MARTIN REV: Before Suicide, I was doing a band called Reverend B, a selection of anywhere up to nine or ten improvising musicians. We played around New York, and did two shows at The Museum Of Living Artists, a space near Broadway, and that’s where I met Alan, in 1969. I would return there as a haven to get off the streets at night, and Alan was living in there. Alan was definitely on a very serious edge: the way he looked, what he was doing. He was looking for something. We were in the same place: when I first met him, he had his ear inside this little two-track tape recorder, trying to hear the feedback. He was already working with a guitarist. They were both visual artists, experimenting with sound. I had drumsticks, and started to drum on the floor. That’s how Suicide started. Originally, it was a wall of sound. The words were essentially shouts or screams. Alan blew trumpet. I played drums with one hand and keyboard with the other. The guitar player left after about a year. By then, I was thinking strongly about a drum machine. I started hearing a new way to do sound. I was familiar with drum machines not from rock, because they really weren’t being used, but from very kitschy performers: guys you’d see at weddings and in hotel lounges. It was a different space, a different dynamic. When I plugged in the drum machine, I heard it immediately.

MARTY THAU: In 1972, I was managing The New York Dolls, and established a residency for them at The Mercer Arts Centre in Greenwich Village. I started booking other groups, and that’s how I encountered Suicide. They were particularly outrageous. Alan would wear a black leather jacket with this big heavy chain around his arms and neck. He’d jump into the audience and get right up close to the most conventional-looking person he could spot, then sing right into their face to Rev’s loud, droning keyboard. To the uninitiated, it was a frightening show.

CRAIG LEON: Suicide were actually the first New York band I saw when I first moved to the city, around 1972. It was amazing: Alan doing this whole James Brown thing, whipping people with chains. Rev had their sound down from the beginning: wiring everything through a radio amp and using the little rhythm box and distorting it.

MARTIN REV: I wasn’t hearing keyboards the way, say, Emerson Lake and Palmer did. I wasn’t into filling in between other instruments. I was hearing an incredible amount of potential, new territory, feedback.

MARTY THAU: People hated Suicide.

CRAIG LEON: People would throw rocks at them. They were much more extreme than the punk stuff. They weren’t well liked.

MARTIN REV: Well, The Dolls always liked us. David Johansen was into it right away.

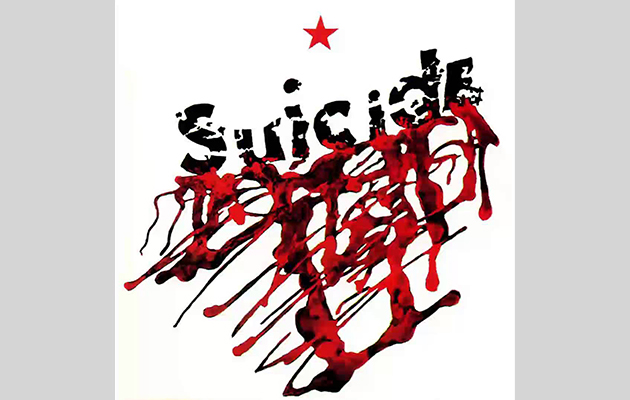

MARTY THAU: People didn’t like that this was a band that didn’t have guitars, didn’t have drums, and had the effrontery to call themselves Suicide.

MARTIN REV: It took six years before we got the chance to do the record. What we were doing was too radical to immediately be embraced. It’s often suggested we didn’t have guitars due to some conceptual agenda, but there wasn’t any of that. A guitar just didn’t make sense with us. There was a clarity in what was coming out there that didn’t need to go backwards.

MARTY THAU: I hadn’t seen them for a while, then in 1976, I ran into Rev and he told me they were going to play Max’s Kansas City. I went, and they were like Little Richard meets Iggy Pop meets Mick Jagger in a dark alleyway someplace. I thought, gee, I better sign these guys, because I was getting ready to open Red Star records.

ALAN VEGA: Going in to do the record seemed to happen over night. Jesus Christ, what a change it was to do it in the studio, after all those years playing live. I found it a little difficult to adjust. But that studio was nice. Bruce Springsteen’s amps lying around in the background.