Twenty-five years ago, Prince knew he was a genius. The rest of the world, however, needed a little convincing. How to change this? Teach your band and friends how to act, hire a rookie director who can “tell my life story in 10 minutes”, and convince Hollywood to bankroll a musical. The result...

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qsdR8eycRys

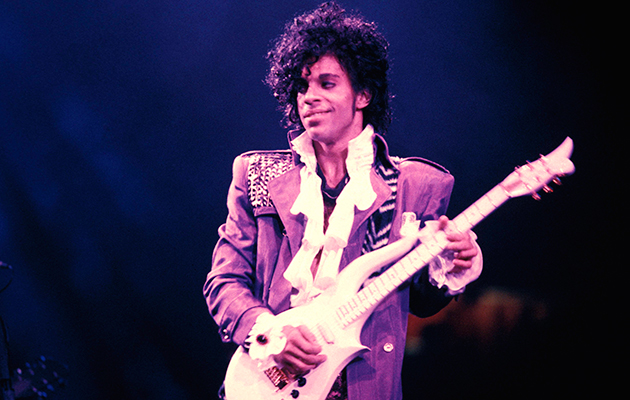

Read any description of Purple Rain – and the words that appear most often are “biggest”, “bestselling”, “breakthrough” and “phenomenon”. It’s ironic, then, that this dual blockbuster, which made Prince a world-famous actor and musician, began life as a film that nobody wanted to finance or direct. The film would go on to gross $70 million, leaving executives at Warner Bros (who had been reluctant investors) stunned. The album, meanwhile, featuring several classic singles (“When Doves Cry”, “Let’s Go Crazy”, “Purple Rain”), topped the US album charts for 24 consecutive weeks. In Britain, it catapulted Prince from cult status to superstardom.

“Purple Rain really put the spotlight on Prince,” notes Matt Fink, former keyboard player in his band The Revolution. “A lot of people became aware of him very quickly. ‘You gotta go see this movie.’ ‘Oh yeah, I’ve heard of him… maybe I should check it out.’ Suddenly those people were finding out what all the fuss was about.” And then, in perfect symmetry, they bought the soundtrack album – which sold 10 million. “You couldn’t release enough singles from it,” Leeds marvels. “Everyone was discovering this spectacular performer and going wild for him.”

But when Bob Cavallo began his search for writers and directors in 1983, Warner Bros (the studio affiliated to Prince’s label) informed him it had no wish to spend money on a Prince movie. Cavallo and his partner Joe Ruffalo decided to go it alone. They approached an experienced Hollywood screenwriter, William Blinn, creator of Starsky & Hutch. Blinn was 46, and by his own admission “as square a white man as you’re going to find”. But he met Prince in LA, liked his ideas and agreed to pen a script.

“I suspect I was hired because I was executive-producing a television series called Fame,” Blinn relates. “I was the only guy in town doing something that combined music and drama. [Prince] talked to me about the kind of movie he wanted to do. He had a rough outline. It had the dysfunctional family and the rivalry between the two bands.”

The singers and musicians in Prince’s burgeoning Minneapolis funk-pop empire embarked on a two-month regime of acting and dancing lessons. They included Morris Day, frontman of The Time (a Prince-produced project); and Vanity, Prince’s ex, who performed in the provocative Vanity 6. Morris Day and Vanity were to be Purple Rain’s comic relief and romantic lead, respectively. There would also be cameos for The Revolution. Some of their interplay with Prince (The Kid) would be uncannily true-to-life.

“The movie exaggerated the rivalry between The Revolution and The Time,” Alan Leeds points out, “but it’s certainly true that there were frustrations in Prince’s band – in all the bands – that he didn’t allow them creative input. He was rigid in his assignment of their wardrobe, their make-up, their hairstyles. It was unsettling to know that he could change the way they looked, just like that, and they had no voice in it. But Prince’s rationale was, ‘I’m making you a star. Shut the fuck up.’”

The Revolution had undergone a personnel change. Guitarist Dez Dickerson had left after the ‘Triple Threat Tour’ and been replaced by 19-year-old Wendy Melvoin, the lover of keyboard player Lisa Coleman. Melvoin debuted with The Revolution at Minneapolis’ First Avenue club on August 3, 1983. The concert, a benefit for a local dance theatre, was a chance for Prince’s fans to hear the new music he’d been composing. “There was real fascination from the crowd that night,” remembers Leeds. “People were staring at the stage with their jaws dropped. It was clear that the music, the band, everything about this, was a step forward from six months ago.”

The script had not escaped criticism. A series of directors turned it down, declaring it too dark. The Kid’s father committed suicide. The Kid himself had suicidal thoughts. There wasn’t much music. Albert Magnoli, a 28-year-old who had edited the teen movie Reckless, told Bob Cavallo he wanted to write a new screenplay, which he would then direct. With no other option, Cavallo decided to take the risk. (“I thought, we’re gonna roll the dice here. Everybody will be new. First-time actors. First-time producers. First-time director.”) But when Magnoli flew to Minneapolis to discuss his ideas, he realised Prince was only interested in filming the old script. Magnoli told him it sucked – and received a terrifying glare for his trouble from Big Chick, Prince’s ever-present bodyguard. But Magnoli was convinced his concept was better: a blend of music, romance, street-speak, Prince’s vulnerability and his ultimate vindication, while keeping some of the darker tones (e.g. the violent father) Prince insisted on. Magnoli talked for 10 minutes, animatedly describing scenes and characters. Sending Big Chick home, Prince took Magnoli for a drive.

“He pulled off the freeway and we ended up on a pitch-black road,” Magnoli says, “with complete darkness either side. I later learned that this was a short cut to his house, through a cornfield. We were quiet for a while, and he turned to me and said, ‘Listen, do you know me? Do you know anything about me?’ I said, ‘No, all I’ve heard is “1999”.’ He said, ‘Well, how come you just told me my life story in 10 minutes?’ I said to him, ‘Look, if you’re committed to getting punched in the face on page five, we can make a movie together.’ He laughed and said, ‘I’m willing to do that.’”