As part of our Nick Cave cover story in the current issue of Uncut, I spoke to film maker John Hillcoat. Hillcoat and Cave’s friendship stretches back to Melbourne in the late 1970s, while their first professional collaboration came in 1981, when Hillcoat edited the promo video for The Birthday Party single, “Nick The Stripper”. Since Mick Harvey left the Bad Seeds, I’m pretty sure Hillcoat can now claim the dubious honour of being Cave’s longest-serving collaborator. Their work together includes the occasional Bad Seeds and Grinderman video, while Cave has also scored Hillcoat’s films To Have And To Hold (1996) and The Road (2009). But more substantially, Hillcoat has directed three of Cave’s screenplays: Ghosts… Of The Civil Dead (1988), The Proposition (2005) and, of course, Lawless. What was the appeal of the material? The book seemed very much to dovetail together a lot of our shared influences, going right back to when we first met. Flannery O’Connor, William Faulkner and Cormac McCarthy loomed large in our formative years. Nick just happened to be tapping into the same sort of music, when we were younger, of the blues and country and folk and rock. So all these forces and influences all came together in this one book. The world was really interesting. And that opened it up for the music as well. You’ve known Nick since the late 1970s. Can you give us a flavour of what Melbourne was like back then? Oh, it was wild. It was just like the film: lawless. Weirdly enough, our first really in depth working experience was on Ghosts… Of The Civil Dead. I was attacked and my jaw was broken in two places. My entire mouth was wired shut. So I was talking to him through clenched teeth and having liquefied meals through straws. Literally, that’s how we started working about the script, talking about high security prison and violence, having been a victim of violence. There was definitely an edge to Melbourne. It’s got a real underbelly. There used to be a lot of police corruption and there’s always been a huge influx of illegal drugs, and with police involvement. That was very much prevalent in our youth. I grew up in the late Sixties in New Haven, Connecticut. I’d seen police shoots out in front of my eyes, a car chase with the cops leaning out the window firing bullets which sounded more like a cap-gun or a pop-gun, very anti-climactic. But the thing that impacted on me as a youth were all the cultural upheavals, going on Martin Luther King’s funeral march, the repeated black and white TV showing Robert Kennedy’s assassination. In a very short time, all my parents heroes had perished and been assassinated violently, whether they were the president all the way down to rock stars. Can you tell us about the influence Michael Ondatjee’s Billy The Kid poems had on you and Nick. Weirdly enough, when I was in Canada I had that as a teenager. It was only on the University of Toronto press, he was just a local university writer. I was blown away by that mixture of documentary realism and poetic prose. It was so like the movies I was watching – Peckinpah, Scorsese, Arthur Penn’s Bonnie & Clyde, The Godfather. It had a huge impact on me and likewise Nick loved that book. It was a real galvanising force, the Ondatjee book during that era in the Seventies. It was a very vibrant time, I might add. Who else was on the Melbourne scene at the time? It was the Little Bands scene. It was that whole post punk period where it was like a cottage industry. All these people we knew who had their own record labels, and we all went to certain venues to see the concerts, so it was all self generating. Between the local, tiny record shops and record companies and the venues there was this circular thing, where everyone we knew were forming bands and being in bands and then watching bands and listening to music. There was Missing Link and Au Go Go and these labels that are long since gone, but they picked up on Nick’s band. There was a band called The Reels Nick and I featured the singer in Ghosts… Of The Civil Dead [Dave Mason]. They had offers from every major record company in the world, but they were ferociously uncompromising. There was a whole two fingers up at authority. We had tiny venues where The Clash, Iggy Pop, The Cure were all going through, like the Crystal Ballroom. I had the job of filming those shows, working in the venue doing a recording for their archive. And then Nick, when he went overseas, they really took up. How did Nick’s contributions for Ghosts… Of The Civil Dead come about? He was already clued up on the whole music/prison thing, and the blues – all these characters came from literature and secondary sources. Then myself and the co-writer who was also producing, Evan English, did a lot more real research where we went into the prisons, so we took it somewhere more grounded in realism. But Nick did create these very flamboyant characters, and one of them of course was this character who was tailor made for him. Nick was a bit wild at the time, and it just suited his particular state to let him go off. We even created this set – I’ll never forget – we just had a basic plan of this guy entering the unit and just being so obnoxious: he drew on some experience when he was in a lock up in New York, and we reference self-mutilating which was very popular in high security prisons. So he got all these aspects and then just ran with them, because he couldn’t… he was too of the frame of mind, he couldn’t learn lines and work in a traditional sense. So we just let him rip. Nick says his acting peaked with Maynard. Do you agree? Yeah, even the ex-inmates who’d done a lot of hard time were wary of Nick. Let’s just say, we got him at the right time and tailored it to the state that he was in. Maybe that a little bit exploitative, but he didn’t seem to mind. [laughs] It’s his acting triumph. I hear Russell Crowe was nearly cast in The Proposition. What happened there? He was a big fan of Nick’s, and he was very keen on getting involved. He was quite a star at the time and it was a difficult negotiation. We talked about him doing the Ray Winstone role, but then we all agreed that the Danny Huston role was the most appropriate. There were all sorts of logistics and other reasons… tight schedules, and all that. We actually had a different cast. At one stage, we even had Liam Neeson involved and Danny Huston was going to play Ray Winstone’s role. It was a lot of moving pieces. Guy [Pearce] was the first one in, and remained loyal throughout. It took us years, many years to get that off the ground. Nick is very much in charge in his music career. But in his film career, he’s more at the mercy of other, external factors – studios, budgets, schedules. Is that frustrating for him, or do you think he enjoys being part of something bigger than him? What he hates is the whole dance and the politics and the pressures. He’s got very little patience for it. We all hate that, but he in particular, because he’s so used to things getting done his way. But actually there is also the aspect of losing himself and being part of the process, a craftsman, a collaborator in a very real sense, that he enjoys. So it’s pros and cons. The negative is all the time delays and the financial pressures and the politics. But the way the collaboration works takes him away from being the frontman. What parallels do you see between Nick’s film and music careers? For me, it’s a real treat because there is an extra cohesion you don’t normally get. Because you start with a script and end with sound and music. But we talk about music at a very early stage, when he’s writing the script, which is an interesting way of approaching scores and soundtracks. And there is in his writing. What makes him such a great scriptwriter is he’s got an ear for dialogue and he’s got a kind of… I came to film making via editing, and editing is all about rhythms and pace and likewise with music. I think there is a rhythm, a musicality in his scripts, that is quite special and unique. We love collaborating together, and when I’ve directed his music videos, it’s nice for me to lose myself and just facilitate his requirements as the frontman. But it’s very different mediums though, with music projects and music videos, and that’s something else that Nick has great grasp of. What are your future plans with Nick? He’s worked on another script, from another scriptwriter, that he has rewritten for me, which is my next film. It’s very different. It’s a contemporary crime thriller, so far set in LA, that we’re casting. So that’s very different for Nick and I. It’s called Triple Nine. But there’s numerous things we’re talking about, and we’re no the lookout to find the next thing. We’re always, as soon as we finish one thing, we’re talking about the next. There’s several things on the horizon. Lawless is released in the UK on Friday

