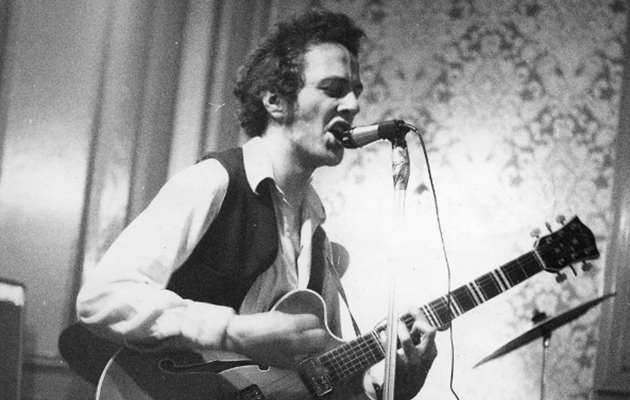

To mark what would have been Joe Strummer's 66th birthday today [August 21], here's a piece from Uncut's November 2014 issue [Take 210], where Allan Jones - an old friend of Strummer's from art school in Newport - chronicled the history of Strummer's pre-Clash band, the 101ers. For some incredible ...

Hastings, one night at the end of July 2014, storm clouds gathering, rain on its way. A pale coloured Porsche pulls out of the station car park, Clive Timperley at the wheel. The last time I saw Clive, who these days is a driving instructor here on the south coast, he was lead guitarist in The 101’ers, author of the firestorms over which Joe Strummer, especially in the band’s latter days, raged. We’re on our way to Clive’s rather swish pad in a converted Victorian school, where he now wonders how much he’ll be able to remember about the times I’ve asked him to talk about.

“It’s all a bit jumbled, frankly,” he says. “The early-70s were a bit of a mess. There were a lot of drugs.”

Not long after this, however, it’s 1971 and Clive is recalling the year he lived in Ash Grove, Palmer’s Green, sharing a house called Vomit Heights with a bunch of art students, one of whom is the young Johnny Mellor, who everybody already knows as Woody and in due course becomes Joe Strummer.

“Woody was a bit bonkers, as I recall, a bit off his head,” begins Clive. “But he was funny and even then he had this charisma, if you like. He’d come into a room, sit down and immediately there’d be people gathered around him. People wanted to talk to him. He was an interesting guy.”

Clive at the time is currently in a group called Anaconda, signed to Shel Talmy’s production company, for who they recorded an album, never released. He has no idea then that Woody is interested in music so after losing touch with him when he heads to South Wales, fetching up in Newport, Clive is surprised in September, 1974, to discover that Woody’s back in London and in a band who are making their debut at a pub called The Telegraph in Brixton, supporting Dennis Bovell’s Matumbi at a Chilean Solidarity Campaign benefit that on a whim he decides to go to.

The band he sees are billed as El Hauso And The 101 All Stars and their line-up that night is Woody on rhythm guitar, Simon “Big John” Cassell and Alvaro – El Hauso, himself – a refugee from Pinochet’s Chile on saxophones, Patrick Nother on bass and his brother Richard on drums, a last-minute stand-in for the band’s errant original drummer who he eventually replaces. He’s been playing drums exactly a week.

“I was just dragged into it,” Richard recalls from his home in Spain, where he’s lived in Granada since 1988, after a post 101’ers career that included stints with Bank Of Dresden, The Raincoats, Basement 5 and PiL (he’s the uncredited drummer on Metal Box). “Woody said, ‘Just keep the beat. It doesn’t matter if it gets faster just make sure it doesn’t slow down.”

“They were terrible,” Clive laughs. “Patrick played bass with his back to the audience, like Stuart Sutcliffe with The Beatles. He couldn’t play and was desperately nervous. They only seemed to know about four songs and they played them all at least twice. Big John was singing lead on most of them, but Woody did a couple of Chuck Berry numbers. I remember thinking they were rubbish.”

In January 1975, however, he sees them again, at a pub called The Chippenham, in Shirland Road, just off Elgin Avenue in west London, in an upstairs room the band have named The Charlie Pigdog Club.

“It was still pretty raw, most of them were still learning their instruments, they had speakers made out of kitchen cabinets and it was still a bit of a shambles,” he remembers. “Most of them were living in a squat at 101 Waterton Road, about five minutes from The Chip. It was all unbelievably basic.

“But they’d obviously been practising like maniacs. Woody was suddenly this mad guy with a light blue suit and a leg that was shaking uncontrollably. I was really impressed. I thought, ‘Blimey, he’s giving it a lot of energy, he’s fantastic.’ He didn’t know how to play the guitar but he had so much energy, it was amazing just watching him. Later, he became an absolutely relentless rhythm guitar player, to the point where he’d break strings, end up with bleeding fingers. The more blood there was on the guitar at the end of the night, the better the gig had usually been.”

Clive’s got his own band at this point, Foxton Flight – “an acoustic, Steely Dan-type thing” – but they aren’t really getting anywhere. He brings his guitar to a couple of 101’ers rehearsals, jams with them on some tunes and fits in well enough for Woody to take him aside one night. “He said, ‘I’ve had a word with the boys’ – those were his exact words – ‘and we’d like you to join the band.’ And I’m going, ‘Oh, so it is a proper band, then?’

“I mean,” he says, “at that point they were still pushing their gear around in a pram.”