You are, I guess, never finished with Neil Young. A few weeks ago, as we were wrapping up an Uncut Ultimate Music Guide special dedicated to him, the news came through that Young was moving on again. Just as we thought we’d put together a comprehensive survey of all his recorded work, another Archives Performance Series release crept onto the schedules. Not to be a ungrateful grouch about this, but “Volume 02.5: Live At The Cellar Door” didn’t immediately look the most tantalising episode of Young’s ongoing retrospective project. Was it another of his digressive ruses to prolong the wait for Volume 2 of the Archives series proper (the one including, the more optimistic among us believe, all those unreleased albums from the mid-‘70s)? Why another solo set from the “After The Goldrush”/“Harvest” period – one recorded in Washington DC, in fact, only a month or two before the “Live At Massey Hall” set – instead of, say, the “Toast” Crazy Horse album that fell on and off the schedules a few years back? Young’s thinking behind digging out “Live At The Cellar Door” is as oblique as ever (we’ll get round to some speculation later). But it transpires that the 13-track set, pasted together from six shows on the cusp of November and December 1970, is a valuable addition to the Young motherlode. Solo versions of “Down By The River”, “Don’t Let It Bring You Down”, “Bad Fog Of Loneliness” and so on are as good as you might expect, but the real gold here comes in the fact that six of the 13 tracks are solo piano pieces: “After The Gold Rush”, “Expecting To Fly”, “Birds”, “See The Sky About To Rain”, “Cinnamon Girl” and “Flying On The Ground Is Wrong”. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=82gvrh6GXuE “I’ve been playing piano seriously for about a year,” he says before “Flying On The Ground Is Wrong”, “and I had it put in my contract that I would only play on a nine foot Steinway grand piano, just for a little eccentricity.” As he’s talking, Young is messing about with the piano strings, an apparently aimless fidgeting that, as he starts talking about getting high, reveals itself to be a kind of theatrically disorienting scene-setting. Abruptly, the discordance stops and a beautiful version of “Flying On The Ground Is Wrong” emerges, with all its elegiac power intact. One of the great pleasures of “Live At The Cellar Door” is the way it illustrates how malleable Young’s songs can be. “Cinnamon Girl”, for instance, is hardly diminished by that lunging riff being replaced by a quasi-baroque flurry of notes. Listen out, especially, for a powerful moment when Young sings “Loves to dance/Loves to…” and allows himself to be overwhelmed as his playing suddenly shifts from tenderness to a new bluesy intensity. “That’s the first time I ever did that one on the piano,” he notes at the death, and I’m not sure he’s done it again many times since. Best of all is the version of “Expecting To Fly”. The take on “Sugar Mountain - Live at Canterbury House 1968” shows how Young’s ornate studio confection could be potently reconfigured in a solo context. This piano study, though, is even better; crashing, plangent notes juxtaposed, with disingenuous artlessness, up against the fragility of his voice. Here, too, there’s an intimation of what is to come next, in 1971, as “Expecting To Fly”’s evolves to contain hints of “A Man Needs A Maid”. As is the case so often, it shows Young working over his past to find a lead to pursue into the future. So, is that how we should understand the arrival of “Live At The Cellar Door” at this point in Young’s career? Will the Carnegie Hall shows in January, presumably solo, put the spotlight on the piano over the guitar? Can Young’s latest strategy to stretch himself be a solo piano album, as Crazy Horse are parked once more and his other band options appear limited following the death of Ben Keith? Or is this yet another bizarre, compelling false lead in a career that’s been full of such capricious swerves and dummies from its very beginning? This, latter, picture is one that comes through strikingly in the aforementioned Neil Young Ultimate Music Guide, which goes on sale towards the end of this week. At 68, Young remains more restless, unpredictable and hyper-productive than any other artist of a comparable age and reputation. Since 2000, The Rolling Stones have released one new album, while Bob Dylan and Paul McCartney have managed five each. Bruce Springsteen has produced six; Tom Waits, four; Leonard Cohen and David Bowie three apiece. In that time, Young has come up with an autobiography, seven personally-curated archive releases, five films, an environmentally-friendly car and a new audio format, plus the small matter of ten new albums. It is an eccentric, if not always magnanimously received, body of work that tells the tale of an artist driven to spontaneous creation, whim, rough-hewn experiments and rapid emotional responses that pay little heed to the expectations of his paymasters and, sometimes, his fans. These are themes that run through the 148 pages of our latest Ultimate Music Guide: through interviews from the NME, Melody Maker and Uncut archives which reveal that, among many things, Young has been consistent in his contrary single-mindedness. The new reviews of every one of his albums provide a similarly weird and gripping narrative, finding significant echoes and hidden treasures on even his most misunderstood and neglected ‘80s records. “You can’t worry about what people think. I never do. I never did, really,” Young told Uncut in 2012. Our Ultimate Music Guide is proof: one of rock’s greatest runs, anatomised and celebrated in all its weird, ragged glory… Follow me on Twitter: www.twitter.com/JohnRMulvey This edition of the Ultimate Music Guide is in shops now, but you can also order it online here. The digital edition available to download on digital newsstands including Apple, Zinio and Google Play from Friday, November 29.

You are, I guess, never finished with Neil Young. A few weeks ago, as we were wrapping up an Uncut Ultimate Music Guide special dedicated to him, the news came through that Young was moving on again. Just as we thought we’d put together a comprehensive survey of all his recorded work, another Archives Performance Series release crept onto the schedules.