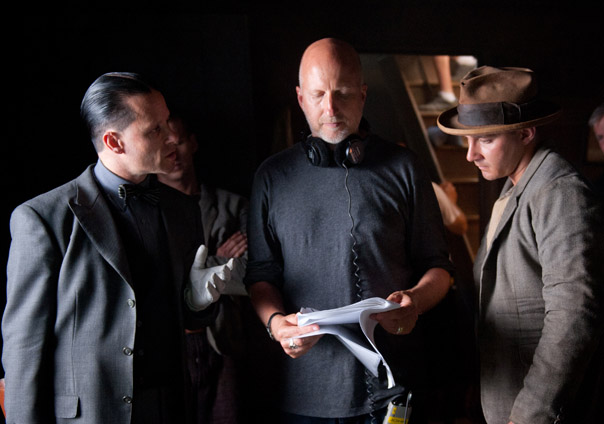

As part of our Nick Cave cover story in the current issue of Uncut, I spoke to film maker John Hillcoat. Hillcoat and Cave’s friendship stretches back to Melbourne in the late 1970s, while their first professional collaboration came in 1981, when Hillcoat edited the promo video for The Birthday Party single, “Nick The Stripper”.

Since Mick Harvey left the Bad Seeds, I’m pretty sure Hillcoat can now claim the dubious honour of being Cave’s longest-serving collaborator.

Their work together includes the occasional Bad Seeds and Grinderman video, while Cave has also scored Hillcoat’s films To Have And To Hold (1996) and The Road (2009). But more substantially, Hillcoat has directed three of Cave’s screenplays: Ghosts… Of The Civil Dead (1988), The Proposition (2005) and, of course, Lawless.

What was the appeal of the material?

The book seemed very much to dovetail together a lot of our shared influences, going right back to when we first met. Flannery O’Connor, William Faulkner and Cormac McCarthy loomed large in our formative years. Nick just happened to be tapping into the same sort of music, when we were younger, of the blues and country and folk and rock. So all these forces and influences all came together in this one book. The world was really interesting. And that opened it up for the music as well.

You’ve known Nick since the late 1970s. Can you give us a flavour of what Melbourne was like back then?

Oh, it was wild. It was just like the film: lawless. Weirdly enough, our first really in depth working experience was on Ghosts… Of The Civil Dead. I was attacked and my jaw was broken in two places. My entire mouth was wired shut. So I was talking to him through clenched teeth and having liquefied meals through straws. Literally, that’s how we started working about the script, talking about high security prison and violence, having been a victim of violence. There was definitely an edge to Melbourne. It’s got a real underbelly. There used to be a lot of police corruption and there’s always been a huge influx of illegal drugs, and with police involvement. That was very much prevalent in our youth. I grew up in the late Sixties in New Haven, Connecticut. I’d seen police shoots out in front of my eyes, a car chase with the cops leaning out the window firing bullets which sounded more like a cap-gun or a pop-gun, very anti-climactic. But the thing that impacted on me as a youth were all the cultural upheavals, going on Martin Luther King’s funeral march, the repeated black and white TV showing Robert Kennedy’s assassination. In a very short time, all my parents heroes had perished and been assassinated violently, whether they were the president all the way down to rock stars.

