A couple of months ago, I was staying with an old friend, whose teenage daughter was heading out to an ‘80s movie all-nighter. Before she went, she listed what they were going to watch; Pretty In Pink, Ferris Bueller’s Day Off – the kind of John Hughes films that are now routinely used as exemplars of that decade. Her father and I were talking, and we realised we hadn’t actually seen any of them. A week or two later, my eight-year-old went to a birthday party at a roller disco in South London. The theme was, again, the 1980s, and he came home with Day-Glo wristbands. And again, I was left somewhat in the dark: my 1980s were spent at school and university, and none of these things really mattered to me. It would be easy, and probably accurate, to see these gaps in my adolescence as evidence, maybe, of a certain cultural snobbery, though a diet of The Smiths, Pixies, Sonic Youth and The Go-Betweens, of Martin Scorsese, Bill Forsyth, Steve Martin and all those foreign-language student-bait movies of the time (Betty Blue, Diva, Wings Of Desire) doesn’t seem particularly elitist or transgressive this far down the line. Most of those records and films have become to some degree canonical (or were canonical, for a while at least). Reminiscences and reconstructions of the 1980s, though, often tend to fixate on a more reductive set of signifiers: synthpop, neon, gated reverb, conspicuous consumption. It’s this world that Daft Punk’s much-discussed “Random Access Memories” seems to emerge from; a late ‘70s/early ‘80s milieu of Hollywood superstudios, an aesthetic universe which seemed anathema to a teenager schooled in indie culture, notwithstanding the mediated eclecticism of the NME (at 17, I had an improbable number of Courtney Pine and Andy Sheppard records). One of the things that, I hope, a long career as a music journalist encourages is an unsentimental perspective on the records of your past: just because I thought “George Best” was some sort of masterpiece in 1987 doesn’t mean I’ve had the slightest urge to play it for over 20 years; I don’t look back with much pride on my early journalistic boostering for The Frank & Walters, at the tip of a distressingly large iceberg. Tastes change; that’s OK. Most of my positive musical responses aren’t dictated by nostalgia, otherwise I’d be playing Showaddywaddy’s “Under The Moon Of Love” more than something else from 1974 like, say, “Court And Spark”. Salient to today, it took me a long time to appreciate The Doors, chiefly because I so thoroughly disliked the people who were into them at college. Some prejudices, though, remain tough to budge, and while the brilliance of Chic and Giorgio Moroder might have been personally understood and accepted a long time ago (I’m not convinced I have anything to add to discussions about the excellence of “Giorgio By Moroder” and “Get Lucky”, other than to restate that, for all their obvious influences, they are steely but idiosyncratic hybrid beasts rather than precise facsimiles), there are textures on “Random Access Memories” that set off a few alarms. It is simpler, it transpires, to grow out of C86 than it is to grow into soft-rock. “Touch”, for all the critical anxiety targeted towards it, isn’t so much of a problem for me, beyond Paul Williams’ brief and histrionic vocal interludes: much of it reminds me, serendipitously, of something by Air, polished to an even greater and more ethereal degree. I love the jazz interlude, too, possibly because it recalls something I do remember from those ‘80s with a degree of fondness; Ze Records, and August Darnell. The bigger problems come in some of those ballads like “The Game Of Love” and “Within”, that seem infused with what hipper music journalists than I often call Yacht Rock; that luxe ‘80s AOR promulgated by the likes of Christopher Cross and Michael McDonald; the power ballads without the power. I’ve seen a good few comparisons between these tracks and Steely Dan (a band, contrarily, I’ve always loved; evidence, I guess, that there are always glitches and inconsistencies in your personal aesthetics, no matter how scrupulously hardline you perceive yourself to be). Apart from a bit of “Beyond” and “Fragments Of Time”, though, I don’t really see the similarity. Steely Dan’s music might have always been smooth, but it also had an edge, a fastidiously-managed jumpiness that seemed to reflect the snark of the lyrics. One of the defining elements of “Random Access Memories” is its phenomenal lack of snark; Chilly Gonzales’ piano line on “Within” attracts a vocabulary that would have never suited Steely Dan: “plangent”, “lachrymose”, “earnest”. And maybe this is the key to coming to terms with Daft Punk’s re-imagining and repurposing of the 1980s: that unlike so many of their contemporaries (and unlike a good few other projects involving Gonzales, come to think of it), they appear completely untainted by irony. I’m wary of suggesting that their earnestness somehow makes their music more “real” and “authentic”, since those labels appear less relevant than ever to a meticulous audio confection like “Random Access Memories”. Nevertheless, there’s something about listening to “Random Access Memories” that feels less like eavesdropping on an in-joke than most records which root themselves in this particular 1980s. Maybe that, as well as the insidious power of the tunes, is what is making it such a success. And maybe it’s that which makes it a more rewarding album with each listen: one which takes itself, and a culture of uninhibited decadence, with an uncommon degree of seriousness. I’m glad, incidentally, that I didn’t try writing this piece a week ago. With multiple listens, a core value of “Random Access Memories” presents itself: those uncomfortable sounds and textures and references remain, but the turnover of ideas is so slick and fast that there’s always something interesting and stimulating and exciting just round the corner. I hope I’m not one of those music journalists who disdain and dismiss snap judgments; they’re an integral part of the pleasure of responding to records, and it’s somewhat disingenuous of some music journalists to imply that all album reviews are – or need to be - crafted after a dozen-plus close listens. Nevertheless, for all its high-concept 21st Century unveiling, “Random Access Memories” is built on a classic old conceit: the most immediate of singles, ushering in an album which repays deep listens. Free streaming might encourage the world to play it once and leap to their conclusions, but it also means that millions can get used to its idiosyncracies, warm to them, before they buy. It’s worked, and it’s an increasingly fine album. Oh, and the drums are the best bit. Follow me on Twitter: www.twitter.com/JohnRMulvey

