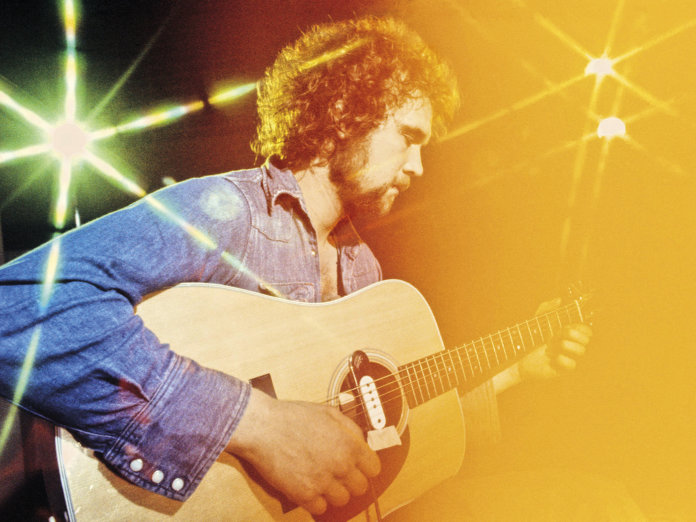

Instead of building on the modest success of his luminous 1973 breakthrough Solid Air, John Martyn dived straight back into Island’s West London studios to record the capricious, unruly Inside Out. As Graeme Thomson reveals in an extract from his new biography of the headstrong folk voyager, the a...

Instead of building on the modest success of his luminous 1973 breakthrough Solid Air, John Martyn dived straight back into Island’s West London studios to record the capricious, unruly Inside Out. As Graeme Thomson reveals in an extract from his new biography of the headstrong folk voyager, the album’s intoxicating, coke-fuelled experimentalism bemused the label but became Martyn’s personal favourite. “It wasn’t just a mad, drug-crazed romp,” insists one key collaborator. “We were completely in the zone with John’s music.”

“I’m not really a great joiner,” John Martyn told this writer in 2005, sitting in a beer garden in his adopted hometown of Thomastown, in Kilkenny. “I prefer being on the fringe.” That maverick sensibility is scored deep into his catalogue. For anyone seeking a single piece of evidence marking out Martyn as an instinctive non-team player, a man who bolted at the first sign of consensus or acceptance, a contrarian of the first rank, Inside Out is the place to start.

A foray into the furthest reaches of his musical mind, a dazzling and sometimes bewildering experiment in tone, form, texture, pace and placement, Inside Out arrived barely six months after Solid Air, by some distance Martyn’s best known and most acclaimed album. The only person who didn’t seem to love Solid Air was the man who made it.

“John always moaned about Solid Air,” says John Wood, the engineer who worked with Martyn on the album and its predecessor, Bless The Weather. “He never gave me the impression he liked the record much.” In the immediate aftermath of its release, Martyn publicly expressed his disappointment. “I’m not as pleased with it as I have been with previous ones,” he said. “It was all too rushed.”

In private, he was often more blunt. “He actively hated it,” says Jim Imlach, the son of Martyn’s great friend and mentor, the late Scottish folk singer Hamish Imlach. “I could tell you a dozen times where he said he hated that album, hated the songs. It was part of his journey, but he didn’t want it to define him. He wanted to be innovative. He was a stubborn sod.”

A free-jazz-orientated improvisation, Inside Out is Martyn’s freedom song, the most committed communique from the part of him which was in thrall to Pharoah Sanders, Dudu Pukwana and the Spontaneous Music Ensemble. A fuzzy miniature stitched together from a series of unruly, unmapped performances, it is beautiful and maddening; indulgent and inimitable. The splendidly cosmic cover art, depicting the artist’s inner thoughts as a fury of lightning bolts and thunderclouds, visualises the guiding principle of Martyn’s music: creation as the ultimate catalytic converter, spinning a ton of messy psychological shit into sunshine – and vice versa. Inside. Out. Outside. In.

As a deep descent into a storm-tossed subconscious, it reveals much about Martyn. In later years he would claim it was the only one of his records that he could stomach. “I dived in completely and created within very intense surroundings,” he said. “There was no distance, no self-consciousness. It’s probably the purest album I’ve made musically.”

