Just recently, Grönland Records reissued two collaborative albums by David Sylvian and Holger Czukay - Plight & Premonition and Flux & Mutability. Touchstones in the evolution of ambient music, they rank among the very best of Sylvian's output. I was fortunate to interview Sylvian - via email only,...

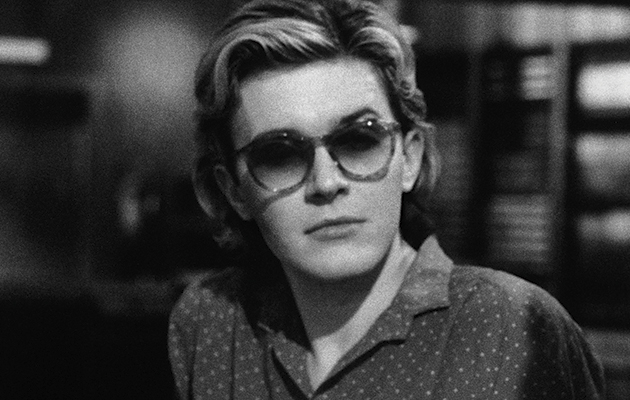

Just recently, Grönland Records reissued two collaborative albums by David Sylvian and Holger Czukay – Plight & Premonition and Flux & Mutability. Touchstones in the evolution of ambient music, they rank among the very best of Sylvian’s output. I was fortunate to interview Sylvian – via email only, sadly – for the latest issue of Uncut. Alas, there wasn’t room in the magazine to print the interview with David in full – so here’s the full transcript. Enjoy!

Follow me on Twitter @MichaelBonner

Secrets Of The Beehive was released in 1987: did you have any specific idea where you wanted to head next, creatively?

Plight and Premonition was recorded prior to Secrets Of The Beehive. It’s not indicative of a planned personal or musical evolution, instead it was born out of my friendship with Holger which had to have been reliant upon love, shared interests, goals, ambitions, and mutual respect. We got an immense amount of pleasure sharing in one another’s company so I’m inclined to place the emphasis on the ease of our relationship and where that happened to collectively lead us.

Holger was evidently impressed with you; but what impressed you about him?

With Movies he’d created a genre defying classic album that continues to impress even when listened to today. It’s an incredibly innovative piece of work. We spent a good deal of time together in the ‘80s, prior to my moving to the States. He was an incredible raconteur with an endearing sense of humour. It’s virtually impossible to think of Holger without a smile on his face. In his earlier incarnation as a member of the band Can, he tends to appear quite intense in group photographs, but he went through a radical change on leaving the band. He claimed he suffered a minor nervous breakdown and the story of his recovery is a rather remarkable one in which it’s impossible to discriminate between fact and fiction, reality and altered states. When he emerged from this experience he claimed to have discovered his sense of humour, which is very much to the fore in albums such as ‘Movies’. One of the very few musicians who could incorporate humour into the fabric of an album without diminishing the powerfully groundbreaking quality of the work (Hassell claimed humour in music was comparable to the same in sex, which may possibly say more about Jon than anything else, but you can see what he was getting at). In his role as composer, producer, musician, and engineer he was a genuine innovator. To work with him, or to witness him at work, was to see an entirely different methodology utilized than the kind you’d likely find as standard in professional recording facilities of the time. Now that a good deal of recording takes place outside of such institutions it’s possible there’s more room for personal innovation than there once appeared. But judging by the limitations of the technology touted by the recording industry, harping on about authentic recreations of technology of the past, I can’t be certain. Holger’s was a uniquely inventive mindset, beyond replication.

Get Uncut delivered to your door – click here to find out more!

How did the collaborative process work in the studio?

