The more-than-extensive ‘Immersion’ edition of Pink Floyd’s opus The Wall (the box includes a scarf and marbles!) is reviewed in our latest issue, out now – so we thought we’d revisit John Lewis’ excellent feature from June 2011 (Take 169). As the extravaganza arrives in Europe, Uncut me...

The more-than-extensive ‘Immersion’ edition of Pink Floyd’s opus The Wall (the box includes a scarf and marbles!) is reviewed in our latest issue, out now – so we thought we’d revisit John Lewis’ excellent feature from June 2011 (Take 169). As the extravaganza arrives in Europe, Uncut meets the obsessive fans, stoners, bloggers and military advisors who’ll follow Waters and his lavish production to the ends of the globe…

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

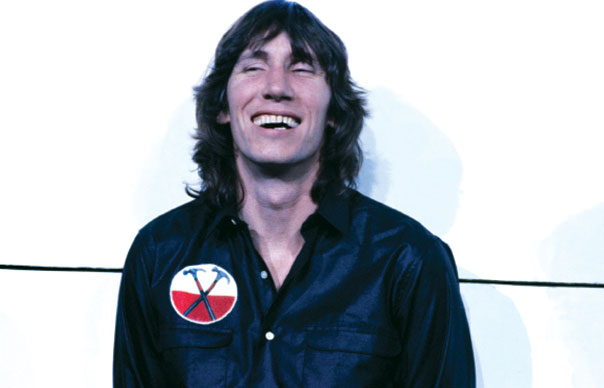

Kevin, 59, from Norfolk, is a Pink Floyd fan who has, as he puts it, “been mad for years. Fucking years”. In 1994, Kevin separated from his wife and children, the construction firm he owned went bust and he suffered a minor breakdown. “I lost everything,” he explains. “All I had left was Pink Floyd.” With £500 in his pocket, he decided to fly out to Portugal to see the band start their Division Bell tour. “I didn’t have any gig tickets or anywhere to stay,” he continues. “The idea was to find a tout, maybe see a couple of shows and come home. I ended up spending the next four months watching all 52 dates on that tour.” Kevin scrimped on budget flights and hotels. He’d inter-rail, cadge lifts, sleep in airports and on friends’ couches. He has seen almost every Pink Floyd, Roger Waters or Dave Gilmour show since, following his idols from Lisbon to Moscow, acquiring an encyclopaedic knowledge of Europe’s budget hotels and public transport links – not to mention each city’s touts, bootleggers and drug dealers.

We’re in a Milan bar on April 1, just hours before Roger Waters takes the stage at the 12,000-capacity Mediolanum Forum to perform The Wall in its entirety. Waters began touring The Wall in Toronto last September, playing a further 55 shows in North America; tonight is the seventh of 60 European dates, that include five nights at London’s O2 Arena this month. In total, Waters will play to nearly two and a half million people. And Kevin? He’s going to every single concert.

In his Wall-themed baseball hat, Kevin has become a cult figure on the Pink Floyd circuit. Other Floyd fans talk of him in hushed tones. They queue up to have their picture taken with him. Outside gigs, they shout his name, giving the ‘crossed arm’ salute from The Wall. Kevin grins and salutes them back.

“I don’t have a house, a car or a job,” says Kevin, now a grandfather of three. “I stay with friends around the world who are Floyd fans. They’re my extended family. I basically make money as a bootlegger – I sell posters and T-shirts at gigs and make just enough money to keep going. I’ll always turn up to every show with 30 Euros in my pocket.

“I have a thing about never meeting Roger,” Kevin continues. “I know he knows who I am. I know he looks out for me at every gig. But I don’t think I’d want to meet him. I used to be mad keen on Mike Oldfield. Then one day I met him, said ‘hello’ and he replied: ‘Who the fuck are you?’ No, don’t laugh! It was heartbreaking. Put me right off him. I’d rather keep my distance.”

He is by no means alone in his Floyd obsession. I meet Simon, a 43-year-old from Huddersfield, who has been to 171 Roger Waters and David Gilmour gigs since 2000. I meet Anders and Johan, two 49-year-old public transport employees from Sweden, who’ll visit Chicago, Toronto, Milan, Rome, Copenhagen and Stockholm on this tour. There is Jens, a 44-year-old from Copenhagen, who took out a 20,000 Euro loan for a new kitchen in 2002, before deciding to blow it all to follow Waters on tour.

Of course, Pink Floyd aren’t the only band to attract super fans (“you should meet the Status Quo ones – now they really are mental,” grins Kevin). But there’s a spiritual intensity that marks them out from the rest, as they talk about a Damascene conversion from “pop pap” to the true cause of the Floyd.

For Mark, a 60-year-old from Vermont, it was hearing Meddle at a student party in 1972. For Henrik, a 36-year-old from Cologne, it was finding a VHS copy of The Wall film in a charity shop; for Marti, a Catalan Alexei Sayle lookalike, aged 40, it was watching Live In Pompeii on late-night TV. Although we’re talking about a band who’ve sold 250 million records, each regard Pink Floyd as their own discovery, their own secret.

Talking to some of the 50,000 people at Barcelona’s Palau Sant Jordi on March 30 and in Milan two nights later, I meet a smattering of studious soixante-huitards and ageing stoners. But the audience appear much younger, and less overwhelmingly male, than you’d think. Indeed, it’s probable that Waters, 68 this year, is at least double the median age of his audience.

“In North America the audience is noticeably older,” notes blogger Simon Wimpenny, who’s seen every American and Canadian date on this tour, and will follow it around Europe. “Stateside Floyd fans are mainly Dark Side Of The Moon-loving stoners in their fifties. In continental Europe, it’s the exact opposite.”

