There are many revelations in Morrissey’s Autobiography, but perhaps the most unexpected arrives on page 194. “While in Denver,” writes Morrissey, “Johnny [Marr] and I attend a concert by A-ha, whom we have met previously and whom we quite like.” In the weeks leading up to the release – at last! – of Autobiography, we have been bracing ourselves for possibility that he would – or more depressingly, wouldn’t – divulge many truths. About his sexuality, his relationship with his former Smiths bandmates, what he thinks of Bowie… Nothing, however, appeared to prepare us for the comprehensive nature of Morrissey’s disclosures in Autobiography. Look - here he is, turning down parts in EastEnders and Friends, contemplating fatherhood, being detained by Special Branch, telling us that he represented his school in the 100 and 400 metres. And some stuff about a guy called Jake. As Dylan’s Chronicles or Neil Young’s Waging Heavy Peace have shown, it is possible for a musician writing an autobiography to successfully bypass niggly, pedantic details such as chronology, index and facts. Despite personally having little interest in great swathes of his solo career, the rock autobiography that’s given me most pleasure in the last few years has been Rod Stewart’s – simply because it satisfied the requirements of conventional storytelling. One concern was that Morrissey might also 'do a Dylan' and opt for a strategy of obfuscation: ignore The Smiths, write round some other quite important things, spend a lot of time going into forensic detail about the recording of, say, Southpaw Grammar. Instead, what we have here is a very traditionally structured book that moves at a satisfying pace through Morrissey’s life and times, from his birth in “forgotten Victorian knife-plunging Manchester” up to December, 2011, with our hero about to leave Chicago after a rapturously received gig at the Congress Theater. At 457 pages, that works out at just over 8½ pages for every one of Morrissey’s 52 years. Though, of course, some years are bigger than others. My overriding impression of Autobiography is the vividness of the detail. The bell that announces the end of the school day sounds at 3.40. With his Smiths advance from Rough Trade, he pays off a “lavish domestic phone bill of £80”. Ahead of their first Top Of The Pops appearance, the band are erroneously billed in The Sun as ‘Dismiss’. And so it goes. Such precise memories suggests Morrissey has been so profoundly affected by events that they have remained crystal-clear in his mind. Or perhaps he is a diligent archivist, with boxes full of clippings, cuttings and such ephemera. The book is littered with references and quotes from correspondence he's received: among the most affecting are a letter from Johnny Marr after the Smiths split and a postcard from Kirsty MacColl that he receives weeks after her death. The opening pages offer a fairly typical scene-setting: “Birds abstain from song in post-war industrial Manchester,” he writes, “where the 1960s will not swing, and where the locals are the opposite of worldly.” I’m reminded of Keith Richards’ Life, with its “landscapes of rubble, half a street’s disappeared… I couldn’t buy a bag of sweets until 1954”, a default setting for this kind of book. But Morrissey describes his childhood with a poet’s eye: “we are finely tailored flesh – good looking Irish trawling the slums of Moss Side and Hulme.” His descriptions of Manchester's working class districts are profound and poetic; the passages that cover the depravations suffered by his own family often heartbreaking. The relocation of Nannie, his maternal grandmother "from Queen's Square to a condemned house at 10 Trafalgar Square" captures the monstrous treatment of the working classes during the slum clearances. "Our lives are flattened before our eyes - as if the local council couldn't wait a minute longer for we pack rats to gather our trappings and transistors." The opening sections of the book also detail his schooldays. His inquiry into the cruel discipline dished out by a headmaster ("What job did he think he was doing? And… for whom?") or the sado-sexual behaviour of his PE teachers offers an insight into "the secret agony of a troubled child". As he remarks, with a weight of sadness, "This is the Manchester school system of the 1960s, where sadness is habit forming." This sadness dogs Morrissey for years to come. His first gig is T.Rex at the Belle Vue on June 16, 1972, then Bowie – “every inch the eighth dimension”– at the Stretford Hardrock in September, Roxy Music two months later, where Morrissey speaks to Andy MacKay who's pinball in the venue’s lobby. New York Dolls, Mott The Hoople, Lou Reed all follow. His prose captures the thrill of these formative musical encounters – a defining time in the life of the 12 year-old author. Roxy Music are "Agatha Christie queer,” he writes. It’s brilliant stuff. Johnny Marr arrives on page 145. As Morrissey points out, they had met previously – “in the foyer of the Ardwick Apollo” at a Patti Smith gig. “I am shaken when I hear Johnny play guitar, because he is quite obviously gifted and almost unnaturally multi-talented." In case you were wondering – and you probably are – Morrissey is extremely generous to Marr in the book – even after the Smiths’ split, when his emotional response to Marr veers from confusion to sadness. The Smiths section lasts 77 pages, from page 147 – 224; a good chunk – 16%, in fact – for