On this particular project: At Holger’s request, we’d convened at Can Studios with the intention of my recording a vocal for a track on what was to become Holger’s album Rome remains Rome. It was late in the evening and we were just talking, prepping for the work which was to be started the following day. Along the left and right sides of the studio, a variety of instruments were lined up. Towards the back was a grand piano and behind that, at the very back of the room, Jaki’s set up. I’d always loved the sound of pump organs but had never had the opportunity to play one. Here one sat towards the back of the room. I quietly seated myself and started up a drone of sorts, letting the bellows breathe, an asthmatic wheezing of tones which appealed to my ear. After a short while I heard various orchestral samples being pumped through a fold back system I hadn’t taken stock of, dotted around the open central space of the studio. I fell into a trance-like state as I played along with the etherial sounds which looped over and over, resounding around the room. After awhile I got up and moved to the piano. I dabbled, looking for a pattern to complement the loops, I played for 10-15mins or so before I found what I was looking for when Holger announced “That’s enough David, move onto something else.” It was then I realised that the analogue multitrack was in record. Until that moment I’d no idea this impromptu performance being documented. Holger had cut me short the moment he’d heard me begin to ‘compose’ a line. He’d only wanted the process, the uncertainty, the ambiguity of the searching out of ideas. And so the night went on. I’d pick up an instrument and play until a figure began to emerge and then the machines would be taken out of record mode. The basis for P&P was created in this manner. With Flux And Mutability a different approach was taken. It’s not possible, nor desirable, to repeat a particular process in the hope of achieving similar results so there was never a method of working together than we adhered to.

Flux & Mutability featured contributions from Jaki Liebezeit and Michael Karoli. Tell us a little about witnessing first hand (most of) Can at work in their natural habitat, Can Studios?

If I were to answer this as I imagine Robert Fripp might, I’d say the experience was a mixture of exhilaration, frustration, dedication, and hard work. In other words, a typical day in the life of a musician.

The titles of both albums are complimentary to one another. Did you and Holger always envisage there being two parts to this project?

We’d not even planned the first. P&P came about spontaneously while we were hanging out at Can Studios.

You’re evidently very proud of these records. What qualities most stand out to you now?

Proud isn’t a word I’d ever use to describe my feelings about any of the work I’ve produced. It either does its job or it falls short, if very fortunate, by a small margin, at others, by a long mile. Plight And Premonition doesn’t fall too short. We’d happened upon a form of composition that gave the impression that the sounds had been created while we were absent by instruments abandoned to the earth and the woods, sounded by the coarse winter elements. Or, the unanticipated impression on listening back to the work was that there was no one person dictating the direction of the pieces, as if the sounds on tape were created by the ghosts of the instruments themselves.

Was there anything you learned or developed with Holger – different working practices, fresh perspectives – that you took with you into your next project, Rain Tree Crow?

Simply put, improvisation became part of my compositional toolkit and it’s played and increasingly important part in my work as time’s gone on particularly, but not exclusively so, on projects such as Blemish and Manafon.

How much did your work with Holger go on to influence your own solo career?

Difficult to say. I’d already begun to embrace improvisation, prior to fully collaborating with Holger, on a project entitled Steel Cathedrals. As we move through life we absorb all manner of ‘influences’ from a variety of people, unexpected sources. Sometimes it’s easier for those standing on the outside to discern what influences might’ve been drawn upon and from where. For the individual creating the material all has been well digested to the point that, whatever the impetus for a project might’ve been, the innumerable influences have been so thoroughly absorbed as to become part of one’s own vocabulary.

Is there a thread that links your collaborators like Holger, your brother, Ryuichi Sakamoto, Robert Fripp and many more?

Not that I can think of. At best it’s a question of personal chemistry, shared goals, and suitably compatible aesthetics. Frequently, I simply have something I need to put down or explore in some form or another and I seek out the most appropriate ‘voices’ for the job. Putting together a unique constellation of ‘voices’ for any given session or project is part of the creative freedom, the thrill of what it is I’ve been able to do in my work.

Dead Bees On A Cake enjoyed a welcome Record Store Day vinyl edition. But what other projects – new or archival, musical or otherwise – are you currently working on?

I’m not currently thinking about a future in the arts. To quote Sarah Kendzior from her book The View From Flyover Country, “In an article for Slate, Jessica Olien debunks the myth that originality and inventiveness are valued in U.S. society: “‘This is the thing about creativity that is rarely acknowledged: Most people don’t actually like it.’”