Not to be a ungrateful grouch about this, but “Volume 02.5: Live At The Cellar Door” didn’t immediately look the most tantalising episode of Young’s ongoing retrospective project. Was it another of his digressive ruses to prolong the wait for Volume 2 of the Archives series proper (the one including, the more optimistic among us believe, all those unreleased albums from the mid-‘70s)? Why another solo set from the “After The Goldrush”/“Harvest” period – one recorded in Washington DC, in fact, only a month or two before the “Live At Massey Hall” set – instead of, say, the “Toast” Crazy Horse album that fell on and off the schedules a few years back?

Young’s thinking behind digging out “Live At The Cellar Door” is as oblique as ever (we’ll get round to some speculation later). But it transpires that the 13-track set, pasted together from six shows on the cusp of November and December 1970, is a valuable addition to the Young motherlode. Solo versions of “Down By The River”, “Don’t Let It Bring You Down”, “Bad Fog Of Loneliness” and so on are as good as you might expect, but the real gold here comes in the fact that six of the 13 tracks are solo piano pieces: “After The Gold Rush”, “Expecting To Fly”, “Birds”, “See The Sky About To Rain”, “Cinnamon Girl” and “Flying On The Ground Is Wrong”.

“I’ve been playing piano seriously for about a year,” he says before “Flying On The Ground Is Wrong”, “and I had it put in my contract that I would only play on a nine foot Steinway grand piano, just for a little eccentricity.” As he’s talking, Young is messing about with the piano strings, an apparently aimless fidgeting that, as he starts talking about getting high, reveals itself to be a kind of theatrically disorienting scene-setting.

Abruptly, the discordance stops and a beautiful version of “Flying On The Ground Is Wrong” emerges, with all its elegiac power intact. One of the great pleasures of “Live At The Cellar Door” is the way it illustrates how malleable Young’s songs can be. “Cinnamon Girl”, for instance, is hardly diminished by that lunging riff being replaced by a quasi-baroque flurry of notes. Listen out, especially, for a powerful moment when Young sings “Loves to dance/Loves to…” and allows himself to be overwhelmed as his playing suddenly shifts from tenderness to a new bluesy intensity. “That’s the first time I ever did that one on the piano,” he notes at the death, and I’m not sure he’s done it again many times since.

Best of all is the version of “Expecting To Fly”. The take on “Sugar Mountain – Live at Canterbury House 1968” shows how Young’s ornate studio confection could be potently reconfigured in a solo context. This piano study, though, is even better; crashing, plangent notes juxtaposed, with disingenuous artlessness, up against the fragility of his voice. Here, too, there’s an intimation of what is to come next, in 1971, as “Expecting To Fly”’s evolves to contain hints of “A Man Needs A Maid”. As is the case so often, it shows Young working over his past to find a lead to pursue into the future.

So, is that how we should understand the arrival of “Live At The Cellar Door” at this point in Young’s career? Will the Carnegie Hall shows in January, presumably solo, put the spotlight on the piano over the guitar? Can Young’s latest strategy to stretch himself be a solo piano album, as Crazy Horse are parked once more and his other band options appear limited following the death of Ben Keith? Or is this yet another bizarre, compelling false lead in a career that’s been full of such capricious swerves and dummies from its very beginning?

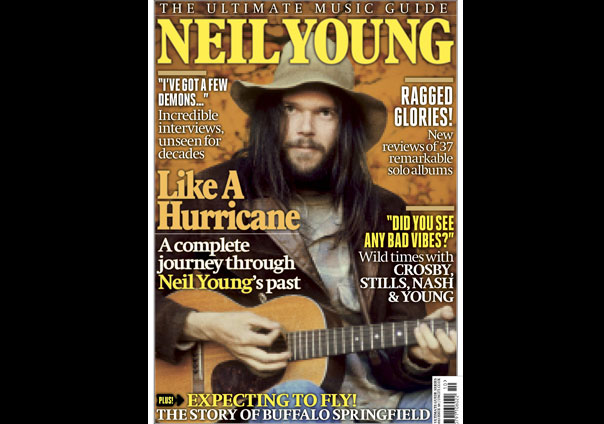

This, latter, picture is one that comes through strikingly in the aforementioned Neil Young Ultimate Music Guide, which goes on sale towards the end of this week. At 68, Young remains more restless, unpredictable and hyper-productive than any other artist of a comparable age and reputation. Since 2000, The Rolling Stones have released one new album, while Bob Dylan and Paul McCartney have managed five each. Bruce Springsteen has produced six; Tom Waits, four; Leonard Cohen and David Bowie three apiece. In that time, Young has come up with an autobiography, seven personally-curated archive releases, five films, an environmentally-friendly car and a new audio format, plus the small matter of ten new albums. It is an eccentric, if not always magnanimously received, body of work that tells the tale of an artist driven to spontaneous creation, whim, rough-hewn experiments and rapid emotional responses that pay little heed to the expectations of his paymasters and, sometimes, his fans.

These are themes that run through the 148 pages of our latest Ultimate Music Guide: through interviews from the NME, Melody Maker and Uncut archives which reveal that, among many things, Young has been consistent in his contrary single-mindedness. The new reviews of every one of his albums provide a similarly weird and gripping narrative, finding significant echoes and hidden treasures on even his most misunderstood and neglected ‘80s records.

“You can’t worry about what people think. I never do. I never did, really,” Young told Uncut in 2012. Our Ultimate Music Guide is proof: one of rock’s greatest runs, anatomised and celebrated in all its weird, ragged glory…

Follow me on Twitter: www.twitter.com/JohnRMulvey

This edition of the Ultimate Music Guide is in shops now, but you can also order it online here.

The digital edition available to download on digital newsstands including Apple, Zinio and Google Play from Friday, November 29.