How a righteous funk anthem and future block party staple was birthed in a Brixton basement. “The bass was the genesis…” in the latest issue of Uncut magazine – in UK shops from Thursday, December 8 and available to buy from our online store.

A key scene in new documentary Getting It Back: The Story Of Cymande shows how DJ Jazzy Jay used to cut between two turntables to extend the exuberant breakdown of “Bra”, sending a Bronx block party into raptures. It’s no surprise that the track became a foundation stone of hip-hop, sampled by Sugarhill Gang, Gang Starr and De La Soul, as well as on Raze’s early house hit “Jack The Groove”.

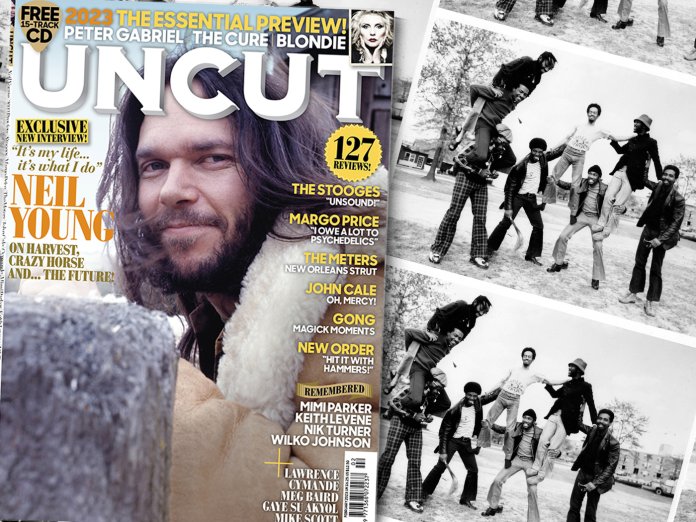

So who were the impossibly funky crew behind it? Surely they were from Harlem or New Orleans? Or maybe Kingston or Lagos? Nope. “Bra”’s co-writers Patrick Patterson and Steve Scipio grew up on the same street in Balham, south London, after their families emigrated to the UK from Guyana when they were kids. Coming of age in the late ’60s, they envisioned a band that would capture the spirit of the times – black pride, peace and love – while celebrating their Caribbean heritage. Their name came from a popular calypso about “a dove and pigeon fighting over a piece of pepper” – Cymande was the dove – and they recruited band members from south London’s Caribbean diaspora.

With lyrics that encouraged its listeners not to abandon the struggle (“But it’s alright / We can still go on”) “Bra” made a decent splash on its US release in 1973, following Cymande’s debut single “The Message” into the R&B charts and winning the band a support tour with Al Green. But back in the UK, the glass ceiling descended. Dispirited with the lack of opportunities for black British groups, Cymande disbanded in late 1974. Patterson and Scipio eventually both studied law, going on to take up important positions in the governments of various Caribbean nations. As such, they were oblivious to Cymande’s second life as hip-hop progenitors. But word eventually reached them of their popularity amongst a new generation of crate-diggers, and Cymande reformed to jubilant scenes in 2014 with most of their original lineup intact. A new album is currently in the works, to follow the reissue of their original three albums.

“I had no idea,” says drummer Sam Kelly of Cymande’s miraculous rebirth. “One of the things that blows my mind is that we played in Brazil, we went to Croatia, all these places. My partner and I went to Australia a couple of years ago – we’d go out to a restaurant and hear our music being played in Melbourne, 12,000 miles away. It still puts a shiver down my spine.”

PATTERSON: I came to London in 1958, Steve came in ’63. And since then we’ve been together. Our street was full of people, many of whom came from our country, and we were all in the same community. So we carried our Caribbean culture with us. [In the late ’60s] we had a jazz group called Metre, which was the genesis of Cymande. We used to do Miles Davis’ “Footprints”, Rahsaan Roland Kirk, things like that. We liked to play in different time signatures. Looking back on it now, we were very inventive.

SCIPIO: For seven or eight months before we started to put Cymande together, we also played with a Nigerian band called Ginger Johnson And His African Drummers. Ginger was a well-known performer, he played with The Rolling Stones at Hyde Park.

PATTERSON: All of it contributed to where we were as musicians, directing us towards our future musical style.

KELLY: We started in the basement of my family house on Crawshay Road in Brixton. The main thing they emphasised is that, come hell or high water, they wanted to do original material. I wasn’t playing an instrument at all before I joined Cymande, but I used to listen to everything from James Brown to Hendrix, Sam & Dave to Pink Floyd.

I was a blank canvas – I didn’t want to sound like any other drummer. The person that had the most influence on my playing was Steve. He didn’t play bass rhythmically, he played it lyrically. I was just trying to complement what he was playing.

PICK UP THE NEW ISSUE OF UNCUT TO READ THE FULL STORY