‘‘I’ve done some research,” says Ashley Hutchings, rustling some sheets of paper excitedly. “It was a five-day event at the Roundhouse. Called ‘Circus Alpha Centauri’. December 20-24, 1967, and it was in aid of an arts centre. I was playing with Fairport…”

“Jimi Hendrix, as Father Christmas was compere… Obligatory lights and films…

“[Rustling] Tickets one pound!”

Hutchings is recounting the circumstances whereby, during a hairy psychedelic event in north London, he found himself with time on his hands.

“I was killing time, really,” says Hutchings. “Enjoying the music, and then I heard this sound… a single very tall, young person singing and playing the guitar. At that time, all the singer-songwriters, like John Martyn, sang with American accents. So to hear this very English-sounding music really stood out.”

Ashley Hutchings had just discovered Nick Drake. “We swapped phone numbers,” says Hutchings, “and as quick as possible I called Joe Boyd and said, ‘You’ve got to go and see this guy, he’s terrific. He’s very different.’”

Boyd heard a tape of demos that Drake had recorded while at Cambridge University, and immediately proposed making a record. “My first impression was that he was a genius,” he says. “It was that simple.”

To fully serve the material that Drake had, however, required sensitive treatment. For Boyd, the touchstones were George Martin’s string ensemble arrangements for The Beatles, John Simon’s involving production for Leonard Cohen’s Songs Of Leonard Cohen, and an assignment of his own – In My Life, the Judy Collins covers album he had lately produced for Elektra. It was all some distance from Boyd’s vérité production of the debut Incredible String Band album, a development which seems to have pleased Drake. “I said, ‘I hear strings’,” Boyd remembers. “He said, ‘Oh good.’ He was too shy to admit it, but he had already performed in that way at a May Ball in Cambridge.”

On the recommendation of Peter Asher, Boyd booked arranger du jour Richard Hewson to work on Drake’s material, and in a three-hour session at Sound Techniques, the musicians recorded Hewson’s treatments of “I Was Made To Love Magic” (oddly reminiscent of Moondog), “The Thoughts Of Mary Jane” (rather schmaltzy) and “Day Is Done” (heavily signposting the song’s crestfallen nature).

“We shook hands,” says Boyd, “and Nick and John Wood stood there and said, ‘That was a waste of money.’ I think Nick was relieved – he was hesitant to push his opinions forward too much, but he was stubborn.”

“They just didn’t seem to gel,” says John Wood, “with or without Nick’s parts. You could see Nick was getting more and more unhappy.”

To some eye-rolling from Boyd and Wood, Drake then suggested a friend from Cambridge “whose arrangements aren’t too bad”. “We looked at each other in a fairly jaded fashion,” remembers John Wood. “Then Robert Kirby turns up with a double string quartet and knocks off two tunes in an afternoon.”

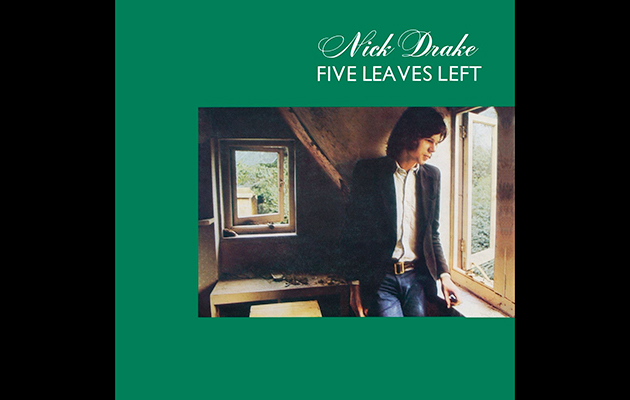

“We made Five Leaves Left in bits and pieces,” says Joe Boyd. “I was busy with a lot of other things, so it was, ‘OK, I have a few days here, let’s do some Nick Drake sessions.’ And then two months later we’d do more. Each track was thought about and we decided what the best lineup would be for that.”

Additional players were slowly drawn into the record’s inner circle. Cellist Clare Lowther played on “Cello Song”. Bassist Danny Thompson, in company with ubiquitous 1960s percussionist Rocky Dzidzornu, made explicit the driving urgency in “Three Hours”. American pianist Paul Harris, who had been musical director on John and Beverley Martyn’s Stormbringer!, played on “Man In A Shed” and “Time Has Told Me”. The latter also featured Richard Thompson.

“Nick was a very original player,” says Thompson. “He spent a lot of time on his songs, on the accompaniments to them, figuring out what he was going to do. He does some fairly unusual things. He does things a bit back to front sometimes – I think you only do that by thinking very hard about what you’re doing, embedding things so they become second nature.

“‘Time Has Told Me’ changes shape harmonically. It took me a while to figure it out – he had more of a jazz ear than a folk ear. It seemed to go to places people hadn’t gone before.”

“I’m always amused when I go into a big record store and see Nick Drake filed under ‘folk’,” says Joe Boyd. “If there’s ever anyone who wasn’t folk, it’s Nick Drake.”