“We basically started around the same time, right?” says Jeff Tweedy, musing on the shared history between Uncut and Wilco. “I remember buying Uncut when we would tour Europe, it was easier to get them there then. It was pretty exciting to see a magazine that in-depth about music on a newsstan...

“We basically started around the same time, right?” says Jeff Tweedy, musing on the shared history between Uncut and Wilco. “I remember buying Uncut when we would tour Europe, it was easier to get them there then. It was pretty exciting to see a magazine that in-depth about music on a newsstand at the airport. But we get it here at The Loft now – I probably haven’t missed many issues over the years.”

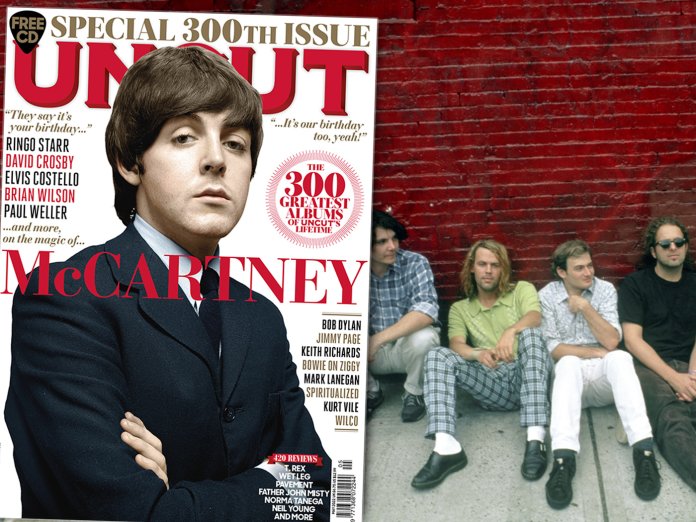

With five Wilco releases included in the 300 greatest albums of Uncut’s lifetime – the most of any artist – it seems a fine time to run through all of the band’s work with their restless leader, from 1995’s AM to 2019’s Ode To Joy. Tweedy even drops some hints about the band’s next opus along the way.

“When things sound confident, I get nervous,” he explains of one thread running through his life’s pursuit, “because it doesn’t work for me emotionally when things are super-confident. I still crave a brokenness to whatever it is we’re doing. And a lot of the time, it’s me providing that – my voice is a fairly broken vessel for whatever I’m singing.

“You know, all rock music is stupid. But to me it has the potential to be sublime in ways that almost nothing else does.”

AM

(1995, Sire/Reprise)

Tweedy and the remains of Uncle Tupelo rush out their power-pop debut

TWEEDY: The ultimate dream for me was to be in a band that toured in a van and played shows and got to go around and see places – so I’ve outlived my life goals by about 30 years! I didn’t want to take any time to sit around and think about what I wanted to do [after Uncle Tupelo split], I just wanted to do it, to get back in the van with somebody and go play shows. We mapped out the songs we wanted to record within a few months of Uncle Tupelo’s last show – I probably was fearful that if the momentum stopped, I wouldn’t get to do this thing I love.

All our records sound a little bit different to each other, but this one really stands out. I think maybe power-pop was a potential direction, coming out of Uncle Tupelo, that I thought I might have the songwriting style for – because I liked a lot of ’60s melodic stuff. On “Box Full Of Letters” or “I Must Be High”, I was maybe thinking more about the Big Star end of my record collection. Song for song, AM holds up for me.

There are a few songs that feel fairly half-baked, like they could have either stood to be B-sides or outtakes, but a lot of my favourite records have songs like that. I still enjoy hearing it, it doesn’t sound completely dated, because it doesn’t really sound like anything being made at that time. It wasn’t going for a grunge thing or a contemporary sound really. Luckily, there aren’t many records in the Wilco catalogue that have those markings of a specific period of recording, I don’t think, this one included. It sounds delightfully out of step.

BEING THERE

(1996, Reprise)

Recorded in fits and starts around the US, this epic double album took Wilco into weirder territory

[Tweedy’s son] Spencer was born during the promotion period of AM, and smoking weed just didn’t fit into my ability to cope with the stress of fatherhood. It just made everything worse [so I quit]. But my mind was being expanded by the possibilities [of music] that I’d always maybe pushed aside because I wanted to make things that fitted into an environment that had been built around Jay Farrar songs in Uncle Tupelo. I had always been a very curious listener, and interested in a lot of different types of music, experimental music and things like that.

My main passion was not just country or folk, it was records, and being excited by sound. So Being There explodes into more of that. Music has its own psychedelic and transfomative qualities that far exceed the possibilities of drugs in my opinion. To me, the world is pretty fucking psychedelic. We recorded in a lot of different places: there are tracks from Portland, Nashville, Missouri, Atlanta, which was The Black Crowes’ rehearsal space. We were just going anywhere we could get a day booked on our tour, because that was another part of my dream, that we could be a band like The Rolling Stones and have a mobile recording truck.

We couldn’t afford that, but we could record in a friend’s studio if we made friends that had studios. Sometimes we would get more than one thing [in a day], but generally we were just focusing on one song. On “Misunderstood”, we had fun playing each other’s instruments; but, on a deeper level, I don’t think it was an accident that it ended up being the final take, because it was a way to get at something that I felt the song was trying to express. What felt emotional to me was trying to fight through something stupid – it’s just two chords, it’s so stupid.