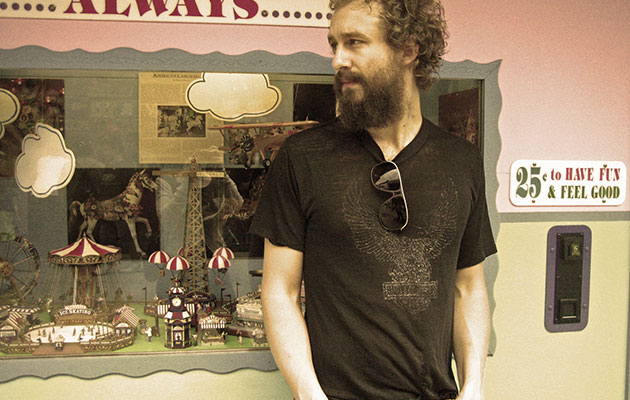

You have seen pictures of him in which he has something of the look of a desert ascetic, a fuzzy hippy mystic prone to peyote visions, a great deal of staring into diminishing space and conversations with cooing seraphim. Today, though, he just

looks fucked. “Band practice,” he says by way of explanation. “One thing led to another and didn’t stop there.”

It’s a Sunday afternoon towards the end of January. New York’s light is already paling. Houck meets Uncut at Electric Lady, the studio built by Jimi Hendrix at 52 West 8th Street, in Greenwich Village, where Houck came to mix three of the tracks for Muchacho. There are portraits of Jimi on the walls of the stairwell leading down from a somewhat scruffy ground floor reception area, accessed directly from the street through a door you have to use a shoulder to open, Jimi in his braided military tunic, a stoned hussar. There are psychedelic murals by Lance Jost on the walls of the long corridor that leads to the studio where Hendrix recorded and once held court. The room we are standing in feels spacious, though it’s not large. Various instruments are scattered, although not untidily, around its curved perimeter. The atmosphere here is lulling. Hush prevails.

There’s another studio upstairs, where someone is currently recording, no-one’s sure who. Their session means Houck can’t show me as planned the vintage desk he used to mix the tracks he brought here and no doubt explain its many intricacies. I try manfully to hide my disappointment and perk up noticeably when a drink is suggested.

We walk some distance to the East Village, across Broadway and Lafayette Street and down Great Jones Street, to the Bowery Hotel, into whose murky opulence we enter rather expecting to be turned away. The lobby and lounge through which we walk to the bar are low-ceilinged, sturdy beams above us, wood-panelling on the walls, thick ornamental carpets and rugs throughout. In bygone times, you can imagine it as a regular haunt for bootleggers, the occasional gangster and people otherwise perched unsteadily on the legal rim of things, their money made from not always legitimate activities.

Drinks are duly ordered and Houck is soon being served Johnnie Walker Black, on the rocks, in a glass big enough to hold a fair amount of the bottle the whiskey was poured from. The beer Matthew has ordered as a chaser seems highly irrelevant. A woman sitting nearby with hair that looks like the stuffing pouring out of a toy lion torn open by a laughing cat is talking in a voice that sounds like a chainsaw howling through teak, shrill chums providing a caterwauling chorus. I’m relieved when the shrieking coven ups and leaves in a swirl of scarves, drapes and wraps, leaving behind them a trail of perfume that makes me cough like a Tommy in a Flanders trench, choking on mustard gas.

At least now, thankfully, I can hear Houck, whose voice is for the most part pitched not much higher than a whisper. He’s telling me, I can now be sure, about growing up in a place called Toney, in northwestern Alabama.

“It had a population of 600 people,” he says. “It was real small. It’s not even really a place. It’s just a piece of land. There’s no town as such. I don’t know how growing up there affected me or shaped my personality. I had nothing to compare it to. I’d never been anywhere else. It’s where I lived. As far as I knew, it was no different to anyplace else. I didn’t grow up feeling especially isolated, although I guess that’s what we were. I don’t know if I’d be any different if I was from somewhere else.”

When he mentions that his grandfather was a preacher, I’m just about to pursue a connection to songs on early Phosphorescent albums – I’m thinking of the eerie raptur of something like “My Dove, My Lamb” or the congregational sing-along of “Last Of The Hand-Me-Downs”, the Pentecostal horns that pepper his records – when he heads me off, with another laugh.

“This wasn’t like something out of Flannery O’Connor or There Will Be Blood,” he says. “There were no rattlesnakes or speaking in tongues. It was definitely not a Southern revivalist church thing at all. There was none of that hysteria. It was much more straitlaced, pious. Very respectful and the hymns were beautiful. That’s the connection, the hymnal quality. That’s certainly a part of a lot of my music. I’ve always loved that hymn-like stuff.”

By the age of eight, he’d moved with his family to the larger Alabama city of Huntsville, in the Tennessee River Valley. Music became a central focus of his teenage life, the usual stuff on the radio that anyone his age would have listened to, mostly hard rock and mainstream country, although he would develop a taste for the harder outlaw country of Willie Nelson and Waylon Jennings. Nirvana were an early inspiration and you can distantly hear echoes of their signature thrum on a track like “You” from Hipolit, the self-released album Houck put out under the name Fillup Shack in 2000, although perhaps more typical of his music at the time is a song like “Down Roads”, which is reminiscent of Village-era Bob Dylan and sounds like it was recorded on someone’s back porch.

He was living by then in Athens, GA. Local label Warm put out a second album, A Hundred Times Or More. Its often rickety country-folk recalled Will Oldham, whose influence prevailed on 2005’s Aw Come Aw Wry, released by the Ohio-based Misra label, which also on stand-out tracks like “Joe Tex, These Taming Blues” introduced Stax horns to the mix and further embraced elements of gospel and Southern soul. When Misra label manager Phil Waldorf left to launch Dead Oceans in 2007, Houck was one of his first signings. “I’ve known Matthew for nearly a decade,” Waldorf tells Uncut. “It was a relationship I wanted to continue when we formed Dead Oceans. He’s making important, timeless albums, the kind of records that fans of great songwriters cherish forever. That’s why we want to be involved with someone like him.”