A couple of months ago, I was staying with an old friend, whose teenage daughter was heading out to an ‘80s movie all-nighter. Before she went, she listed what they were going to watch; Pretty In Pink, Ferris Bueller’s Day Off – the kind of John Hughes films that are now routinely used as exemplars of that decade. Her father and I were talking, and we realised we hadn’t actually seen any of them.

A week or two later, my eight-year-old went to a birthday party at a roller disco in South London. The theme was, again, the 1980s, and he came home with Day-Glo wristbands. And again, I was left somewhat in the dark: my 1980s were spent at school and university, and none of these things really mattered to me.

It would be easy, and probably accurate, to see these gaps in my adolescence as evidence, maybe, of a certain cultural snobbery, though a diet of The Smiths, Pixies, Sonic Youth and The Go-Betweens, of Martin Scorsese, Bill Forsyth, Steve Martin and all those foreign-language student-bait movies of the time (Betty Blue, Diva, Wings Of Desire) doesn’t seem particularly elitist or transgressive this far down the line. Most of those records and films have become to some degree canonical (or were canonical, for a while at least). Reminiscences and reconstructions of the 1980s, though, often tend to fixate on a more reductive set of signifiers: synthpop, neon, gated reverb, conspicuous consumption.

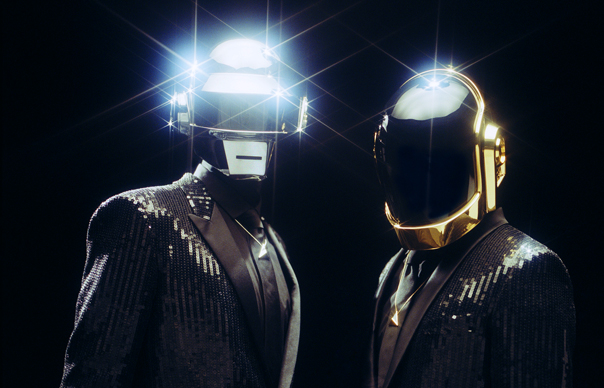

It’s this world that Daft Punk’s much-discussed “Random Access Memories” seems to emerge from; a late ‘70s/early ‘80s milieu of Hollywood superstudios, an aesthetic universe which seemed anathema to a teenager schooled in indie culture, notwithstanding the mediated eclecticism of the NME (at 17, I had an improbable number of Courtney Pine and Andy Sheppard records).

