When Sergio Sayeg showed up in Joel Stones’ Tropicália in Furs record shop around 2007, it seemed like a fluke. Stones had seen the angular young man with a big cloud of dark hair around Manhattan’s East Village for weeks. But the stranger’s interest in the Brazilian-specific vinyl haven quickly revealed itself as soon as he started speaking, his English rounded with the distinctive full-bodied lilt of a Brazilian accent. The teenage Sayeg became a regular in the store, absorbing its contents – songs, discographies, track lists, liner notes, credits – like a sponge. Stones’ record shop would turn out to be a gravitational force for Sayeg, who’s now on his second Tropicália-indebted album under the name Sessa. His time there as a clerk and a customer changed his relationship with music forever, giving him a portal that hurtled him into the rest of his life.

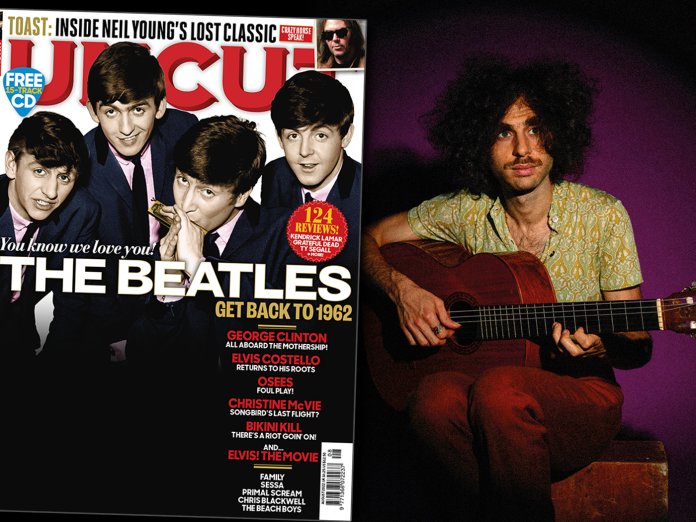

“You soak in, like, what’s a song? When do the drums come in? How should they sound?” Sayeg recalls, pulling apart a sweet, puffy brioche croissant in the sunny front window of a small Portuguese café in Jersey City. On stage and off, Sayeg dresses himself in striking vintage clothes that vaguely recall the 1960s-era psychedelia that seeps into his music. Though Stones calls Sayeg “a little Bob Dylan”, the mysterious Minnesotan would never be seen in such bold attire. Bob’s loss, really.

Fifteen years after he first stepped into Stones’ shop, Sayeg is nearing the end of a United States tour opening for the freewheeling Turkish psych-folk band Altin Gün. At the Music Hall of Williamsburg the night before we meet – the second of two sold-out shows there – the 33-year-old sat hunched over his honey-coloured acoustic guitar on a late April evening. He introduced songs from his second album, Estrela Acesa, carrying a soothing, radiant energy. The project’s title, in Portuguese, means “burning star”.

Sayeg made the record at the home studio of his São Paulo friend Biel Basile on Ilhabela – “beautiful island” – located about 200km southeast of São Paulo. There, the pair built the album’s rhythmic foundation from a beachside locale. But Sayeg’s journey toward being an ascendant steward of one of Brazil’s beloved musical exports began well before he ever stepped across the threshold of an enticingly named record store with a guitar in the window.

Now 33, Sayeg doesn’t remember when or where he came by the nickname Sessa. He uses the title as a mononym for a full band, where he’s joined by singers and a drummer. Sayeg grew up in the very small enclave of São Paulo’s Sephardic Jewish community. “I don’t think people that attend synagogue would say, ‘Oh, this is a music place,’” Sayeg recalls. “It is very musical. But it’s just chance.”