SCHMIDT: Actually, the recording of the title song wasn’t much different from the recording we had done before. The special thing about this title was, we used this rhythm machine at this time, this very simple machine, little thing which actually, you know, bar pianists use. That was a little rhythm box. It started with this rhythm machine and Michael [Karoli] playing a rhythm guitar and me joining in with these riffs, and Holger’s bassline. That was all done live in the studio in one go. But there are of course things edited, like the melody, which might have refined in overdubbing.

CZUKAY: The drum machine was used on Tago Mago for the first time, and especially Jaki was using it, an artificial instrument, not so much like a drum machine, but on “Spoon” it was used for the first time like a drum machine.

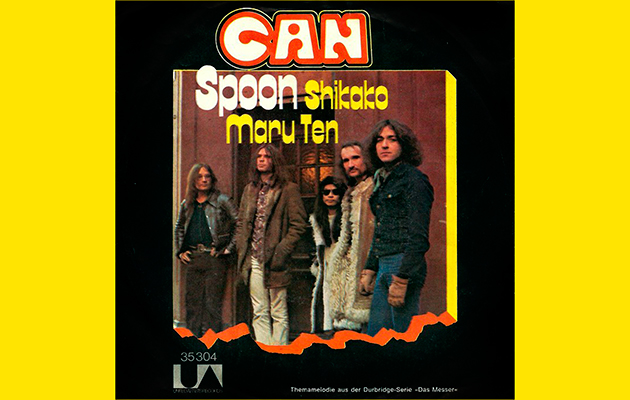

LIEBEZEIT: I don’t mind drum machines. To make a synthetic attempt to have a real drum there, that idea I don’t like so much. “Spoon” was the biggest hit we had in Germany, and that sound was one of the first rhythm boxes, a Farfisa rhythm box. It could play bossa nova, tango, jazz, waltz, all kinds of dance rhythms, and you could also press down all the buttons at the same time and get that mixture of everything. It was fun – we didn’t take it too seriously.

SCHMIDT: It was the first one, certainly in Germany, nobody had heard this kind of sound, that was one of the things that this funny director was so… for him that was so unusual, uncommercial, and yeah, I don’t rememver any piece at that time, 1971, using a drum machine, esspecially using it rhythmically in this weird fashion.

CZUKAY: I remember the drum machine very well. Jaki always reacts to something which is machine-like. Because he felt the drum machine was invented to bring a little bit of human feeling into everything. So he is more than the drum machine, he can absolutely repeat something for ever. It was even from the very beginning, because Jaki was playing free jazz before, and he said to me, “If I want to play free jazz, then I could take a sack of peas and hang it up over the drums, and open it and then the peas could fall down.”

SCHMIDT: It was actually more Michael and my idea, and we three had to convince Jaki to use it, to play to it. At first he was a bit reluctant. And then it was more or less Michael who started with a guitar riff, which was using the box actually not in the sense it was programmed, so let’s say it was foxtrot, beguine, whatever these old fashioned boxes had. And he did not use it as it was programmed, but used it against its rhythm. So not starting on the ‘one’ that’s indicated, but on the two or whatever. And that became so interesting that that was Michael that had this idea, and his guitar riff together became such an interesting thing that Jaki really joined in and there it was, there was the groove, and that was always the most important thing. That was always the basis of everything we did: the groove had to be right, and all of a sudden the groove was right. Everything was building on it…

CZUKAY: Working with the machine and getting the machine not to overstretch the machine, it was typical of Jaki not to do that. This was one of the most necessary steps for us to become more professional.

SCHMIDT: When you listen to the live version of “Spoon”, for instance the long version on The Lost Tapes, then you hear how much different live versions could be. It’s really worked out, and carefully worked out, but even if there were edits, any business in Can was always that Michael, Holger and me worked out the structuring of anything and Holger was the one who had the craft to edit. He did the editing, but the decisons were always made together. Jaki didn’t like to take part in this kind of busness, and that’s why you don’t hear edits. Because by the end Jaki would have gone crazy if he had heard the edit and it would have destroyed the groove. The groove wouldn’t have been right in an edit. And then it had to sound perfectly natural. Which was basically a structural decision first, and then of course the craft to do it right.

CZUKAY: This time Jaki didn’t need to play heavy, he could play softly, and then the [new Neumann] condenser microphone was recording everything perfectly, that was a big change here. We could mic him up with the overheads, quite far away from the drums, and the room would allow us to do that. Previously, we had dynamic microphones and the distance from the instrument to the mic was quite narrow. It was a difference suddenly: we were trying to become more sensitive. I think with “Spoon”, we had consumed all the professional tapes which I had, so then I had to take some home tapes of my own, one from 1955, I found it in the garbage. Because I was working in a radio shop, and they were throwing it away. And we used this tape, and it was still working very fine.

SCHMIDT: Damo never made what you could call proper lyrics, because it always was a kind of dada mixture of totally meaningless syllables and some words and phrases which came to his mind. And actually the whole thing in Can was more using the voice as an instrument, as one of the five instruments – it never had this kind of lead singer. And above all the lyrics never had this sense of transporting any kind of message, it was just music.

CZUKAY: This is not like Ian Curtis, whose lyrics are really important – no, I think our lyrics are not important, not at all. It was a companion to the knife [das Messer], less aggressive.