There's a revealing scene in 20,000 Days On Earth, the fictionalised account of a day in Nick Cave's life, where the singer meets his chief collaborator Warren Ellis for lunch. Over eels and pasta, the two musicians share a fruity anecdote about Nina Simone (punch line: “champagne, cocaine and sau...

There’s a revealing scene in 20,000 Days On Earth, the fictionalised account of a day in Nick Cave‘s life, where the singer meets his chief collaborator Warren Ellis for lunch. Over eels and pasta, the two musicians share a fruity anecdote about Nina Simone (punch line: “champagne, cocaine and sausages”) that underscores the idea of performance as a transformative experience; one of the many threads running through Iain Pollard and Jane Forsyth’s exceptional work.

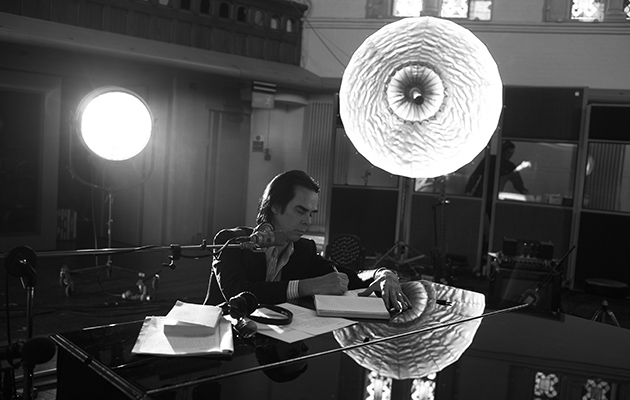

Andrew Dominik’s new film, One More Time With Feeling, finds Cave similarly interrogating the creative process – though it comes freighted with unimaginably heavy baggage: the death of Cave’s 15 year old son, Arthur, in July 2015, midway through recording the latest Bad Seeds studio album, Skeleton Tree. Cutting between Cave finishing recording the album at La Frette Studios, France during Autumn 2015, performing it at London’s Air studios with the Bad Seeds and a series of interviews with the filmmaker, One More Time With Feeling reveals a family coming to terms with their loss and a group of musicians who are trying to plot a course through a difficult emotional time with honesty and dignity. If 20,000 Days On Earth was an exercise in blurring truth and fiction, One More Time With Feeling finds Cave very much laid bare. “We all wish we had something to write about,” he tells Dominik. “But all that trauma and the way this happened, it was extremely damaging for the creative process.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=svru1jNLIK8

There is plenty of this kind of pontificating and self-scrutiny as Cave attempts to make sense of his tragedy within the context of his art. Is that even possible, he wonders? His earlier narrative songs, he explains, “held my life together at a point.” Now, he continues, “I don’t believe that life is like that. A pleasing resolve.” He expresses self-doubt – “You decay and you diminish. The struggle to do what I do becomes harder” – and finds rueful black humour in the physical toll of his son’s death. “I look like a battered monument.” Elsewhere, he discusses the prophetic nature of songwriting, the elasticity of time and a fear of words; but often these ideas go nowhere or he later discounts them. You sense Cave is exploring the depth and breadth of his feelings as he goes along. He tells of crying in his friend’s arms in the street, only to realise it was a stranger, and the “kind looks” he gets in the queue at his local bakers. He asks rhetorically, “When did you become an object of pity?”

Cave is not alone in his struggle, of course. His wife, Susie Bick, becomes an increasingly significant presence as the film progresses. In one heart-breaking scene, she shows Dominik a picture Arthur painted, when he was five, of a local windmill; coincidentally, it is near the site where he died last year. Arthur’s surviving twin, Earl, also appears; a normal teenage boy, it seems. But there’s a moment when the camera catches him reflexively stroking the back of his mother’s hair – an intimate, protective gesture.

Cave and Dominik have form together. Cave wrote the score for and appeared in Dominik’s Western, The Assassination Of Jesse James By The Coward Robert Ford; Cave invited Dominik to film One More Time With Feeling. In a director’s statement, Dominik outlines Cave’s thoughts going into the film: “Nick told me that he had some things he needed to say, but he didn’t know who to say them to. The idea of a traditional interview, he said, was simply unfeasible but that he felt a need to let the people who cared about his music understand the basic state of things. It seemed to me that he was trapped somewhere and just needed to do something – anything – to at least give the impression of forward movement.”