Given that this tour will play 115 sold-out dates in 20,000-to-25,000-seater arenas, what’s the appeal? It’s a gloomy album, designed for teenage misanthropes, isn’t it? “We toured our version of The Wall for more than a year,” says Jason Sawford from the Australian Pink Floyd Show, the world’s biggest Floyd tribute band. “Bloody depressing it was, too. Couldn’t wait to finish that tour.”

But even a lapsed Wall fan like me will concede that this production is a staggering live event, more like a Wagner opera or a military tattoo than a rock gig. The set – a 35-feet-tall, 240-feet-wide wall of cardboard bricks erected in front of the band during the show, then collapsed at the end – remains from the original 1980-81 tour and the 1990 revival. But there’s been a quantum leap in stagecraft since then. Now there are pyrotechnics, stormtroopers, a choir of schoolchildren, a cast of giant Gerald Scarfe puppets and a rolling barrage of sound effects. Most impressive of all are the complex, detailed and constantly mutating animated projections. Some are based on Scarfe’s iconic animations – but there’s also Banksy-style graffiti art, Wikileaks footage, allusions to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and agitprop anti-war sloganeering. Some have objected to the way Waters has continued to retool his psycho-drama as a parable for the Berlin Wall, the West Bank barrier, and the fight against global totalitarianism. “I don’t have a problem with that,” explains Jakub, 33, a Czech student at the Milan show. “This is a show and a message that resonates around Eastern Europe.”

“It makes more sense now, post 9/11, post-Iraq, than it did when I first saw it in Germany, 1981,” adds Thomas from Denmark. “He has taken this adolescent howl of despair and made it universal.” Near the start of the show, the opening bars of “The Thin Ice” are accompanied by the projection of a single photo of Waters’ father, alongside the details: “Lieutenant Eric Waters, born 1913, Co. Durham, England; died 1944, Anzio, Italy”. There follows a list of those killed in conflicts since World War II. While it receives applause in Europe, such political grandstanding attracted boos and walkouts during the American dates. I wonder what Mark Gunzinger, a US military advisor and Republican who has travelled from Washington DC to see the show, makes of it.

“You know what? I’ve fought in wars. I’m good at war. But I hate war. I share that with Roger. I think a lot of people on the American right are pretty anti-interventionist. We’d rather not be in Iraq or Afghanistan or Libya. We have more in common with Roger and the anti-war brigade than you might think.”

The elephant in the arena is David Gilmour. Waters has announced that his old sparring-partner will join the tour as a guest at one show, which only emphasises his absence from the proceedings. Waters requires not one but three musicians (singer Robbie Wyckoff and guitarists Snowy White and Dave Kilminster) to replace him, while Gilmour’s co-writes “Run Like Hell”, “Young Lust” and mobiles-in-the-air anthem “Comfortably Numb” attract the most ecstatic responses.

Trawl the Pink Floyd message boards and blogs, and it’s clear that Gilmour is the more popular Floyd man. During a Gilmour show at the Royal Festival Hall a few years ago, an audience member shouted, “Where’s Roger?” Gilmour’s response – “Who gives a fuck?” – got the biggest cheer of the night.

“Roger is a bit of a – how you say? – prick,” says Marco from Barcelona. “In the same way that Mick Jagger is a prick. Dave, like Keith Richards, is the cool guy. We love Dave unconditionally. We love Roger more reluctantly. But you cannot deny that it is his show.”

After the disintegration of the band in the early ’80s, Waters was regarded by some hardcore fans with the same vitriol that Labour Party activists once reserved for David Owen. This situation was only amplified when the post-Waters Floyd albums (The Division Bell, A Momentary Lapse Of Reason) conspicuously outsold their old leader’s efforts, Radio KAOS and Amused To Death. However, among many obsessives, this has changed. Following his 2006-8 Dark Side Of The Moon tour, and this recreation of The Wall, Waters appears to have clawed the Pink Floyd brand back from his former band mates in all but name.

“Gilmour might be a nice guy but he’s a miserable sod on stage,” says blogger Simon. “You don’t get anything back from him, there’s no charisma, just a guy staring at his guitar strings. Whatever you think of Roger, he knows how to put on a show.”

That wasn’t always the case. During the performance of “Mother”, where Waters duets with a 1980 film of himself playing the song, he tells the audience “to have some sympathy for the younger, sadder, fucked-up Roger from 30 years ago”. The gloomy frontman who’d spit on hecklers, slag off arena rock tours and chastise his fans for having the audacity to enjoy themselves is no more. Nowadays, despite multi-tasking as a paranoid rock star, fascist dictator and judge throughout the course of the show, Waters frequently jumps out of character to wave and smile and salute the audience, as if suddenly aware of a rock star’s responsibilities.

None of this explains why these superfans want to see the show twice, let alone 50 times. Is it an obsessive compulsive disorder? A desire to relive their youth? To recapture the spiritual awakening when they first heard the band? “I think a lot of people would like to do what I’m doing,” says Kevin, slightly baffled. “I’m just lucky that I’ve found a way of doing it. It’s a great show. The moment it’s finished I want to see it all over again. I can’t wait.”

I watch Kevin as the show reaches its climax. He is punching the air and singing along to every word. He has already seen this production half a dozen times, and watched the movie “more than a thousand times”. But, as he warns me before the gig, he still gets emotional every time he hears this music.

During “In The Flesh” he is dutifully doing fascist salutes; on “Run Like Hell” he plays air drums, by “Bring The Boys Back Home” he has tears rolling down his cheeks.

By the time the wall collapses and the band emerge from the rubble, in civvies – with accordions, banjos, mandolins and a trumpet – to perform an unplugged “Outside The Wall”, Kevin has his head in his hands, his big shoulders heaving up and down. Tomorrow, he’ll be doing exactly the same thing again.