what is essentially five years of his life. What, then, do we learn about the Smiths? That Mike Joyce drum kit was called “Elsie”, that Mick Jagger came to see them live in New York and left after four songs, that Craig Gannon was “a fascinating bungle”. While writing about their time together, Morrissey is positive about his bandmates – with the exception of Gannon, who is hilarious dismissed with a typical flourish: “nothing useful vibrates in Craig’s upper storey”. Morrissey writes fondly about “signature Smiths’ powerhouse full-tilt”, or pauses during describing The Queen Is Dead sessions to comment admiringly that “Johnny is in the full vigour of his greatness”. Morrissey’s ire is directed – during the passages on the Smiths, at least – towards Geoff Travis, head of Rough Trade, who describes “How Soon Is Now?” as “just noise”. In fact, Morrissey is at his funniest when rounding on a slight, real or perhaps imagined. His first TV appearance finds him in the Green Room with George Best, before he is (in his opinion) rather rudely interviewed by Henry Kelly, “a little, pinched Irish madam… wearing a suit that looked better on the hanger.” Meanwhile, “local newshound” Anthony Wilson is another frequent target, a man who “assumed the cocogniscenti cloak and found himself blessed with the need to assess, judge and grade – like a war general plastered with rows of ribbons but who had never actually seen battle”. He is spectacularly catty about Sandie Shaw, referred to here as "the Duchess of Cumberland Place" or "the Dagenhall Doll". David Bowie "feeds on the blood of living mammals". The Smiths’ early success sees Morrissey taking up residence in Hornton Court in Kensington, where he receives visitors, some more welcome than others. Vanessa Redgrave arrives, “then goes on about social injustice in Namibia, and how we must all build a raft by late afternoon – preferably out of coconut matting.” Ann West and Winifred Johnson, whose children Lesley Ann and Keith were among the children abducted and killed by Ian Brady and Myra Hindley also pay a visit, and Morrissey responds warmly and with understandable sympathy. Later, he tells us why he elected to be known professionally by his surname - “Only classical composers were known by their surnames, which suited by mudlark temperament quite nicely” – and that Marr gave him his most famous nickname, after the press started referring him as 'miserable': “Johnny putters with ‘misery’ and playfully arrives at ‘misery Mozzery’, which truncates to Moz, and I am classified ever after.” Such japes and camaraderie – and the closeness Morrissey conspicuously felt to his bandmates – are thrown into some kind of relief towards the end of the section on the Smiths. Looking back, he writes, “At the hour of the Smiths birth, I had felt at the physical and emotional end of life. I had lost the ability to communicate and had been claimed by emotional oblivion.” Hang on. And then: “I became too despondent for anyone to cope with, and only my mother would take to me in understanding tones. Yet their comes a point where the suicidalist must shut it down if only in order to save face, otherwise you become a nightclub act minus the nightclub.” It’s an astonishing revelation: is Morrissey saying the Smiths saved him from suicide? Elswhere, the first American tour finds a dejected Morrissey in pre-gentrified Times Square, in “a quagmire of midnight cowboys and sterile cuckoos” while he becomes convinced that “the other three Smiths are taking steps to oust me”. At one point, Morrissey writes that he and Travis became locked in litigation of Hatful Of Hollow, which delays the release of The Queen Is Dead by nine months. The end comes almost without fanfare, following the sessions for the Strangeways, Here We Come. "It happened as quickly and as unemotionally as this sentence took to describe it.” With the Smiths over, you could be forgiven for thinking that Morrissey’s solo career – and his domestic life – would perhaps take centre stage. Alas, no. The 1996 court case, in which Mike Joyce claimed his 25%, occupies 40 pages. It is inevitably the saddest, angriest and most bitter part of the book; a far cry from the withering put-downs and dismissals dished out to Travis, Wilson, the Manchester Evening News or whoever else has crossed him. Morrissey reserves particular venom for presiding judge Weeks, “a bent little man with big eyes in a small face, an unfortunate vision that even his personal wealth cannot save.” Morrissey’s 2013 has been an extraordinary year, but for entirely the wrong reasons. He should have spent it celebrating 25 years as a solo artist – perhaps with a new album and maybe a deluxe edition box set collecting together his many solo hits. Instead, he has been blighted by health scares and cancelled tours. The will it/won’t it fuss surrounding the publication of Autobiography only seemed to suggest that Morrissey’s career was heading further off the rails. But then comes this: the book we (mostly) wanted it to be. It may not quite scale the lofty heights of David Niven's deathless The Moon's A Balloon - surely the benchmark for any aspiring autobiographer. And yet... Is there an audiobook for this, and will Morrissey read it? I'd pay again for that. Autobiography is sharply written, rich, clever, rancorous, puffed-up, tender, catty, windy, poetic, and frequently very, very funny. Welcome back, Morrissey. Follow me on Twitter @MichaelBonner.

