My Bloody Valentine are reportedly returning to active service, Ride are about to start a new run of UK shows... Seems like a good opportunity to post my piece on the history of shoegazing that originally ran in the July 2017 edition of Uncut. Follow me on Twitter @MichaelBonner ________ The gu...

My Bloody Valentine are reportedly returning to active service, Ride are about to start a new run of UK shows… Seems like a good opportunity to post my piece on the history of shoegazing that originally ran in the July 2017 edition of Uncut.

Follow me on Twitter @MichaelBonner

________

The guest list, remembers one visitor, featured the cream of the Eighties pop charts. The venue was Stocks, a sprawling Georgian mansion in the Hertfordshire countryside then owned by Playboy executive Victor Lownes. There, one evening in July, 1984, members of Duran Duran, Spandau Ballet, Frankie Goes To Hollywood and many more were invited to drink champagne, take a dip in the largest Jacuzzi in Europe or even place a bet at the roulette tables. The occasion? A very exclusive party to celebrate the ongoing success of the latest album by the Thompson Twins, Into The Gap. Record Mirror estimated the “Gatsby-style shindig” cost “a cool twenty grand”. Among the attendees, meanwhile, were two 16 year-old friends, Emma Anderson and Miki Berenyi, who had recently struck up an unlikely friendship with Thompson Twins’ frontman, Tom Bailey.

“We were wandering around the place and we saw Robin Guthrie and Liz Frazer,” recalls Anderson today. “We went up to them and said ‘Hi.’ They said that they knew no one there and were quite flattered we knew they were the Cocteau Twins. No one else had really spoken to them. Robin thought they had only been invited to the party as they were ‘twins’ as well.”

The careers of the Cocteau Twins and Lush, the band Anderson and Berenyi formed in 1987, intertwined over the subsequent years. During Lush’s occasional recording sessions with Guthrie, Anderson remembers “eating a lot of Indian takeaways”: a surprisingly robust diet for the music her band made, characterized by gliding, indistinct vocals and gauzy sonics.

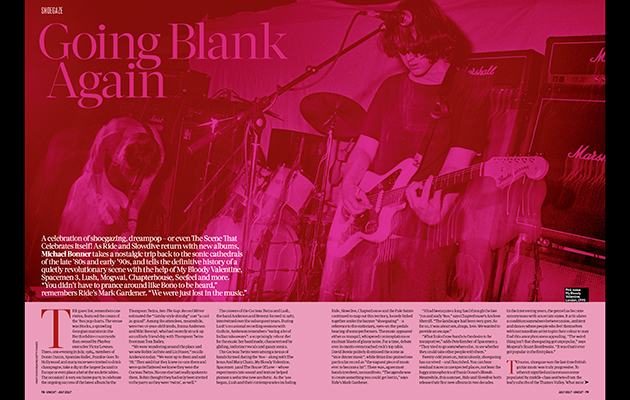

The Cocteau Twins were among a nexus of bands formed during the 1980s – along with The Jesus And Mary Chain, My Bloody Valentine, Spacemen 3 and The House Of Love – whose experiments into sound and texture helped pioneer a seductive new aesthetic. As the Nineties began, Lush and their contemporaries including Ride, Slowdive, Chapterhouse and the Pale Saints continued to map out this territory, loosely linked together under the banner ‘shoegazing’ – a reference to the stationary, eyes-on-the-pedals bearing of some performers. The music appeared either as tranquil, whispered contemplations or exultant blasts of glassy noise. For a time, debate over its merits even reached rock’s top table. David Bowie politely dismissed the scene as “nice dinner music”, while Brian Eno praised one particular record as “the vaguest piece of music ever to become a hit”. There was, agree most bands involved, no manifesto. “The agenda was to create something you could get lost in,” says Ride’s Mark Gardener.

“It had been quite a long haul through the late Seventies and early Eighties,” says Chapterhouse’s Andrew Sherriff. “The landscape had been very grey. So for us, it was about sex, drugs, love. We wanted to provide an escape.”

“What links those bands together is the desire to be transportive,” adds Pete Kember, former frontman with Spacemen 3. “They tried to go somewhere else, to see whether they could take other people with them.”

Twenty years on, miraculously, shoegazing has survived – and flourished. You can hear residual traces in unexpected places, not least the foggy atmospherics of Frank Ocean’s Blonde. Meanwhile, this summer, Ride and Slowdive both release their first new albums in two decades. In the intervening years, the genre has become synonymous with uncertain states. It articulates a condition somewhere between noise, ambient and dance; where people who feel themselves with no immediate artist to pin their colour to may find this amorphousness appealing. “The weird thing isn’t that shoegazing got unpopular,” says Mogwai’s Stuart Braithwaite. “It was that it ever got popular in the first place.”