The War On Drugs’ new album, Lost In The Dream, is out on Monday (March 17). Here, in this feature from Uncut’s November 2011 issue (Take 174), Sam Richards joins Adam Granduciel’s friend and collaborator Kurt Vile on tour in California to uncover the blood ties between Vile’s Violators and ...

The War On Drugs’ new album, Lost In The Dream, is out on Monday (March 17). Here, in this feature from Uncut’s November 2011 issue (Take 174), Sam Richards joins Adam Granduciel’s friend and collaborator Kurt Vile on tour in California to uncover the blood ties between Vile’s Violators and The War On Drugs…

___________________

Kurt Vile is sitting on the sidewalk outside the Troubadour, the fabled Los Angeles club on Santa Monica Boulevard, where tonight he will play the second of two shows as a special guest of Sonic Youth’s Thurston Moore.

History hums in the walls of the Troubadour. This, after all, is the place where Janis Joplin and Jim Morrison caroused nightly, James Taylor and Carole King performed “You’ve Got A Friend” for the first time in front of an audience and where, among many others, Tom Waits, Elton John and even Guns N’ Roses kickstarted their careers. On any given night in the early ’70s you might wander in and find the club’s front bar full of rock royalty – CSNY, The Eagles, Poco, Joni Mitchell, Gram Parsons, Van Morrison, Tim Buckley, Randy Newman, Harry Nilsson and innumerable other singer-songwriters, scene-makers, groupies and hangers-on.

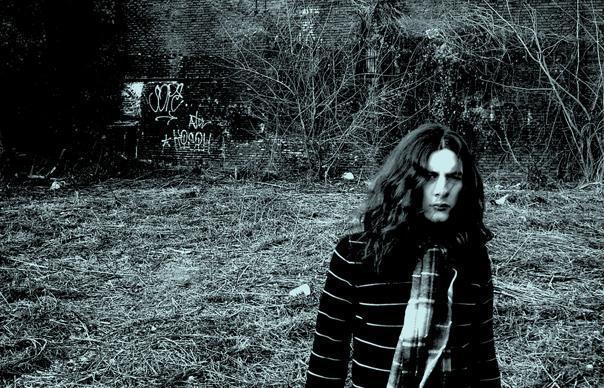

“It really is pretty awesome to be on the same stage that bands like The Byrds and The Flying Burrito Brothers played so many times,” says Vile, the Philly singer-songwriter with the punk rock name, the grunge mane and the folk tunings. “One of the bouncer guys,” he adds, his voice dropping to an almost conspiratorial whisper, “has all these funny stories about Bonnie Raitt and Linda Ronstadt getting into fistfights.” He shakes his head in something approaching disbelief.

Vile, it’s not a surprise to discover, is a keen student of rock history. By his own reckoning, he’s consumed eight Rolling Stones biographies – he recommends Robert Greenfield’s STP if you want “the real debauched one” – plus books galore about Dylan, Springsteen, Neil Young and any other rocker whose life has turned to legend. “I always had my own dreams of writing songs and going on the road, so reading these rock biographies became an obsessive thing for me. When you listen back to these people’s records with the knowledge of how they recorded them and all that was going on in their lives, it becomes like virtual reality.”

___________________

It’s taken a while, but Vile is gradually beginning to insinuate himself into the grand narrative of rock’n’roll that he worships so much. A consensus is quietly forming around his fourth album, Smoke Ring For My Halo, an appealing concoction of bummed-out classic rock vibes and slacker insouciance that was voted the best album of the first half of the year by readers of Uncut’s Wild Mercury Sound blog.

Even more gratifying for Vile have been the fond eulogies from several of his teenage heroes. When a copy of Vile’s previous album Childish Prodigy found its way into the hands of J Mascis, the Dinosaur Jr guitarist immediately recruited Vile to add mellow acoustic textures to his solo album, Several Shades Of Why. “I like the atmosphere he generates,” says Mascis. “He plays stuff I wouldn’t think of.”

On this current tour, he’s a guest of another alt.rock titan, Thurston Moore, who reveals how Kurt’s early records became a fixture on his and Kim Gordon’s “kitchen playlist”. “The way he mixes his records is very distinct, real personal,” enthuses the Sonic Youth man. “He has such a good positive energy. He’s a funny guy, and a beautiful songwriter.”

___________________

Kurt Vile’s destiny was mapped out for him from the moment that his father, a fan of bluegrass and roots music, but evidently not 1920s Marxist musical theatre, unwittingly gave him the best punning punk rock name since Dinah Cancer. Growing up in a family of 10 kids in the Landsdowne neighbourhood of Philadelphia, most of Vile’s childhood experiences were soundtracked by his dad’s tapes of Doc Watson or John Denver, “Or Rusty Kershaw, this Cajun guy, who played on On The Beach.” Vile was encouraged to play music at home, although his first instruments were the trumpet and the banjo. “I wanted a guitar but it was too rock’n’roll or something,” he smiles. Vile dutifully mastered the banjo anyway, and these days he still often employs its distinctive open tunings when playing guitar.

At 17, inspired by the wry DIY fumblings of Beck and Pavement, Vile had an epiphany with a four-track tape machine and began recording his own songs at a prodigious rate. He scraped through art school before travelling cross-country with his girlfriend, settling in Boston where she attended grad school at Emerson College. There, he made friends with a bunch of college students who turned him onto “more cool music, like John Fahey and Brian Eno”. Yet despite continuing to amass a catalogue of quirky home recordings, the breakthrough never came.