One of the things that, I hope, a long career as a music journalist encourages is an unsentimental perspective on the records of your past: just because I thought “George Best” was some sort of masterpiece in 1987 doesn’t mean I’ve had the slightest urge to play it for over 20 years; I don’t look back with much pride on my early journalistic boostering for The Frank & Walters, at the tip of a distressingly large iceberg. Tastes change; that’s OK. Most of my positive musical responses aren’t dictated by nostalgia, otherwise I’d be playing Showaddywaddy’s “Under The Moon Of Love” more than something else from 1974 like, say, “Court And Spark”. Salient to today, it took me a long time to appreciate The Doors, chiefly because I so thoroughly disliked the people who were into them at college.

Some prejudices, though, remain tough to budge, and while the brilliance of Chic and Giorgio Moroder might have been personally understood and accepted a long time ago (I’m not convinced I have anything to add to discussions about the excellence of “Giorgio By Moroder” and “Get Lucky”, other than to restate that, for all their obvious influences, they are steely but idiosyncratic hybrid beasts rather than precise facsimiles), there are textures on “Random Access Memories” that set off a few alarms. It is simpler, it transpires, to grow out of C86 than it is to grow into soft-rock.

“Touch”, for all the critical anxiety targeted towards it, isn’t so much of a problem for me, beyond Paul Williams’ brief and histrionic vocal interludes: much of it reminds me, serendipitously, of something by Air, polished to an even greater and more ethereal degree. I love the jazz interlude, too, possibly because it recalls something I do remember from those ‘80s with a degree of fondness; Ze Records, and August Darnell.

The bigger problems come in some of those ballads like “The Game Of Love” and “Within”, that seem infused with what hipper music journalists than I often call Yacht Rock; that luxe ‘80s AOR promulgated by the likes of Christopher Cross and Michael McDonald; the power ballads without the power. I’ve seen a good few comparisons between these tracks and Steely Dan (a band, contrarily, I’ve always loved; evidence, I guess, that there are always glitches and inconsistencies in your personal aesthetics, no matter how scrupulously hardline you perceive yourself to be).

Apart from a bit of “Beyond” and “Fragments Of Time”, though, I don’t really see the similarity. Steely Dan’s music might have always been smooth, but it also had an edge, a fastidiously-managed jumpiness that seemed to reflect the snark of the lyrics. One of the defining elements of “Random Access Memories” is its phenomenal lack of snark; Chilly Gonzales’ piano line on “Within” attracts a vocabulary that would have never suited Steely Dan: “plangent”, “lachrymose”, “earnest”.

And maybe this is the key to coming to terms with Daft Punk’s re-imagining and repurposing of the 1980s: that unlike so many of their contemporaries (and unlike a good few other projects involving Gonzales, come to think of it), they appear completely untainted by irony. I’m wary of suggesting that their earnestness somehow makes their music more “real” and “authentic”, since those labels appear less relevant than ever to a meticulous audio confection like “Random Access Memories”.

Nevertheless, there’s something about listening to “Random Access Memories” that feels less like eavesdropping on an in-joke than most records which root themselves in this particular 1980s. Maybe that, as well as the insidious power of the tunes, is what is making it such a success. And maybe it’s that which makes it a more rewarding album with each listen: one which takes itself, and a culture of uninhibited decadence, with an uncommon degree of seriousness.

I’m glad, incidentally, that I didn’t try writing this piece a week ago. With multiple listens, a core value of “Random Access Memories” presents itself: those uncomfortable sounds and textures and references remain, but the turnover of ideas is so slick and fast that there’s always something interesting and stimulating and exciting just round the corner. I hope I’m not one of those music journalists who disdain and dismiss snap judgments; they’re an integral part of the pleasure of responding to records, and it’s somewhat disingenuous of some music journalists to imply that all album reviews are – or need to be – crafted after a dozen-plus close listens.

Nevertheless, for all its high-concept 21st Century unveiling, “Random Access Memories” is built on a classic old conceit: the most immediate of singles, ushering in an album which repays deep listens. Free streaming might encourage the world to play it once and leap to their conclusions, but it also means that millions can get used to its idiosyncracies, warm to them, before they buy. It’s worked, and it’s an increasingly fine album.

Oh, and the drums are the best bit.

Follow me on Twitter: www.twitter.com/JohnRMulvey