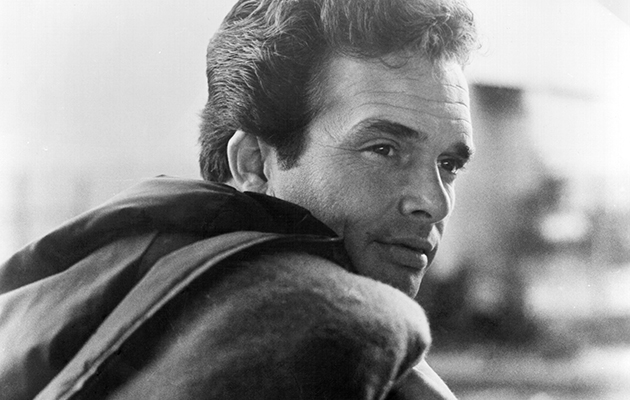

Merle Haggard eats at Lulu’s a couple of times in an average week, he reckons. His (fifth) wife, Theresa, isn’t much of a breakfast eater, he explains, and so he makes the 20-minute drive here from the ranch outside town where he has lived since 1980. The staff know him, and so do some of the customers, but if there was ever any excitement here about regularly dining alongside a genuinely legendary figure, everyone is past it: people say hi, he says hi back. He orders two eggs over medium, and a short stack of pancakes. In the background, a radio plays.

“I scan by the stations once in a while,” says Haggard. “But I don’t spend a lot of time listening. Never did, really. I still pretty much enjoy the same music that I’ve always enjoyed. Keeping up with my own productions really doesn’t leave me much time to explore what’s going on. The cream of the crop you hear about. I know that Rascal Flatts are hot, and that little girl, uh…”

Taylor Swift?

“Yeah, Taylor Swift. I know about those people, but I don’t spend a lot of time trying to figure out why.”

He laughs, not for the last time, a guttural, sputtering laugh that turns, not for the last time, into a cough (Haggard underwent surgery on a cancerous lung in November 2008). It must be strange, I suggest, listening to those radio stations and being Merle Haggard: you wouldn’t ever hear a song that you couldn’t hear yourself in.

“Yeah,” he smiles. “Either me, or somebody I was friends with.”

The seventy-odd albums Haggard has released since 1965 amount to one of the most astonishing and influential songbooks ever assembled by a single artist. Haggard seized the template bequeathed by his idols Bob Wills, Lefty Frizzell and Hank Williams – apparently simple songs which secreted considerable depth, songs which epitomised the specifically country knack of saying a great deal by saying very little – and breathed fresh vigour into it, layering it with the twanging Telecasters and breezy pop choruses with which Buck Owens and Wynn Stewart were, in the mid-1960s, re-orienting country’s centre of gravity from Nashville, Tennessee to Bakersfield, California (Owens’ ex-wife, Bonnie, would become the second Mrs Haggard). It’s a formula with which Haggard hasn’t since tinkered overmuch: no song on his terrific new album (I Am What I Am) would sound far from home on his first (1965’s Strangers).

“Somebody told me,” he says, “that once you have a reputation for making good records, then when you go into the studio you’re always just three minutes away from making a smash hit. And if you live your life that way, then you’ve always got a carrot out in front of you, and boredom will not be part of the picture.”