“The one thing that saved Mick at this point was Dylan,” Mick Ronson’s wife, Suzi, recalls in a terrific feature on her late husband by Garry Mulholland in the new issue of Uncut. She was talking about the shambles Mick’s career had become after he was dumped by David Bowie and his first two solo albums, Slaughter On 10th Avenue and Play Don’t Worry, had both flopped. Things hadn’t really worked out with the Hunter-Ronson Band, either, and you wondered where Mick might go from here when he unexpectedly hove into view as a member of Dylan’s Rolling Thunder Revue. Who could have seen that coming? You may remember me already telling you about interviewing Mick for what used to be Melody Maker, but here’s a bit of a recap. The first time I met him was in April 1975. The imaginatively named Hunter-Ronson Band, recently formed from the charred ruins of Mott The Hoople, had just played Newcastle City Hall. Back at the local Holiday Inn, we went up to Mick's room. He stretched out on a bed, me on a chair beside it. I was chatting away breezily about the first time I saw him on stage with Bowie, at the Bristol Colston Hall, on the Ziggy Stardust tour – “Hello, Bristol! I’m David Bowie. These are The Spiders From Mars. Let’s rock!” – when I noticed that Mick had gone a bit quiet. Further investigation revealed that he was in fact asleep. I sat there for a while, wondering what to do. By then, Mick was snoring away on the bed. And then he suddenly sat bolt upright, like something dead coming back to life, scaring us both. “I wasn’t sleeping,” he said, though he could have fooled me. “I was thinking.” About what? “David,” he said, a little huskily. And what Mick did next, for nearly two hours, was pretty much lay into Bowie, his former friend and musical partner, to whose career he had contributed so much before being cruelly ditched. Mick was in the kind of state by now that the words "tired" and "emotional" might have been invented to describe, and there were accusations of betrayal, admissions of hurt, expressions of huge regret over their squandered relationship. "I remember the Ziggy tour, he was so happy then," Mick had recalled, choking back tears. "He loved it and we were all having the time of our lives. And it got knocked on the head. It was such a fooking shame. America affected the band so badly. I'm going to be over there in two weeks," he declared with some determination, "and I'm going to see Dave as soon as I get there." And what was he going to say to "Dave"? "I'm going," Mick said, "to get hold of him and smack him across the head, right across the earhole, and try to drum a bit of sense into him. I wish he could be here, in this room, right now," he went on, "so i could kick some sense into him." And with that he nodded off again, and not long after that he was in America with Ian Hunter, the Hunter-Ronson Band starting a tour that was cancelled after a few shows because no one turned up to see them. By November, they'd split. For a moment, it looks like Mick's career is washed up, talk of another solo album convincing no one this is a good idea. And then to much speechless jaw-dropping astonishment, there's a picture of Mick in Melody Maker, on stage in Springfield, Massachusetts. He's kind of lurking in the background, surrounded by some familiar faces. Among them: Roger McGuinn, Joan Baez, Ramblin' Jack Elliott, Joan Baez and Bob-fucking-Dylan. Mick to the amazement of everyone I know has somehow ended up playing guitar in Dylan's Rolling Thunder Revue!! I've barely recovered from this information when I get a call from Anya Wilson, a friend of mine and a friend of Mick's. It's January, 1976. Ronson's in town, she tells me, and would like to meet up for a drink. I'm in a cab in a minute and heading for her place in West Kensington, where I find Mick happier than I'd previously known him, as straight talking as ever and a pleasure to be with. We get what happened to the Hunter-Ronson Band out of the way first. "Basically," he says, "Ian's afraid of doing anything if he thinks he's going to lose money. I'm a bit more of a gambler." And Bowie? Had Ronson followed up on his famous promise to belt Bowie around the head? Did he even get in touch? "I didn't bother," he says. "I didn't think it was worth it. I didn't really feel like listening to him making a lot of excuses. I didn't see the point." What I really want to know, of course, is how the former Spider From Mars ended up as part of Dylan's Rolling Thunder tour. Turns out that after splitting with Hunter, Ronson had started hanging out in Greenwich Village, making friends with a lot of the local musicians - Rob Stoner, T-Bone Burnett, David Mansfield, Bobby Neuwirth, Steve Soles - who Dylan would recruit for his bicentennial tour. One night, Mick was down at the Other End when he bumped into Neuwirth, who invited him for a drink. "He was with this guy," Ronson remembers. "And I looked at this bloke he was with and thought, 'Wait I minute, I know you.' And, of course, it was Dylan. And we talked, and he said, 'We're going on the road, why don't you come with us?' I just said, 'Yeah.' I honestly thought it was a joke. I didn't think I'd hear any more. Then Dylan phoned me, said the tour was going to happen. This was a Friday. He said rehearsals were going to start on Sunday and would I be there? I thought it were a fooking hoax. I really didn't think he was serious." On the first long day of rehearsals, according to a shocked Ronson, Dylan ran the band through 150 songs. The next day, they ran through another 100. "I were fookin' gobsmacked," Ronson laughs. "I'd never heard half of these numbers. And at first, I was completely baffled by them all. Really baffled and confused. Everyone else was already familiar with these songs and with each other and the way they played. I had a real problem fitting in, and I kept thinking I was terrible. I wasn't comfortable at all. But Dylan, Neuwirth, Stoner, T-Bone. They were all wonderful, really took a bit of time with me. And as we went on, I really grew into the music." Most of the time, Neuwirth and Stoner ran the rehearsals. So what was Dylan doing? "He was just. . .there," Mick says. "He'd play what he wanted to play. He'd come in and do his numbers. He did what he had to do and he did it well and quickly. He maybe wouldn't get too involved otherwise. I mean, he wasn’t pulling any big star trip. He doesn't have to. He doesn't have to say anything. With Bob, you just know. If there was something he was looking for in a song, you'd try to find it without being told. And that's the thing about Dylan. I'd follow him anywhere, no questions asked. That whole tour was this huge, huge adventure. A real treasure hunt. There was Joan Baez. McGuinn. Ginsberg - he's a grand lad, is Allen. There was Dylan. And there I was, too. For a lad from Yorkshire like meself, it were truly out of this world." He gets misty eyed there for a moment, thinking about it all. "There'll be nowt like it again," he says then. "Fookin’ nowt."