It was as though his reward for the more streamlined magnificence of Solid Air was to cut loose from the moorings of conventional songwriting, an instinct which captures not only Martyn’s essential spirit, but the quintessence of Island Records. “Chris Blackwell let his artists develop through their formative period,” says Martyn’s greatest musical foil, the bass player Danny Thompson. “He allowed them to breathe.”

Inside Out was recorded in July 1973 at Island’s Basing Street and Fallout studios. Richard Digby Smith was de facto co-producer, although he is not credited as such. The album drops a significant clue regarding its intentions in the opening seconds. Martyn comments that whichever sounds the musicians had been creating prior to the listener’s arrival had felt “natural”, before he slides sleepily into the opening track, “Fine Lines”. We are immediately aware of the fact that we’re hearing a mere excerpt from a far greater whole.

Working with Thompson on bass, Martyn drew from a remarkable pool of musicians, most of whom were readily available to him on his doorstep at Island. Fallout, the label’s second studio, was housed in the basement of their headquarters at 22 St Peter’s Square. “Steve Winwood would have been around all the time,” says Digby Smith. “You would grab these people, put a bit of Hammond on the track. Remi Kabaka would play on anyone’s music, he always had his congas in the back of the car. Chris Wood would walk around with the sax strap around his neck, ready to go into action at any moment. It was almost like one giant band of all the Island artists. Everybody would play on everybody else’s record, you only had to ask.”

The shape of the sessions was often dictated by the strictly rationed licensing laws Britain inflicted upon itself in 1973. Access to the Cross Keys pub over the road was considered sacrosanct, for lunchtime drinks and further liveners before closing time. The session off-cuts include 20 straight takes of “The Glory Of Love”, during which Martyn gets progressively and audibly more inebriated. At other times, the players broke from almost spiritual levels of creative interaction to throw beer bottles across the studio.

“There was a considerable amount of chemical assistance required throughout, and John was very generous,” says Digby Smith. “It was a plastic bag of white powder, several ounces of the stuff. We used to keep it in one of the two-inch tape boxes, and it was the first thing you would do on arrival, lines of coke the length of the desk. It was epic. It fills me with fear and dread thinking about it now.” One session lasted from Friday evening until Monday lunchtime. “I can’t remember whether I got into a cab or an ambulance. We worked on one song, the same song, for three and a half days. It was such a ball. We were all young, incredibly fit, and as mad as a bag of spanners.”

It was very different to the more focused, structured sessions for Solid Air. “I was older, and I came up through a very disciplined background, learning my craft at Decca studios,” says John Wood. “I couldn’t – and still can’t – hack undisciplined messing about in a studio. It unfocuses the project. If you don’t keep knowing what you’re going to do at each point, it just becomes a mess. And John was not a disciplined worker, that’s for sure, which is probably why he didn’t like working with me.”

Digby Smith is at pains to emphasise that “it wasn’t just a mad, drug-crazed romp. We were working, we were completely in the zone with John’s music. He was absolutely serious about the heart of the music, and pretty clued up technically about how he wanted it to sound. He had an assortment of pedals; there was lots of technical stuff to keep you on your toes. It was such fun. Danny and John were just such a comedic duo. It never turned nasty. Even in the most epic and unnatural circumstances, I cannot recall a single moment of unpleasantness or uneasiness.”

The lack of focus, at least in the traditional sense, was partly the point. Martyn wanted Inside Out to be “heavier… with more blowing”. On its eight-minute centrepiece “Outside In”, his viciously manipulated guitar seems to spiral into inner space and play around with the construct of time. The result is the high point of Martyn’s explorations with the Echoplex. Rooted in extemporised performance, the track required a dense tapestry of treated and layered guitars to find its shape.

“He had an idea in his head,” says Digby Smith. “He was really into his guitar going through delay pedals, the Mu-Tron [phaser] and the Echoplex and recording the guitar with effects on it. He would overdub wild, crazy, avant-garde, random phrases on guitar, and think nothing of doing four or five takes of that. Then I’d say, ‘You and Danny go and have a pint, and I’ll sift through these takes and pick out the best bits and make a compilation.’ What you hear has a certain amount of manipulation, some comping, which he was always happy to let me do.”

