On April 19, 1971, Gil Scott-Heron and Brian Jackson were still essentially students in “ratty jeans”, being suspiciously eyeballed by the seasoned jazz and soul vets who had gathered to record their first album of proper songs at RCA Studios in New York City. On bass was Ron Carter of Miles Dav...

On April 19, 1971, Gil Scott-Heron and Brian Jackson were still essentially students in “ratty jeans”, being suspiciously eyeballed by the seasoned jazz and soul vets who had gathered to record their first album of proper songs at RCA Studios in New York City. On bass was Ron Carter of Miles Davis’s second great quintet; on drums was Aretha Franklin’s musical director Bernard “Pretty” Purdie; on flute, established bandleader Hubert Laws; and conducting them all was The Impressions’ arranger, Johnny Pate.

“Terrifying, that’s the best way I can describe it,” says Brian Jackson today. “I was like, ‘Wait a minute – who am I, what am I doing here?’ I hadn’t even turned 19 and here are some of my biggest heroes all assembled in one place to play the music that I wrote. I remember Ron Carter having a little joke with me, questioning me about one of the chord changes. I was so intimidated that I said, ‘Well, what do you think it should be?’ And he was like, ‘No, man, I’m just kidding ya!’ and they all laughed at me. Which broke the ice. More than that, it demonstrated to them that we knew what we wanted.”

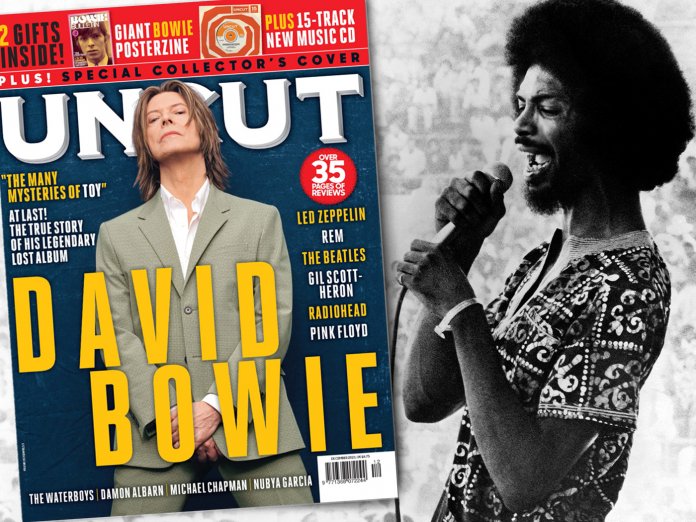

And when Gil Scott-Heron opened his mouth, everyone listened. His was not a classic soul voice; instead you were struck by the offbeat phrasing, wise tone and lyrical concision, something akin to a black Bob Dylan – a man with his finger on the pulse of a jittery and divided but still optimistic nation. Saxophonist Carl Cornwell, who used to jam with Scott-Heron in the practice rooms at Lincoln University before joining his backing band later in the 1970s, says that his vocal style was always unconventional. “When ‘Winter In America’ came out, we would always joke about how it was such a great song but he still couldn’t sing! But with the message he was delivering, it really didn’t matter. He wasn’t trying to be Bill Withers, he was trying to be a messenger.”

Pieces Of A Man flew out of the traps with the unforgettable wake-up call of The Revolution Will Not Be Televised. But Scott-Heron also tackled the plight of the junkie

and the laid-off factory worker with hitherto unmatched empathy. Unafraid to point the finger directly at the white establishment, he also came armed with practical solutions for those at the sharp end: Lady Day And John Coltrane offered music as a balm for depression, while When You Are Who You Are was a rousing self-empowerment anthem.

Released in the slipstream of Marvin Gaye’s What’s Going On, Pieces Of A Man’s soulful street-level sermons were more specific, and have arguably proved to be more influential, with trailblazing rappers Chuck D and KRS-One directly citing Gil Scott-Heron as the founding father of hip-hop. When his fellow musical firebrands tired of the fight in the mid-’70s, Scott-Heron kept fearlessly hitting bigger and uglier targets: Watergate, apartheid, nuclear weapons.