Fried – the title an apt description of Cope’s state of mind – was recorded in two weeks in Cambridge’s Spaceward Studios, again with Steve Lovell producing, Kate St John on oboe and cor anglais, and Skinner providing guitar on four tracks, including the opening “Reynard The Fox”, which perfectly summed up Cope’s new musical philosophy – looking backwards and retracing musical steps that might have been ignored the first time around. Accordingly, “Reynard” takes its title from an old folk song and its riffs from a garage-rock classic.

“I figured out this new formula,” Cope explains. “The person who writes the riff is the originator, the person who copies the riff is the rip-off, and the person who does the third version is just the traditionalist. So I figured that, you know, ‘I Can Only Give You Everything’ by Van Morrison and Them has been ripped off so many times by garage-rock bands to write songs that were just as good.”

Recording was overseen by Cope’s new spirit guide, Brian Wilson. A picture of the Beach Boy was framed in the studio, and he and Lovell would regularly consult it for advice during sessions. A bed was also installed in the control room, with Cope regularly cajoling the producer into resting in it à la Wilson. “Steven was a real acidhead from the ’70s, and he absolutely rallied to the kind of character I needed him to be, because I think secretly he was that in any case. So yeah, he did become an ersatz Brian Wilson. He spent time in the bed, but only out of obligation, because I was so needy: ‘You’re not spending much time in that bed!’ ‘I’ll have a little rest, then…’”

When he wasn’t consulting Brian, Cope would crawl around the studio under an antique turtle shell he had recently bought in a junk shop, or put down his vocal parts stark naked. Kate St John and Donald Ross Skinner agree, though, that Cope was clearly focused on the music despite his antics. “Fried was definitely the more out-there period,” remembers St John. “Julian was inhabiting an area under the mixing desk for a while [laughs]. But even so, he was absolutely fine when you were with him. He didn’t seem lost when I worked with him on the records at all. He’s always so nice, just a lovely person to be around.”

“We worked very quickly,” says Skinner. “He knew what he was going for musically; he had a clear picture, and however his mind was at the time, it was still functioning artistically. He was always very lucid… but bonced.”

Indeed, Fried is Cope’s first bona fide classic – “Reynard The Fox” is a powerful opener, moving from a paean against bloodsports into a spoken-word recollection of his infamous onstage meltdown, with Cope screaming, “He spilled his guts all over the stage!” “The Bloody Assizes” tells the tale of the Tolpuddle Martyrs over raucous rockabilly, while the oboe-led, psych “Laughing Boy”, both dreamy and sinister, finds Cope imploring, “Oh no, don’t cast me out of here/I said, no, I got no place to go,” like a little lost boy.

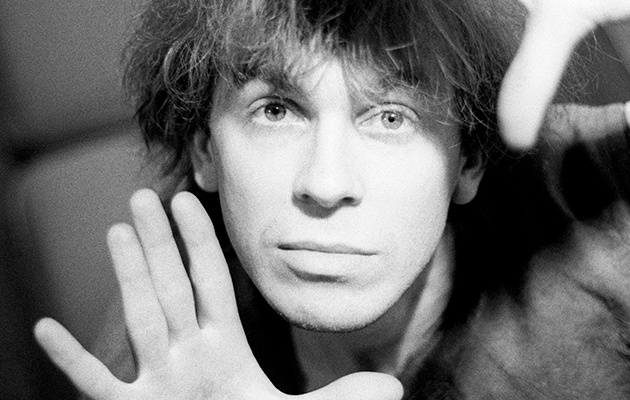

In line with his new self-imposed budget, the cover of Fried, depicting a crouching Cope naked under his turtle shell on Alvecote slag heap in Warwickshire, cost only £215 to shoot. The location was in fact only 600 metres from the priory where World Shut Your Mouth’s cover had been shot earlier in 1984. “I was really going from the macrocosm of hoping to be a world artist to suddenly being utterly localised in my worldview,” explains Cope. “My 1984 albums were not quite bucolic, but they were non-urban. The day we shot the Fried cover, absolutely without our knowledge, they were burning off the crops nearby, so if you look on the back, there’s all this smoke. It just has this amazing late-autumn feel to it. I suppose it is quite dystopian, isn’t it? I mean, where the fuck would that be?”

In many ways, Fried marked the beginning of the rest of Julian Cope’s career. Even though 1987’s Saint Julian took him back to the charts, and 1991’s Peggy Suicide and the following year’s Jehovahkill pushed his sound and message gloriously far-out, Fried marked the emergence of Cope as a truly unique voice, plumbing rock’n’roll’s golden age and connecting with nature, in order to look to the future.

When it charted at No 87, though, Polydor decided not to renew Cope’s contract, and cancelled the planned 12-inch release of “Sunspots”, Fried’s most commercial song. The album’s magic was already working, though. “In the end, the truth of World Shut Your Mouth and Fried was strong enough to turn the right people on and to gain faith in people in the music business who hadn’t absolutely lost their mind trying to sound like Dollar. The people did rally to me, but I actually had to release those albums in order to prove to them that I was still a functioning human being.”

Cope himself draws comparisons between World Shut Your Mouth and Fried, and Neil Young’s first two albums – the first slickly produced and played mostly by Young, Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere more ramshackle. Young’s adoption of the untested Crazy Horse as his backing band on that album also mirrors Cope’s championing of the 17-year-old Skinner during Fried.

Perhaps most crucially, the legacy of these two albums, Fried especially, can be seen in Julian Cope’s still-herculean work ethic. He’s usually up at 5am these days, writing and recording songs, but more likely working on his latest book, an out-there novel or a megalithic non-fiction tome. “The metaphor on these two albums was industriousness and capability,” he explains. “I was determined to do two albums very quickly. When I was 16, I read this essay called ‘The Metaphysical Poets’ by TS Eliot, and one of the things he said, which has stuck with me for my entire life, was to the effect of, ‘We live in a very fortunate culture as artists, because all that our culture requires is that we poets, we artists, we authors, do not sit and merely read poetically in our gallery but we bring forth something, to educate, to edify and to entertain.’ And I thought, ‘Well, if that’s the covenant between me and the audience, then bring it on.’

“It was about being serious, and also being serious about making a cunt of yourself, and I think that’s very important. Being naked under a turtleshell, I can’t say that wasn’t really in, in the ’80s, because that wasn’t in in the ’70s and that wasn’t in in the ’90s, but it did sum up my metaphor. It was ridiculous. But at least it was almost valiantly ridiculous. And wasn’t rock’n’roll forged in the fires of Saturday entertainment? But it does mean you’ve got to be really good.”

Double-CD reissues of World Shut Your Mouth and Fried are out now on Caroline International