Can you tell us about the influence Michael Ondatjee’s Billy The Kid poems had on you and Nick.

Weirdly enough, when I was in Canada I had that as a teenager. It was only on the University of Toronto press, he was just a local university writer. I was blown away by that mixture of documentary realism and poetic prose. It was so like the movies I was watching – Peckinpah, Scorsese, Arthur Penn’s Bonnie & Clyde, The Godfather. It had a huge impact on me and likewise Nick loved that book. It was a real galvanising force, the Ondatjee book during that era in the Seventies. It was a very vibrant time, I might add.

Who else was on the Melbourne scene at the time?

It was the Little Bands scene. It was that whole post punk period where it was like a cottage industry. All these people we knew who had their own record labels, and we all went to certain venues to see the concerts, so it was all self generating. Between the local, tiny record shops and record companies and the venues there was this circular thing, where everyone we knew were forming bands and being in bands and then watching bands and listening to music. There was Missing Link and Au Go Go and these labels that are long since gone, but they picked up on Nick’s band. There was a band called The Reels Nick and I featured the singer in Ghosts… Of The Civil Dead [Dave Mason]. They had offers from every major record company in the world, but they were ferociously uncompromising. There was a whole two fingers up at authority. We had tiny venues where The Clash, Iggy Pop, The Cure were all going through, like the Crystal Ballroom. I had the job of filming those shows, working in the venue doing a recording for their archive. And then Nick, when he went overseas, they really took up.

How did Nick’s contributions for Ghosts… Of The Civil Dead come about?

He was already clued up on the whole music/prison thing, and the blues – all these characters came from literature and secondary sources. Then myself and the co-writer who was also producing, Evan English, did a lot more real research where we went into the prisons, so we took it somewhere more grounded in realism. But Nick did create these very flamboyant characters, and one of them of course was this character who was tailor made for him. Nick was a bit wild at the time, and it just suited his particular state to let him go off. We even created this set – I’ll never forget – we just had a basic plan of this guy entering the unit and just being so obnoxious: he drew on some experience when he was in a lock up in New York, and we reference self-mutilating which was very popular in high security prisons. So he got all these aspects and then just ran with them, because he couldn’t… he was too of the frame of mind, he couldn’t learn lines and work in a traditional sense. So we just let him rip.

Nick says his acting peaked with Maynard. Do you agree?

Yeah, even the ex-inmates who’d done a lot of hard time were wary of Nick. Let’s just say, we got him at the right time and tailored it to the state that he was in. Maybe that a little bit exploitative, but he didn’t seem to mind. [laughs] It’s his acting triumph.

I hear Russell Crowe was nearly cast in The Proposition. What happened there?

He was a big fan of Nick’s, and he was very keen on getting involved. He was quite a star at the time and it was a difficult negotiation. We talked about him doing the Ray Winstone role, but then we all agreed that the Danny Huston role was the most appropriate. There were all sorts of logistics and other reasons… tight schedules, and all that. We actually had a different cast. At one stage, we even had Liam Neeson involved and Danny Huston was going to play Ray Winstone’s role. It was a lot of moving pieces. Guy [Pearce] was the first one in, and remained loyal throughout. It took us years, many years to get that off the ground.

Nick is very much in charge in his music career. But in his film career, he’s more at the mercy of other, external factors – studios, budgets, schedules. Is that frustrating for him, or do you think he enjoys being part of something bigger than him?

What he hates is the whole dance and the politics and the pressures. He’s got very little patience for it. We all hate that, but he in particular, because he’s so used to things getting done his way. But actually there is also the aspect of losing himself and being part of the process, a craftsman, a collaborator in a very real sense, that he enjoys. So it’s pros and cons. The negative is all the time delays and the financial pressures and the politics. But the way the collaboration works takes him away from being the frontman.

What parallels do you see between Nick’s film and music careers?

For me, it’s a real treat because there is an extra cohesion you don’t normally get. Because you start with a script and end with sound and music. But we talk about music at a very early stage, when he’s writing the script, which is an interesting way of approaching scores and soundtracks. And there is in his writing. What makes him such a great scriptwriter is he’s got an ear for dialogue and he’s got a kind of… I came to film making via editing, and editing is all about rhythms and pace and likewise with music. I think there is a rhythm, a musicality in his scripts, that is quite special and unique. We love collaborating together, and when I’ve directed his music videos, it’s nice for me to lose myself and just facilitate his requirements as the frontman. But it’s very different mediums though, with music projects and music videos, and that’s something else that Nick has great grasp of.

What are your future plans with Nick?

He’s worked on another script, from another scriptwriter, that he has rewritten for me, which is my next film. It’s very different. It’s a contemporary crime thriller, so far set in LA, that we’re casting. So that’s very different for Nick and I. It’s called Triple Nine. But there’s numerous things we’re talking about, and we’re no the lookout to find the next thing. We’re always, as soon as we finish one thing, we’re talking about the next. There’s several things on the horizon.

Lawless is released in the UK on Friday