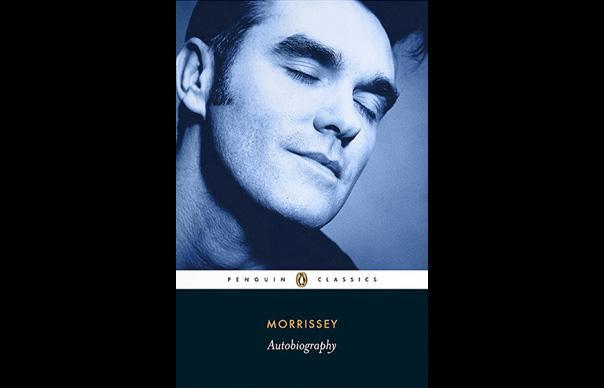

There are many revelations in Morrissey’s Autobiography, but perhaps the most unexpected arrives on page 194. “While in Denver,” writes Morrissey, “Johnny [Marr] and I attend a concert by A-ha, whom we have met previously and whom we quite like.”

In the weeks leading up to the release – at last! – of Autobiography, we have been bracing ourselves for possibility that he would – or more depressingly, wouldn’t – divulge many truths. About his sexuality, his relationship with his former Smiths bandmates, what he thinks of Bowie… Nothing, however, appeared to prepare us for the comprehensive nature of Morrissey’s disclosures in Autobiography. Look – here he is, turning down parts in EastEnders and Friends, contemplating fatherhood, being detained by Special Branch, telling us that he represented his school in the 100 and 400 metres. And some stuff about a guy called Jake.

As Dylan’s Chronicles or Neil Young’s Waging Heavy Peace have shown, it is possible for a musician writing an autobiography to successfully bypass niggly, pedantic details such as chronology, index and facts. Despite personally having little interest in great swathes of his solo career, the rock autobiography that’s given me most pleasure in the last few years has been Rod Stewart’s – simply because it satisfied the requirements of conventional storytelling.

One concern was that Morrissey might also ‘do a Dylan’ and opt for a strategy of obfuscation: ignore The Smiths, write round some other quite important things, spend a lot of time going into forensic detail about the recording of, say, Southpaw Grammar. Instead, what we have here is a very traditionally structured book that moves at a satisfying pace through Morrissey’s life and times, from his birth in “forgotten Victorian knife-plunging Manchester” up to December, 2011, with our hero about to leave Chicago after a rapturously received gig at the Congress Theater. At 457 pages, that works out at just over 8½ pages for every one of Morrissey’s 52 years. Though, of course, some years are bigger than others.

