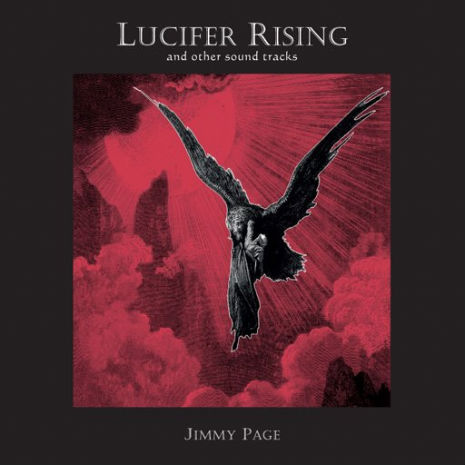

On March 20, the spring equinox, Jimmy Page finally made available his soundtrack to “Lucifer Rising”, at least to order, on vinyl. There would, he announced, be a special run of 418 numbered copies, with the first 93 copies signed and numbered. The figures were auspicious: 418 is the kabbali...

On March 20, the spring equinox, Jimmy Page finally made available his soundtrack to “Lucifer Rising”, at least to order, on vinyl.

There would, he announced, be a special run of 418 numbered copies, with the first 93 copies signed and numbered. The figures were auspicious: 418 is the kabbalistic number for the magic word “Abrahadabra”, according to Aleister Crowley; 93 is the kabbalistic sum of the Greek words for “love” and “will” – Crowley’s shorthand for “Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the Law.”

For those who have spent at least part of the last 40 years looking for black magical significance in everything Jimmy Page has done, the whole event was – though this may not be strictly the right word – a Godsend. This week, the vinyl copies of “Lucifer Rising” finally arrived, with fascinating sleevenotes by Page himself. He talks about how he became involved with creating a soundtrack to Kenneth Anger’s movie, having been “experimenting with the theatre of the avant-garde”, and contextualises it as part of a long-term “interest in underground everything” dating as far back as the Yardbirds’ “Glimpses”. “The fact that I got involved with Kenneth Anger and Lucifer Rising,” Page concludes, “was really just a step along the road of my interest in the extreme and alternative.”

Listening to these unusual and compelling recordings now, one of the many questions which arise is why Page has released so little music in the past three decades, and why this enduring avant-garde interest has manifested itself so rarely in public. “Lucifer Rising” features six tracks over two sides of vinyl, with the first side entirely taken up by “Lucifer Rising – Main Track”; a quite superb ritual piece that begins, as Page notes, with “a bass tanpura that provides a majestic drone”.

Slowly and methodically, after about five minutes Page starts thickening out the sound, with some murky chanting of uncertain origin, and a bowed guitar sound that is as close to giving Led Zeppelin diehards a lifeline as anything on this uncompromising set. Forlorn waves of Mellotron, on what sounds like the flute setting, give way to a fat and abrasive ARP synthesiser line, with discordant bass frequencies. The overall effect is much more than arresting than notional ideas of soundtrack music would suggest, and nearer in spirit to, perhaps, Lamonte Young, Terry Riley, John Carpenter and Sunn O))) than to blues-rock.

After about 14 minutes, there is a booming flutter of tablas, and the whole processional steps up a notch, with strummed acoustic guitar in there, too. The ARP “provided the Horns of Jericho,” writes Page. It would be easy to write about all this in the context of satanic practice, grim transgressive acts and so on, but happily “Lucifer Rising” works just fine as music above and beyond the somewhat gothic signifiers.

Side Two comprises of five shorter tracks, culminating in a reprise of the main theme called, in self-explanatory fashion, “Lucifer Rising – Percussive Return”. “Incubus” is a scrabbling treated guitar piece that sounds a lot more like Derek Bailey than what we traditionally expect of Page. “Damask” has a similar restless nature, but this time with a bowed guitar and an Indian bent explained by the scholarly Page as “a simple homage to the sarangi”. A second “Damask – Ambient” follows later (after “Unharmonics”, where comparable bowed atmospherics are leavened by “the naked solo guitar [that] moves cautiously through a sonic landscape”), with – and I should again defer to Page’s own descriptive skills – “a more dense, heavily perfumed ambience”.

It’d be pretty ignorant to claim that the contents of “Lucifer Rising And Other Sound Tracks” are utterly without parallel in Page’s work. Part of the overwhelming richness of Led Zeppelin’s music stemmed from the diverse and esoteric influences that Page brought to arcane blues structures, and you can certainly find obvious precursors of this music as far back as, say, the breakdown to “Dazed And Confused”. Nevertheless, for those whose stereotype of Page is a little more triumphalist and a little less exploratory, this might be an unexpected and rewarding way into his “extreme and alternative” world. If you’ve got a copy, let me know what you think.

Follow me on Twitter: www.twitter.com/JohnRMulvey