The Rolling Stones’ in-house saxophonist Bobby Keys added horn to its later, becalmed passages. He “just staggered into the studio after doing some overdubs with the Stones and said, ‘Can I blow?’ and we said, ‘Sure’,” said Martyn. His playing evokes a beach firework display rendered in slow motion.

The instrumental “Eibhli Ghail Chiuin Ni Chearbhail” was based on a pretty Irish air dating back to the early 1800s. Recorded by The Chieftains in 1971, the Gaelic title broadly translates as “The Fair And Gentle Eily O’Carroll”. Martyn took a sharp axe to all that tradition, deploying a wickedly fuzz-toned guitar on the melody line and a churning drone for the bottom end. The result is a warped Celtic death dirge, forlorn and ominous, which sounds as though it is powered via a crank handle.

The barely structured “Ain’t No Saint”, with its hot-potato scatting and fluttering dynamics, resolved itself in the sharp clack of Kabaka’s arrhythmic congas and some wonderful Arabesque guitar figures. Spanish and North African inflections featured again on the instrumental “Beverley”, a sad, soft, disquieting blend of sawed string bass, splashy cymbals and the cries of Martyn’s treated guitar. “Look In” was all jazz-funk grunt and grind, a pre-echo of the music Martyn would go on to make in the ’80s. Like “Outside In”, it became a playground for extended forays into improvisation in Martyn’s subsequent live shows.

Inside Out is not short of such voyaging, guided by surf and stars rather than map and compass, yet there are wonderful songs, too. “Fine Lines” is one of his very best, as tender a song of friendship as Martyn’s signature song, “May You Never”, except that here the love extends beyond a brother to a brotherhood of the “finest folk in town”. It reeks of woozy late-night gatherings and the 5am pre-dawn reckoning, when the music settles to a faint pulse, the bright edge of the chemicals begin to soften and blur the senses, and the awareness of “the love that’s in us all” is a matter of peaceful certitude.

“Ways To Cry” is a slurred susurration, vowels strung together like worry beads; “So Much In Love With You” is a late-night jazz noir, with lascivious saxophone from Keys, gumshoe piano tinkles from Winwood, rim-crack syncopations and sharp blues licks from Martyn.

Taken in the round, Inside Out is perhaps the closest Martyn ever came to a concept album. The breezy version of Billy Hill’s “The Glory Of Love”, first made famous by Benny Goodman in 1936 and a standard thereafter, is no throwaway – Inside Out is a love theme for the wilderness, clinging to its lifeline amid stormy seas. “Make No Mistake” might be his deepest dive into the agonies of the heart and the duality of the feelings it laid bare. “The only politics that work is the politics of love,” Martyn pronounced, at the same time acknowledging that conforming to such an ideology was always going to be something of a stretch. “Love is something I like to foster in the family but at the same time I’m very loud, quite mad and can be an exceptionally nasty person.”

Inside Out was released on October 1, 1973. Martyn later expressed satisfaction at its intentions, if not always its execution. “I would have liked to have attacked it with more technical ability,” he said. “What you get is a kind of vision of what I would have liked to have been playing.”

Ian MacDonald’s review in NME astutely recognised that Martyn “has reached his long-promised fruition whilst simultaneously forfeiting most of his commercial potential”. For all its light-headedness, its drifting refusal to be anchored, Inside Out is a remarkably lucid record in one respect: it was an album designed to set the modest industry gains Martyn had achieved through Solid Air firmly into reverse. It was a hard sell for the suits, even suits as dressed down as those at Island Records. “I remember it being not the right record after Solid Air,” says Chris Blackwell. “Maybe it would have been better a couple of records later. I think people wanted another Solid Air, or an evolution somewhat from Solid Air. Inside Out had a whole different feel to it.”

“It wasn’t what was required!” Martyn recalled in 2005, laughing over his pint of cider and quadruple vodka. “I have no regrets about that. I’d rather have the respect of my peers. I’m very happy there.”

Small Hours: The Long Night Of John Martyn is out now, published by Omnibus – click here to buy a copy.