His lowest point came when he found himself at a pitiful distance from his rock’n’roll dream as it was possible to get, driving a forklift truck for an air freight company in Everett, Massachusetts. Then again, it was just the kick up the arse he needed. “I was away from my childhood friends, working at this shitty warehouse, driving a forklift. And obviously the job totally sucked but I’d play all the time and all these songs just poured out of me. You get in a rut, but that’s where inspiration comes from.”

Moving back to Philly, he was galvanised by meeting Adam Granduciel of The War On Drugs (see panel) and the pair began working up the cache of songs that Vile would continue to draw on for 2008’s uber-indie debut, the sardonically titled Constant Hitmaker, right through to this year’s Smoke Ring For My Halo. “The song ‘Ghost Town’ on Smoke Ring… came from that period,” he confirms. “It’s about trying to climb out of something, aiming for something you can’t quite reach.”

___________________

It’s sentiments like this that have found Vile talked up as a kind of lo-fi Springsteen, although it’s difficult to imagine The Boss ever singing, as Vile does in “Runner Ups”, of wanting to “take a wizz on the world”. More often, Vile resembles a later school of American songwriters: on “Peeping Tomboy”, when he sings, “I don’t wanna change but I don’t wanna stay the same”, you’re immediately put in mind of Evan Dando’s “Don’t wanna get stoned but I don’t wanna not get stoned” dilemma. And Vile has a habit of signing off his verses with a verbal shrug – an “Aw, hey, who cares” – that reminds you of another Kurt, and his “Oh well, whatever, never mind.” Where many rock songs strive to make statements and end up sounding glib, Vile’s honest demurrals are wholly refreshing.

“There’s a million ways to answer a question, and who’s to say which one is 100 per cent right?” he says. “I never want to be too straight-up literal, I like to leave things open.” He reaches back into those rock biographies for an analogy. “It’s like the difference between Dylan and Phil Ochs. Dylan would always make it broad, so anyone could relate at any time, whereas Phil Ochs would write songs about very specific events. That’s where Dylan’s insult came from, ‘You’re not a folk singer, you’re a journalist!’ It’s why I strive to make my music timeless.”

Indeed, the sarcastic snarl of Smoke Ring…’s “Puppet To The Man” has more than a hint of electric Dylan about it, Vile hitting back at the indier-than-thou bores who take umbrage whenever an artist tries to progress.

“When Smoke Ring… first leaked there were a load of nerd blogs who totally hammered it because it wasn’t so lo-fi or fucked up or something,” he says, “which was frustrating because to me it’s a more honest record then my previous ones – it’s just straight-up music. Like Neil Young says, your past is your own worst enemy, and people are always going to hold your new thing up to everything else that you’ve done. But I’m proud of the record and I couldn’t be happier with its reception.”

Nine o’clock the following night, and we’re roaming the streets near San Diego’s Casbah venue in search of fish tacos. Vile is weary but content, having broken up the journey between LA and San Diego by stopping off in Costa Mesa to record a raucous impromptu cover version of Keith Richards’ “Before They Make Me Run” with Jennifer Herrema of Royal Trux/RTX.

He clearly gets a kick out of collaborating, and diversions like these help break up the monotony of life on the road, which he has memorably compared to Lord Of The Flies. “I wanna beat on a drum so hard/’Til it bleeds blood” run the mordant lyrics of “On Tour”, and there is a definite frisson to watching him sing them live, flanked by the very people whose heads he must occasionally imagine skewered on stakes in the woods.

“It’s psychological warfare sometimes,” he smiles. “I wrote that on my first tour with The Violators. You’re just getting to know these people and all of a sudden you’re stuck in a van and it’s like being stranded on an island. Touring is hard work, especially with me being a new dad [Vile’s daughter was born in 2010], but then again, when I’m home I always have the itch to play. I’m stoked to be in this position.”

It seems that The Violators [Granduciel, third guitarist Jesse ‘Turbo’ Trbovich and drummer Mike Zanghi, there is no bassist] will have a bigger role to play on Vile’s next album. “Definitely, with all this touring we’re getting so tight. There’ll be rocking out for sure but it’s not going to be like Black Sabbath or anything. I just want to get in the studio and give it my all. A big element of my music is trial and error, but I want to try to execute songs with a little more authority.”

___________________

Today’s session with RTX has given Vile some ideas on how to maintain the intimacy of his records while expanding their scope. “It was cool recording with Jen, they cranked the song through the PA. Sometimes when you’re used to playing a song live and suddenly you’re there in a studio hearing it through headphones you can’t summon up the same energy. So losing the headphones seems like a good plan to get the raw rock’n’roll vibes. Overdubbing’s fine, but I like the blueprint of a song to be as natural as possible.”

In some artists, this yearning for authenticity might seem like a pose, but Vile is too ingenuous a performer for that to ever be the case. Jennifer Herrema makes a shrewd assessment: “Nothing about his music feels contrived. Usually music is just a little subsection of somebody’s life and there’s very few people, like Kurt, where their music and their life are all one thing.” If Vile’s having a bad night on stage, you can immediately hear in his voice; it only means that songs such as “Ghost Town” and “On Tour” bite even harder.

“If that’s how it comes across then that’s cool,” says Vile, breaking into a goofy grin, “because even if it’s a little out of tune, or it’s totally raw, the people who understand the music know that it comes from the heart.”

The reason his songs can stumble from glee to despair to resignation within the space of a few lines is because that’s how things really are. “Life can be beautiful,” he says, “but it can be super fucked-up at the same time.”