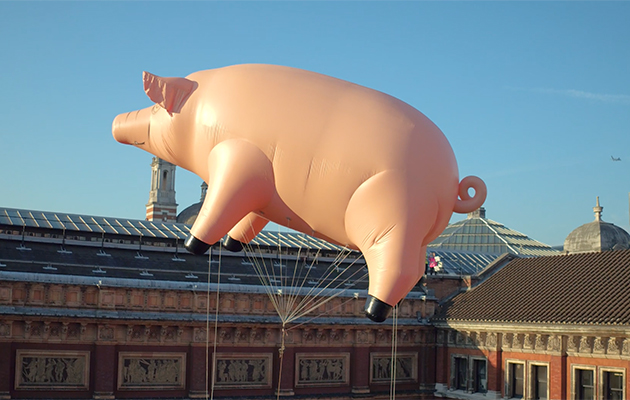

Among the official merchandise available at Pink Floyd: Their Mortal Remains visitors can buy a tote bag featuring a sketch of a pig flying over the roof of the Victoria & Albert Museum. The image says a lot about the exhibition and the band it documents: a peculiarly English exploration of cult...

Among the official merchandise available at Pink Floyd: Their Mortal Remains visitors can buy a tote bag featuring a sketch of a pig flying over the roof of the Victoria & Albert Museum. The image says a lot about the exhibition and the band it documents: a peculiarly English exploration of culture, design and innovation. You can see it in artefacts like the Azimuth Co-Ordinator – a rectangular box used to control a quadraphonic sound system – or the remarkable technology used to animate a 3D hologram replica of the Dark Side Of The Moon light prism. Pink Floyd, the exhibition concludes, is not just the work of musicians – but also architects, illustrators and technical engineers. The visionary eccentricity of Pink Floyd may not have happened without them.

Following on from David Bowie Is – also at the V&A – and the Rolling Stones’ Exhibitionism, Pink Floyd: Their Mortal Remains similarly tells the band’s story through a mix of paraphernalia, gadgetry and film. The most interesting, perhaps, is the first. The cane used on Waters during his school days, a hand-written letter from Syd Barrett to girlfriend Jenny Spires, the page from Nick Mason’s 1968 diary, a 1975 tour rider (including “six hundred lbs of dry ice for each performance”), the Polaroid of Barrett from July 1975 when he arrived unannounced at Abbey Road during the sessions for Wish You Were Here. Meanwhile, gear like the Binson Echorec Baby – a delay system used by Barrett that looks like a prop from a 1960s episode of Doctor Who – is wonderfully Heath Robinson. Look up, or you might miss Barrett’s red bicycle suspended from the ceiling.

Inevitably, the earlier years feel the richest. The wonderful poster art for the UFO Club, IT magazine front covers and early Floyd rave-ups sets the bar very high. Commendably, the band’s formative history is remarkably well-preserved – there is a 1965 concert bill, two contracts for BBC sessions, acetates and tapes. Among the most historically puissant is a contract for a BBC Radio Top Gear programme with Barrett’s name crossed out and ‘David Gilmour’ hand-written in.

The scale of the exhibition blossoms as the Seventies’ progress. One room is devoted to breathtaking large-scale images taken during the Wish You Were Here cover shoot, another includes a giant Battersea Power Station, while another contains the two giant metal heads used on the Division Bell cover. They are undoubtedly impressive, but arguably they lack the textural warmth and intimacy of the early clobber. The through-line they present, though, is unquestionable. In 1967, Barrett told Melody Maker, “We feel that in the future, groups are going to have to offer much more than just a pop show. They’ll have to offer a well-presented theatre show.” For Floyd, the concept of a “well-presented theatre show” enlarged as the decades passed, as witnessed here by flying pigs, replica Spitfires and ever more elaborate stage props.

Aside from the band’s creative and technical achievements, the central notion presented here is one of harmony. Viewers will enjoy Gilmour and Roger Waters – filmed separately – warmly praising the other’s contributions to writing “Wish You Were Here”. The departures of both Barrett and Waters, along with Richard Wright’s enforced hiatus during the early Eighties, are discretely handled. A final room features the band’s Live8 reunion as a 360° experience – all good vibes and hugs.

For those who wonder whether this is a final, salutary hurrah to the band’s 50 years might do well to examine the Floyd family tree at the very start of the exhibition. At the end of a labyrinthine list that includes the Tea Set, Sigma 6 and other obscure names from the band’s pre-history sits the latest entry. It reads, “Pink Floyd 2008 – Present”. Maybe there’s some life still in these mortal remains, after all.

Follow me on Twitter @MichaelBonner