It is early afternoon on one of the hottest days of the year. Charlie, Astoria’s resident spaniel, lolls in a patch of shade near the conservatory at the top of the riverside lawn. At 12.59pm on June 30, 2015, Gilmour arrives in Astoria’s grounds accompanied by his wife, Polly Samson. He is wearing a panama hat, with a white linen jacket is slung over his shoulder, giving him the air of a diplomat returning from a swish colonial posting. The image isn’t that different from Robert Wyatt’s first impressions of meeting Gilmour 40 years ago at a party at Nick Mason’s home in Highgate’s Stanhope Gardens. “He had a patrician air that I find very unusual in rock music,” he says. “He was dignified, witty. Grown up. I like him, but I’ve always been a little awestruck by him. Not because he’s intimidating, but you feel that he’s listening and watching. His bullshit detector is on ‘alert’ a lot of the time.”

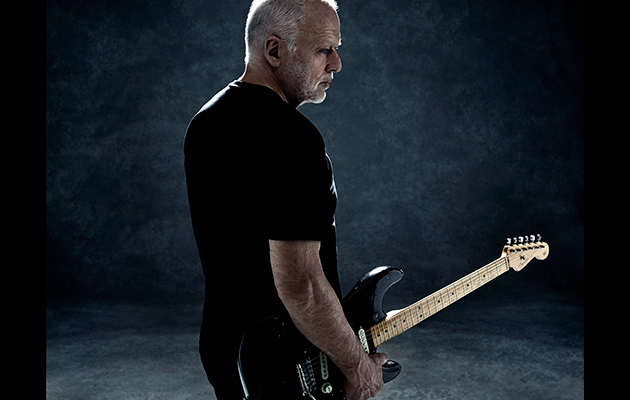

Currently, Gilmour sits in a worn leather office chair in the Astoria studio, his bare feet resting on a sofa that runs underneath the length of the studio’s aft window. He is wearing a black t-shirt and matching loose-fitting trousers while his shoes – a pair of black slip-ons – are neatly arranged by the door. At one point, Gilmour temporarily dons a pair of glasses with bright blue frames to answer his mobile phone. But presently, Gilmour is pre-occupied trying to identify when his solo career truly began. “On An Island was the start of something,” he eventually decides. “Having at that point no real intention of ever doing Pink Floyd again. But life is just changes; you are in particular moods in particular moments. Now I’m living in Brighton, it’s a little more active. I don’t know if one ties those things together, or it’s just luck that these pieces of music chuck themselves at you, and you get on with it.”

Attempting to unravel the history of Rattle That Lock – and establish its place in Gilmour’s singular body of work – proves to be a complicated business, not least because of the record’s intricate timeline; but also because of its more personal and private moments. Phil Manzanera, co-producer of On An Island and Rattle That Lock, estimates that Gilmour has been writing material for this new album over the last five years. But then, Manzanera also confirms that one piano part was recorded 18 years ago in Gilmour’s living room; recently, he recalls, he rang up one delighted musician to inform him that a four-note passage he recorded a decade ago appears on this album.

What is clear, however, is that Rattle That Lock was temporarily set aside so that Gilmour and Nick Mason could work on The Endless River, their tribute to Rick Wright. “It took a lot of time and an enormous amount of effort,” admits Gilmour. “We sat here for months, slogging away, trying to get it into shape. I love it, but it was a bit of a tear to drag myself away from it. Then a month after, getting to grips with going back into this.”

Was it important to close the door on Pink Floyd before releasing Rattle That Lock?

“It’s just one of those timing things,” he insists. “Going back and listening to the material made me think, ‘There are some really nice mementos of Rick’s playing.’ I felt we owed it to the fans to put them together and release it. I thought I could do it in a simpler way – but you know, best-laid plans, eh? Something comes along and you have to deal with it properly. Each thing takes maximum energy and thought.”

Although Gilmour is adamant that he works all the time – principally in his own Medina studio in Hove, East Sussex – he admits, “I’ve got a lot going on. Children. Normal stuff to get on with. So when I can, and when I feel like it, I go and work, track down the little bits and improve them, try to see where they’re going.”

Gilmour’s modest, self-deprecating way might make this sound more casual than it actually is. But Youth – who worked with Gilmour on The Orb’s Metallic Spheres album and co-produced The Endless River – recalls witnessing Gilmour’s fastidiousness in the studio. “His attention to the minutiae is extreme. He’d be twiddling on his own and we’d do lots of takes and we’d spend a lot of time editing, sifting, and then redo again. That process of distillation went really far.”

“When he puts the beam on a track, he’s totally hands on,” says Nick Laird-Clowes, a collaborator since the 1980s. “That EQing, that knowledge of sound, that science brain mixed with his art brain, is crucial to understanding who he is. It’s too much of a simplification, but his father was scientific and his mother was artistic. All the delays you get on the Floyd records, they’re all things he’s worked out scientifically but not at the sacrifice of the artistic and melodic content.”

“He’s very, very meticulous in the studio,” agrees Robert Wyatt. “He was very specific about how everything was laid out and the timing of things and very, very exact about detail. I know actors who’ve been in films. They’re filming a scene and they don’t necessarily know what the whole picture is, what the context is, or even what it might be about sometimes. But David is like a very careful film director.”

For Rattle That Lock, Manzanera maintains he went through “200 of these little bits and pieces of scraps and things… on [Gilmour’s] MiniDiscs and MeMO Pads, and little devices. Then we sat down and listened to 30 in the end. This was all going on until January. Then I said, ‘Let’s just work on 10 and see where it gets us. If we need anything else let’s pick from our pool of stuff, but let’s look at these 10.’ This whole process – especially working on the Floyd album too – got him stuck in. There’s an energy that wasn’t there when we started doing On An Island. It’s strange isn’t it? We’re 10 years on, and it’s a lot more energetic.”

“In some ways, I think I’ve found my feet,” says Gilmour. “It’s quite late in life to start finding one’s feet, I must admit. Or at least, to find them again.