Chilton’s Like Flies On Sherbert; and in 1994, on Manning’s Lucky 7 imprint, with Nicholson’s full collaboration. The guitarist died, a marginal figure to the end, on December 30, 2000.

Before that, though, Nicholson’s masterpiece caused discreet reverberations across the musical landscape. Manning recalls a night in April 1970 at his apartment, playing Christopher Idylls to Jimmy Page (who would return to Ardent in the autumn, to mix Led Zeppelin III) and Chris Bell. On one level, Nicholson’s intimate meditations are a world away from the punch of early Big Star. On another level, though, they act as a kind of ghostly pre-echo of, say, “Watch The Sunrise”; “Here’s the deal,” John Fry told Andria Lisle, before he died, “music brings people together.”