Nearly a year later, John Wood answered the telephone to Nick Drake. Drake would occasionally drop in to visit John and Beverley Martyn at their new home in Hastings, on the Sussex coast, and visit Wood and his family at their home in Suffolk, but otherwise, his movements were sketchy. Wood hadn’t heard from him, he remembers, for “a long time”, but when the pair spoke, it appeared that Drake’s appetite for recording was undiminished.

“He said, ‘I’m ready to go back in the studio. When can I come in and record?’” says Wood. Sound Techniques remained a busy studio, but something about Drake’s increasingly mercurial nature motivated Wood to suggest he came in as soon as possible.

“He was off the radar a bit,” says Wood, “so I thought maybe I shouldn’t hang about. The only time we could get was in the middle of the night. I just felt he wanted to get on with it quickly. There wasn’t any messing about – he knew exactly what he wanted to do.”

What was recorded over those two evenings became 1972’s 28-minute Pink Moon. “The first or second thing we put down was ‘Parasite’,” says Wood. “But at that point I’m not sure if I knew what was going on. I remember saying, ‘Do you want Danny to come in?’ and he just said, ‘No, I don’t want anyone else on it.’”

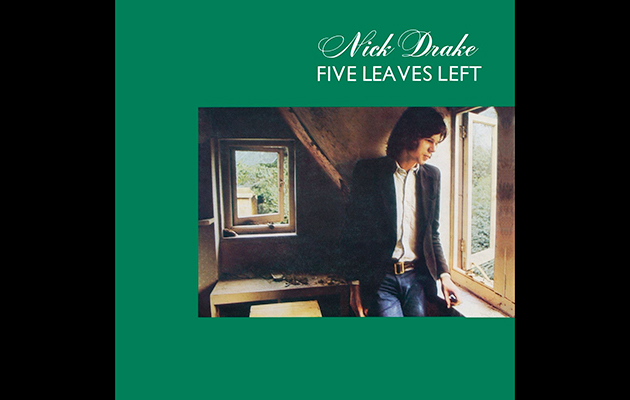

Among the material Drake recorded was a song whose complex minor-chording creates a sense of stillness, while describing a world of unrelenting motion. It sounded of a piece with material from Five Leaves Left. This, finally, was “Things Behind The Sun” – “that song”, the song that Drake had played as an encore at the Royal Festival Hall two years earlier.

“One of the interesting things about Nick,” says John Wood, “is that he pretty much always knew what he was going to do with everything.”

In the title track, Robin Frederick hears a musical statement of Nick Drake’s personal condition. “When he goes down to that low note, it’s too low for him to sing,” she says. “He could easily have put it up a step and sung it that way, but he wanted it like that. I trust the choices he made. That low note is basically saying, ‘I can’t get any lower – this is too low for me.’”

Pink Moon was Drake’s final album. He died on November 25, 1974.

It was around 1978, thinks Joe Boyd, when they started turning up at his house. “Kids from Ohio, with backpacks. ‘You knew Nick Drake? Please tell me about him.’ How they knew where I lived, I don’t know, but I got people knocking at my door.”

Once the manager/producer of a struggling songwriter, since Nick Drake’s death Boyd has been cast by some as custodian of Drake’s fortunes in life – implicitly saying that if different decisions had been made about his music, the outcome of his life would have somehow been different.

“There is a school of thought which says Nick Drake is at his best at his purest, ie Pink Moon, and all the rest is just Joe Boyd imposing something on Nick,” says Boyd. “But I would say to them: that was what he wanted. The only time he performed in Cambridge was with a string quartet. Before I even met Nick, he was working with Robert.

“I hear from people who ask, ‘When are you going to put out the version of Five Leaves Left or Bryter Layter with just Nick’s voice and guitar?’ And I write them a polite note saying, basically, fuck off. Explaining that it’s recorded live in the studio… The only way you get ‘River Man’ to sound like that is to put Nick in the middle of the strings – you can’t get an album of just Nick and guitar because the strings are all over the voice track.”

In their son’s final months, Boyd also retained the confidence of Nick Drake’s parents, who asked him to call and reassure Nick that he wouldn’t think less of him if he took antidepressants. Beyond that, Boyd has looked after Drake by making sure his records have remained available in perpetuity.

“I knew Chris Blackwell would always support Nick,” Boyd remembers, “but I said ‘Who knows, you might get run over by a bus tomorrow. I want it in the contract that his records don’t go out of print.’” I had the feeling that one day people would get it, but not if the records had been allowed to disappear.”

When they arrived at Boyd’s door, these kids from Ohio generally told Joe the same story.

“Both boys and girls would tell it,” says Boyd. “‘I started going out with this person, it was early in the relationship and it was starting to get serious. They said, “Do you know Nick Drake?” I said, “No. Who’s Nick Drake?” and they said: “Sit down…”

“‘And they put this record on, and something became clear to me that if I didn’t take this seriously, then the relationship didn’t have a chance.’”