“The one thing that saved Mick at this point was Dylan,” Mick Ronson’s wife, Suzi, recalls in a terrific feature on her late husband by Garry Mulholland in the new issue of Uncut. She was talking about the shambles Mick’s career had become after he was dumped by David Bowie and his first two solo albums, Slaughter On 10th Avenue and Play Don’t Worry, had both flopped. Things hadn’t really worked out with the Hunter-Ronson Band, either, and you wondered where Mick might go from here when he unexpectedly hove into view as a member of Dylan’s Rolling Thunder Revue. Who could have seen that coming?

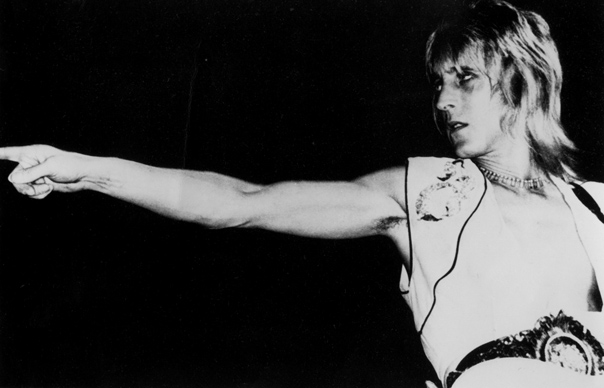

You may remember me already telling you about interviewing Mick for what used to be Melody Maker, but here’s a bit of a recap. The first time I met him was in April 1975. The imaginatively named Hunter-Ronson Band, recently formed from the charred ruins of Mott The Hoople, had just played Newcastle City Hall. Back at the local Holiday Inn, we went up to Mick’s room. He stretched out on a bed, me on a chair beside it. I was chatting away breezily about the first time I saw him on stage with Bowie, at the Bristol Colston Hall, on the Ziggy Stardust tour – “Hello, Bristol! I’m David Bowie. These are The Spiders From Mars. Let’s rock!” – when I noticed that Mick had gone a bit quiet. Further investigation revealed that he was in fact asleep.

I sat there for a while, wondering what to do. By then, Mick was snoring away on the bed. And then he suddenly sat bolt upright, like something dead coming back to life, scaring us both.

“I wasn’t sleeping,” he said, though he could have fooled me. “I was thinking.”

About what?

“David,” he said, a little huskily. And what Mick did next, for nearly two hours, was pretty much lay into Bowie, his former friend and musical partner, to whose career he had contributed so much before being cruelly ditched. Mick was in the kind of state by now that the words “tired” and “emotional” might have been invented to describe, and there were accusations of betrayal, admissions of hurt, expressions of huge regret over their squandered relationship.

