Hedonism on such an industrial scale could not last and soon enough extracted its inevitable price. By 1987, Mercury was too ill to tour and when he died of complications from AIDS in November 1991, it seemed that Queen had expired with him. Four years later came Made In Heaven, a posthumous album containing the material Mercury was working on with Brian May, Roger Taylor and John Deacon at the time of his death. And yet, a decade and a half after the singer’s death, the mighty Queen are back, fronted by former Free/Bad Company singer Paul Rodgers, who was once alarmingly nominated by Tony Blair as his favourite rock vocalist.

Now, Queen were never cool. They were way too over-the-top for that. But their reformation comes at a time when their critical stock has never been higher, with bands such as The Darkness and Scissor Sisters owing them a debt and everyone from The Foo Fighters to The Killers singing their praises. Demand for tickets for their first tour in almost 20 years is bound to be enormous, but the recruitment of Rodgers is also certain to prove controversial. The recent reformation of The Doors under similar circumstances, with The Cult’s Ian Astbury filling the shoes of Jim Morrison, has divided fans down the middle.

But then, Queen never cared much for reputation. From their formation in 1970, Queen pushed the boundaries musically, visually and commercially. According to Roger Taylor: “It was Freddie who instilled in us the belief that we had to make people gasp every time.” Yet the gasps were initially muted, and Queen struggled to make an impact on an early-’70s British rock scene dominated on the one hand by Bowie’s androgynous alien and Bolan’s bopping, pouting, glitter pixie and, on the other, by the cosmic pretensions of Yes, ELP and the prog-rock contingent. Somewhere in between was the art-rock of Roxy Music and the witty pop pastiches of 10cc and Sparks, who Queen found themselves supporting at an early gig at the Marquee.

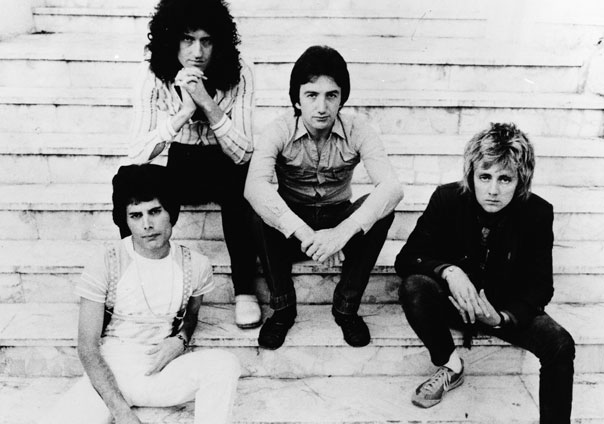

It was hard to see quite where Queen’s bombastic combination of camp theatricality and heavy rock fitted. Even by the standards of the times, they were outsiders. Brian May, the poodle-permed astronomer who’d joined the band during a PhD on Motions Of Interplanetary Dust, fashioned guitars out of old fireplaces and quaintly employed a sixpenny coin as a plectrum. Dentist-turned-drummer Roger Taylor had the look of a dissolute 1930s Hollywood lothario. Science student John Deacon on bass was anonymous to the point of invisibility.

Then there was Freddie Mercury. Born Farrokh Bulsara in 1946 to Persian parents in Zanzibar, Mercury had arrived in the suburbs of Bohemian London in 1963 with the vague notion of pursuing a career in graphic design or fashion. Having enrolled at Ealing College (previous alumni: Pete Townshend and Ron Wood), he drifted into music, fronting a series of uncelebrated bands including Wreckage and Ibex.

He also developed a flair for sartorial bravura. Friends of the time recall him walking along London’s Portobello Road dressed as a pirate, or decked out in leather and feather boas. His flamboyance was matched by an ambition that one associate described as “full of volcanic, pent-up urgency”. Long before Queen fell into place, Mercury’s self-belief bordered on the fanatical.

“I’m not going to be a star,” he’d announce to anyone who’d care to listen. “I’m going to be a legend.”