My overriding impression of Autobiography is the vividness of the detail. The bell that announces the end of the school day sounds at 3.40. With his Smiths advance from Rough Trade, he pays off a “lavish domestic phone bill of £80”. Ahead of their first Top Of The Pops appearance, the band are erroneously billed in The Sun as ‘Dismiss’. And so it goes. Such precise memories suggests Morrissey has been so profoundly affected by events that they have remained crystal-clear in his mind. Or perhaps he is a diligent archivist, with boxes full of clippings, cuttings and such ephemera. The book is littered with references and quotes from correspondence he’s received: among the most affecting are a letter from Johnny Marr after the Smiths split and a postcard from Kirsty MacColl that he receives weeks after her death.

The opening pages offer a fairly typical scene-setting: “Birds abstain from song in post-war industrial Manchester,” he writes, “where the 1960s will not swing, and where the locals are the opposite of worldly.” I’m reminded of Keith Richards’ Life, with its “landscapes of rubble, half a street’s disappeared… I couldn’t buy a bag of sweets until 1954”, a default setting for this kind of book. But Morrissey describes his childhood with a poet’s eye: “we are finely tailored flesh – good looking Irish trawling the slums of Moss Side and Hulme.” His descriptions of Manchester’s working class districts are profound and poetic; the passages that cover the depravations suffered by his own family often heartbreaking. The relocation of Nannie, his maternal grandmother “from Queen’s Square to a condemned house at 10 Trafalgar Square” captures the monstrous treatment of the working classes during the slum clearances. “Our lives are flattened before our eyes – as if the local council couldn’t wait a minute longer for we pack rats to gather our trappings and transistors.”

The opening sections of the book also detail his schooldays. His inquiry into the cruel discipline dished out by a headmaster (“What job did he think he was doing? And… for whom?”) or the sado-sexual behaviour of his PE teachers offers an insight into “the secret agony of a troubled child”. As he remarks, with a weight of sadness, “This is the Manchester school system of the 1960s, where sadness is habit forming.” This sadness dogs Morrissey for years to come.

His first gig is T.Rex at the Belle Vue on June 16, 1972, then Bowie – “every inch the eighth dimension”– at the Stretford Hardrock in September, Roxy Music two months later, where Morrissey speaks to Andy MacKay who’s pinball in the venue’s lobby. New York Dolls, Mott The Hoople, Lou Reed all follow. His prose captures the thrill of these formative musical encounters – a defining time in the life of the 12 year-old author. Roxy Music are “Agatha Christie queer,” he writes. It’s brilliant stuff.

Johnny Marr arrives on page 145. As Morrissey points out, they had met previously – “in the foyer of the Ardwick Apollo” at a Patti Smith gig. “I am shaken when I hear Johnny play guitar, because he is quite obviously gifted and almost unnaturally multi-talented.” In case you were wondering – and you probably are – Morrissey is extremely generous to Marr in the book – even after the Smiths’ split, when his emotional response to Marr veers from confusion to sadness. The Smiths section lasts 77 pages, from page 147 – 224; a good chunk – 16%, in fact – for what is essentially five years of his life.

What, then, do we learn about the Smiths? That Mike Joyce drum kit was called “Elsie”, that Mick Jagger came to see them live in New York and left after four songs, that Craig Gannon was “a fascinating bungle”. While writing about their time together, Morrissey is positive about his bandmates – with the exception of Gannon, who is hilarious dismissed with a typical flourish: “nothing useful vibrates in Craig’s upper storey”. Morrissey writes fondly about “signature Smiths’ powerhouse full-tilt”, or pauses during describing The Queen Is Dead sessions to comment admiringly that “Johnny is in the full vigour of his greatness”.