“I remember the Ziggy tour, he was so happy then,” Mick had recalled, choking back tears. “He loved it and we were all having the time of our lives. And it got knocked on the head. It was such a fooking shame. America affected the band so badly. I’m going to be over there in two weeks,” he declared with some determination, “and I’m going to see Dave as soon as I get there.”

And what was he going to say to “Dave”?

“I’m going,” Mick said, “to get hold of him and smack him across the head, right across the earhole, and try to drum a bit of sense into him. I wish he could be here, in this room, right now,” he went on, “so i could kick some sense into him.”

And with that he nodded off again, and not long after that he was in America with Ian Hunter, the Hunter-Ronson Band starting a tour that was cancelled after a few shows because no one turned up to see them. By November, they’d split.

For a moment, it looks like Mick’s career is washed up, talk of another solo album convincing no one this is a good idea. And then to much speechless jaw-dropping astonishment, there’s a picture of Mick in Melody Maker, on stage in Springfield, Massachusetts. He’s kind of lurking in the background, surrounded by some familiar faces. Among them: Roger McGuinn, Joan Baez, Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, Joan Baez and Bob-fucking-Dylan. Mick to the amazement of everyone I know has somehow ended up playing guitar in Dylan’s Rolling Thunder Revue!!

I’ve barely recovered from this information when I get a call from Anya Wilson, a friend of mine and a friend of Mick’s. It’s January, 1976. Ronson’s in town, she tells me, and would like to meet up for a drink. I’m in a cab in a minute and heading for her place in West Kensington, where I find Mick happier than I’d previously known him, as straight talking as ever and a pleasure to be with.

We get what happened to the Hunter-Ronson Band out of the way first. “Basically,” he says, “Ian’s afraid of doing anything if he thinks he’s going to lose money. I’m a bit more of a gambler.”

And Bowie? Had Ronson followed up on his famous promise to belt Bowie around the head? Did he even get in touch?

“I didn’t bother,” he says. “I didn’t think it was worth it. I didn’t really feel like listening to him making a lot of excuses. I didn’t see the point.”

What I really want to know, of course, is how the former Spider From Mars ended up as part of Dylan’s Rolling Thunder tour. Turns out that after splitting with Hunter, Ronson had started hanging out in Greenwich Village, making friends with a lot of the local musicians – Rob Stoner, T-Bone Burnett, David Mansfield, Bobby Neuwirth, Steve Soles – who Dylan would recruit for his bicentennial tour. One night, Mick was down at the Other End when he bumped into Neuwirth, who invited him for a drink.

“He was with this guy,” Ronson remembers. “And I looked at this bloke he was with and thought, ‘Wait I minute, I know you.’ And, of course, it was Dylan. And we talked, and he said, ‘We’re going on the road, why don’t you come with us?’ I just said, ‘Yeah.’ I honestly thought it was a joke. I didn’t think I’d hear any more. Then Dylan phoned me, said the tour was going to happen. This was a Friday. He said rehearsals were going to start on Sunday and would I be there? I thought it were a fooking hoax. I really didn’t think he was serious.”

On the first long day of rehearsals, according to a shocked Ronson, Dylan ran the band through 150 songs. The next day, they ran through another 100.

“I were fookin’ gobsmacked,” Ronson laughs. “I’d never heard half of these numbers. And at first, I was completely baffled by them all. Really baffled and confused. Everyone else was already familiar with these songs and with each other and the way they played. I had a real problem fitting in, and I kept thinking I was terrible. I wasn’t comfortable at all. But Dylan, Neuwirth, Stoner, T-Bone. They were all wonderful, really took a bit of time with me. And as we went on, I really grew into the music.”

Most of the time, Neuwirth and Stoner ran the rehearsals. So what was Dylan doing?

“He was just. . .there,” Mick says. “He’d play what he wanted to play. He’d come in and do his numbers. He did what he had to do and he did it well and quickly. He maybe wouldn’t get too involved otherwise. I mean, he wasn’t pulling any big star trip. He doesn’t have to. He doesn’t have to say anything. With Bob, you just know. If there was something he was looking for in a song, you’d try to find it without being told. And that’s the thing about Dylan. I’d follow him anywhere, no questions asked. That whole tour was this huge, huge adventure. A real treasure hunt. There was Joan Baez. McGuinn. Ginsberg – he’s a grand lad, is Allen. There was Dylan. And there I was, too. For a lad from Yorkshire like meself, it were truly out of this world.”

He gets misty eyed there for a moment, thinking about it all.

“There’ll be nowt like it again,” he says then. “Fookin’ nowt.”