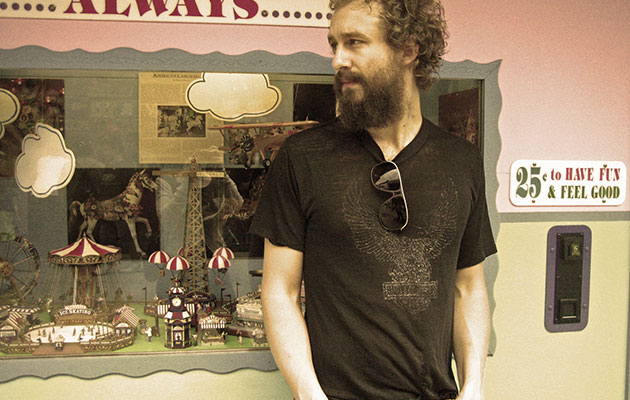

Order the latest issue of Uncut online and have it sent to your home – with no delivery charge! Matthew Houck’s quietly brilliant career fronting PHOSPHORESCENT has taken him from Alabama to Brooklyn and encompassed cosmic outlaw country, Crazy Horse jams, electronic washes and an ambition to m...

But now it’s here, an album, as Matthew Houck describes it, of reckoning and redemption, about walking out of darkness into light. For a record that took eventual shape from bleak beginnings, Muchacho sounds often euphoric, giddily resplendent. Musically, it’s the most expansive album Houck’s yet made. The cunnilingual swirl of Mariachi horns melts into hazy clouds of synthesisers, strings cascade, at least once making you think of Astral Weeks. Scott Stapleton and Ricky Ray Jackson from his touring band provide spectacular piano and pedal steel parts and Bobby Hawk’s fiddle is often sensationally deployed. Houck’s voice soars, rising on thermal drafts.

The lyrics typically are hallucinatory, visionary, by turns specific and oblique, like extracts from half-remembered dreams, endlessly revealing. Even as they appear to be giving nothing away, they tell you somehow everything. Houck baulks, though, visibly bristles, in fact, at the thought they will be taken as wholly autobiographical.

“They are first and foremost songs,” he says. “There’s a craft to songwriting and I think I’ve worked at it hard and long enough to be pretty good at it on occasions. You’re not just offering up the details of your life and what’s happening in it, like the pages of a diary or something. I mean, I haven’t just made a Joni Mitchell record.”

To what extent, though, do your songs feed off the specific traumas of your own life? “I’m always hesitant about going too deeply into this,” he says, a little uncomfortably. “Yes, there are specific events that were the catalyst for this record. But that doesn’t mean those events are the lifeblood of the songs. The songs and music exist independently of the things that may have given life to them. And while a certain amount of trauma was the catalyst for the album, trauma isn’t the record’s overarching theme. It was equally born out of ecstatic joy, my own failings and just the dumb shit I’ve done.

“There’s also a healthy dose of fiction in there,” he continues. “That shouldn’t be overlooked. I was reading an old interview with Warren Zevon and he made the point that songwriters are judged differently to other artists, filmmakers and novelists, for instance. It’s like there’s a different set of critical criteria. Songwriters are scrutinised in a different way. As a songwriter you end up being totally identified with your songs and what they say. You’re almost expected to write only about the things that happen to you, as if that will somehow make the songs somehow more ‘true’. It’s like everything you write has to be confessional, based on the specifics of your life. I’ve always wanted, and want still, to enjoy greater freedom as a writer than that.

“I think it was [American poet] Wallace Stevens who said something like the deeper you go into the personal, somehow the more universal all of a sudden something will become. The other argument is, open something up vaguely and that’s where the universality is. I don’t know which is most true. When I’m being specific in a song, I’m hyper-aware of what I’m doing it and it scares me. I don’t like to do that. But sometimes you have to. There’s no other way. But then you end up with a reputation for brooding and introversion or whatever and that’s who people start to think you are. They can’t separate you from the songs.

“I was talking to someone about ‘A New Anhedonia’, from the new record,” he says. “And I explained that ‘anhedonia’ means the lack of being able to experience pleasure in things that should be pleasurable, losing the ability to take pleasure in something that was innately pleasurable or had been previously. All of a sudden things you would normally lean on hard to get out of a funk, all of a sudden those things disappear. The song asks what is there left when all these things fall away? What have you got? What are you left with? Sometimes it’s not much.

“And he said, ‘But on the cover of the album [a rather racy shot of Houck in what looks like a hotel room with a couple of scantily clad beauties on the bed behind him] you’re laughing!’ That I looked happy in the picture was confusing to him. But I am usually happy. I’m not a wreck of humanity. I could see how you could think that if you had only some of the songs to go on, but they’re just part of the picture. He couldn’t understand the song came from a place I was in when I wrote it,” Houck goes on. “But I came back, you know?”