Morrissey’s ire is directed – during the passages on the Smiths, at least – towards Geoff Travis, head of Rough Trade, who describes “How Soon Is Now?” as “just noise”. In fact, Morrissey is at his funniest when rounding on a slight, real or perhaps imagined. His first TV appearance finds him in the Green Room with George Best, before he is (in his opinion) rather rudely interviewed by Henry Kelly, “a little, pinched Irish madam… wearing a suit that looked better on the hanger.” Meanwhile, “local newshound” Anthony Wilson is another frequent target, a man who “assumed the cocogniscenti cloak and found himself blessed with the need to assess, judge and grade – like a war general plastered with rows of ribbons but who had never actually seen battle”. He is spectacularly catty about Sandie Shaw, referred to here as “the Duchess of Cumberland Place” or “the Dagenhall Doll”. David Bowie “feeds on the blood of living mammals”.

The Smiths’ early success sees Morrissey taking up residence in Hornton Court in Kensington, where he receives visitors, some more welcome than others. Vanessa Redgrave arrives, “then goes on about social injustice in Namibia, and how we must all build a raft by late afternoon – preferably out of coconut matting.” Ann West and Winifred Johnson, whose children Lesley Ann and Keith were among the children abducted and killed by Ian Brady and Myra Hindley also pay a visit, and Morrissey responds warmly and with understandable sympathy.

Later, he tells us why he elected to be known professionally by his surname – “Only classical composers were known by their surnames, which suited by mudlark temperament quite nicely” – and that Marr gave him his most famous nickname, after the press started referring him as ‘miserable’: “Johnny putters with ‘misery’ and playfully arrives at ‘misery Mozzery’, which truncates to Moz, and I am classified ever after.”

Such japes and camaraderie – and the closeness Morrissey conspicuously felt to his bandmates – are thrown into some kind of relief towards the end of the section on the Smiths. Looking back, he writes, “At the hour of the Smiths birth, I had felt at the physical and emotional end of life. I had lost the ability to communicate and had been claimed by emotional oblivion.” Hang on. And then: “I became too despondent for anyone to cope with, and only my mother would take to me in understanding tones. Yet their comes a point where the suicidalist must shut it down if only in order to save face, otherwise you become a nightclub act minus the nightclub.” It’s an astonishing revelation: is Morrissey saying the Smiths saved him from suicide?

Elswhere, the first American tour finds a dejected Morrissey in pre-gentrified Times Square, in “a quagmire of midnight cowboys and sterile cuckoos” while he becomes convinced that “the other three Smiths are taking steps to oust me”. At one point, Morrissey writes that he and Travis became locked in litigation of Hatful Of Hollow, which delays the release of The Queen Is Dead by nine months.

The end comes almost without fanfare, following the sessions for the Strangeways, Here We Come. “It happened as quickly and as unemotionally as this sentence took to describe it.”

With the Smiths over, you could be forgiven for thinking that Morrissey’s solo career – and his domestic life – would perhaps take centre stage. Alas, no. The 1996 court case, in which Mike Joyce claimed his 25%, occupies 40 pages. It is inevitably the saddest, angriest and most bitter part of the book; a far cry from the withering put-downs and dismissals dished out to Travis, Wilson, the Manchester Evening News or whoever else has crossed him. Morrissey reserves particular venom for presiding judge Weeks, “a bent little man with big eyes in a small face, an unfortunate vision that even his personal wealth cannot save.”

Morrissey’s 2013 has been an extraordinary year, but for entirely the wrong reasons. He should have spent it celebrating 25 years as a solo artist – perhaps with a new album and maybe a deluxe edition box set collecting together his many solo hits. Instead, he has been blighted by health scares and cancelled tours. The will it/won’t it fuss surrounding the publication of Autobiography only seemed to suggest that Morrissey’s career was heading further off the rails. But then comes this: the book we (mostly) wanted it to be. It may not quite scale the lofty heights of David Niven’s deathless The Moon’s A Balloon – surely the benchmark for any aspiring autobiographer. And yet…

Is there an audiobook for this, and will Morrissey read it? I’d pay again for that. Autobiography is sharply written, rich, clever, rancorous, puffed-up, tender, catty, windy, poetic, and frequently very, very funny. Welcome back, Morrissey.

Follow me on Twitter @MichaelBonner.