A bit hard to concentrate on other music this morning, as the phoney war leading up to whenever Radiohead decide to release something continues apace. It occurred to me, though, that I should probably post a few reviews of recent favourites here, prompted in part by the fact that The Dead Tongues st...

A bit hard to concentrate on other music this morning, as the phoney war leading up to whenever Radiohead decide to release something continues apace. It occurred to me, though, that I should probably post a few reviews of recent favourites here, prompted in part by the fact that The Dead Tongues start their UK tour with Phil Cook in London tonight.

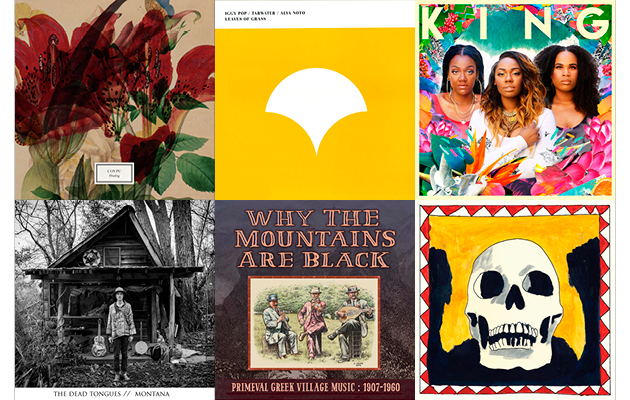

For a few of us, the fertile North Carolina scene centred on Hiss Golden Messenger’s MC Taylor and Cook has been a revelation this decade, and Asheville’s Ryan Gustafson is very much a part of that expanding fraternal network. Gustafson currently plays guitar in Cook’s soulful live band, but his second album as The Dead Tongues mostly takes a folksier path, with hearty fiddle tunes, and plenty of elevated fingerpicking on banjo and acoustic. “Montana” is more than a showcase for a virtuoso musician, though. It reveals Gustafson as a fine artisanal singer-songwriter, often Dylanish in tone, and with at least one song – the twanging, swaggering, Mellotron-dusted “Graveyard Fields” – strong enough to have sat on HGM’s classic, Lateness Of Dancers.

https://soundcloud.com/winsome-management/graveyard-fields-by-the-dead-tongues

The very fine Kevin Morby is also in town this week, and while he makes rapid strides in his solo career, the progress of his former band, Woods, is gentler, more incremental. “City Sun Eater In The River Of Light” is the ninth album by Jeremy Earl’s shifting cabal, and one which compounds the advances of “Bend Beyond” (2012) and “With Light And With Love” (2014). Where once there was lo-fi whimsy, a certain crispness is now prevalent, along with expanded horizons and budgets that can accommodate the occasional horn section, or the tentative funk of “Can’t See At All”. Earl’s songcraft, meanwhile, continues to be refined: if only his voice were as strong as the guitar soloing which so gleefully knocks the likes of “Sun City Creeps” and “I See In The Dark” off their axes.

In all the clamour surrounding his hook-up with Josh Homme (Post Pop Depression), a second new Iggy Pop project has rather slipped under the radar. “Leaves Of Grass”, on Morr Music, finds him reading a clutch of Walt Whitman poems, while a coalition of German electronicists formed from Tarwater and Alva Noto provide discreetly glitchy soundscapes. Thanks in no small part to Iggy’s voice, a tool now of great visceral gravitas, it works brilliantly. In his notes, he compares Whitman to Elvis, and suggests the poet would’ve made “the perfect gangster rapper”. Pop himself, though, is a better embodiment of Whitman’s muscular sensualism: “Lusty, phallic, with the potent original loins… bathing my songs in sex”; “Singing the phallus, singing the song of procreation.”

A couple from the boutique UK label, MIE Music. Ben Chasny’s work as Six Organs Of Admittance has recently taken a forbidding theoretical turn, based on his new “Hexadic” compositional system. As yet, however, the radical practice doesn’t seem to have infected his collaborations; either in the mighty, jamming Rangda, or on this somewhat shadowy project. Coypu finds Chasny in the company of a mostly Italian crowd, with deep underground CVs (Larsen? Blind Cave Salamander?), and a faintly gothic arsenal of effects to back up Chasny’s ever-thoughtful guitar lines. At times, the monkish clank and drone of “Floating” recalls outliers like Nurse With Wound. Highlights, though, are transcendent more than transgressive, notably “March Of The River Rats”, a rippling invocation of Popol Vuh – and, indeed, the more accessible Six Organs of old.

Much like the Coypu album, Portland’s Dreamboat serenely pits a folkish singer/guitarist – in this case Ilyas Ahmed – against kosmische-inclined new collaborators; here, the Thrill Jockey duo, Golden Retriever. Ahmed cuts an appealingly desolate figure on “Dreamboat”‘s two long pieces, given plenty of space in Matt Carlson and Jonathan Sielaff’s humid synthscapes. The tools are slightly different, not least Sielaff’s processed clarinet looming out of the murk at intervals, but the prevailing atmosphere often resembles that found on late ‘90s records by Flying Saucer Attack: a gentle music in which melancholy is given apparently boundless time and space to try and work itself out.

Not be confused with the “Love And Pride” hitmakers, LA trio King instead conjure up a seductive alternative ‘80s on debut “We Are King”, as if an R&B production machine like Jam & Lewis had become infatuated with the downy textures of the Cocteau Twins. The aquarian soul of Erykah Badu is another antecedent for this meticulous debut, written, produced and performed by Paris Strother, along with twin sister Amber and Anita Bias. “We Are King” is too laidback and classy to be anywhere near as triumphalist as its name implies, and the 12 lovely songs have such a languid unity of purpose, it can be hard to tell where one stops and the next starts. Still, try “Red Eye”, with its melodic richness redolent of peak ‘70s Stevie Wonder.

Finally, a remarkable comp on Third Man: “Why The Mountains Are Black: Primeval Greek Village Music 1907-1960”. “No ancient Western culture valued music more highly than the ancient Greeks,” writes Christopher King in the sleevenotes to this 2CD set of revelations, taking a longer view of cultural history than most CD compilers. The music harvested by King from precious 78s provides a connection between this formative civilization and 20th Century America, as the Greek diaspora bring their traditions to the States. The duelling bagpipe music played here by Zembellas and Mailles on two tracks, for instance, originates on two small islands in the Aegean. By the time of the recordings in 1950, however, this Tsabouna music had migrated to Tarpon Springs, Florida, where many of its practitioners had relocated to ply their trades as free-diving sponge fishermen. King, also a noted collector of old blues records, makes big claims for the social necessity of this music: “It was an essential tool for survival,” he claims, “as natural and as necessary as any object crafted for hunting.” Critically, though, it’s also wildly entertaining in a way which transcends historical context: check “Enas Aetos-Tsamiko”, a nimble and uproarious 1926 jam, recorded in 1926, that King identifies as kin to the hot jazz of the time.