The friendship between the two men allows for some levity to enter the proceedings. At the start, there is some relaxed back and forth about what shirt Cave should wear to the studio and Cave’s dryly disparaging views on Dominik’s “ridiculous 3D black and white camera”. Later, Cave and Ellis discuss the lustrous quality of Cave’s hair. “Is my hair all right?” “Never looked better. Proceed with confidence.” Ellis is a critical part of the film and the early part of the film follows him and Cave during the recording and editing process for Skeleton Tree, as they discuss comparatively mundane things like re-recording a vocal that didn’t quite work. Gradually, Ellis’ role changes becomes less clearly defined, but evidently his work behind the scenes – literally, metaphorically, spritually – is invaluable. “What would I do without him?” Cave muses. “He is holding everything together.”

There is, of course, music in Dominik’s film. While at Air Studios, Cave sits at his piano in the centre of the room with Ellis opposite him; the rest of the Bad Seeds stepping into view when their particular skills are required. It’s largely a two-man show – Cave at his piano, while Ellis provides support with violin and an array of sonic effects. The songs are pillowed by vaporous electronic backing – in the film, you frequently see Ellis rocking back and forth, hunched over his MicroKorg keyboard – that recall the slow-moving, aquatic drift of Push The Sky Away and the textural explorations of Cave and Ellis’ deceptively simple and stripped-down soundtracks. Here, Ellis’ violin and keyboard wreath the songs like mist, imbuing them with a soft, mournful ambience.

The tone is set by “Jesus Alone”, where Cave sing-speaks over a backing of spectral analogue washes and electronic whistling. “You fell from the sky / Crash-landed in a field near the River Adur” begins Cave and this seems as close as the album gets to specifically addressing his son’s death. Even at its most abstract – “a ghost song lodged in the throat of a mermaid” – the song is steeped in anguish and pain. “With my voice, I am calling you” Cave repeats in the chorus. “Girl In Amber” finds Cave, accompanied by a simple cycling piano refrain and a discreet string motif, continuing to explore his grief: “I used to think that when you died you kind of wandered the world in a slumber till you crumbled, were absorbed into the earth, but I don’t think that any more”. “Magneto”, meanwhile, is framed only by a few piano notes, a strange hiss like a detuned radio set and the occasional strum of an acoustic guitar. A depiction of the effects of trauma, “In the bathroom mirror, I see me vomit in the sink”, it contains one of the album’s best lines – simultaneously funny and dark – “I had such hard blues down there in the supermarket queues”. All the same, the atmosphere is so spare and intimate, you feel like you’re curled up deep inside Cave’s piano.

“Anthrocene” continues to address head-on concepts of loss (“All of the things we love, we love, we love, we lose”) while the song itself – loose-limbed, skittish – spins around him. In Dominik’s film, we see Thomas Wydler almost levitate off his stool as he moves fluidly round his drum kit delivering susurrating flourishes of percussion; Jim Sclavunos, meanwhile, adds subtle xylophone flourishes. At one point, Cave explains to Dominik that the naked nature of the songs are reflective of the emotions Cave and his band are attempting to process. It is evident on “I Need You”, which appears to be a direct appeal to Bick. Over a sighed chorus from the Bad Seeds, and swelling and subsiding MiniKorg lines, Cave sings, “Just breathe, just breathe, I need you”.

There is something unexpectedly yearning – and deeply moving – about “Distant Sky”, as Ellis’ violin swells and rises to meet Else Torp’s uplifting soprano contribution. “Let us go now my only companion, set out for the distant sky, soon the children will be rising, will be rising, this is not for our eyes”. The album closes with the title song, buoyed along on a gently lilting piano melody and slow acoustic strum, it has the same sense of space as “Brompton Oratory” – arguably, The Boatman’s Call is possibly the most appropriate point of comparison for Skeleton Tree. Another deeply personal album, with the singer addressing love and pain in a similarly open-hearted fashion and in which the Bad Seeds were required to rethink their requirements. “Skeleton Tree”, at last, finds a sliver of hope at the album’s end: “And it’s alright now”, he sighs, although to whom this reassuring sentiment is directed isn’t clear.

Follow me on Twitter @MichaelBonner

Uncut: the spiritual home of great rock music.