As Robert Gordon reminds us in Respect Yourself: Stax Records And The Soul Explosion, his terrific account of the rise and fall of the great Memphis soul imprint, the Stax story is more than a record-label history. “It is an American story,” Gordon writes,” where the shoe-shine boy becomes a star, the country hayseed an international magnate. It’s the story of individuals against society, of small business competing with large, of the disenfranchised seeking their own tile in the American mosaic.” The success of Stax in its heyday was astonishing. Between 1960 and 1975, it released 800 singles and 300 albums, a huge proportion of them major hits on both the R&B and pop charts, the label making international stars of Otis Redding, Isaac Hayes, Sam and Dave, Booker T & The MG’s, Wilson Pickett and The Staple Singers, the label growing from homespun beginnings to a major money-making conglomerate with breath taking velocity. For Gordon, who grew up in Memphis as Stax was establishing its commercial supremacy, it remains nothing less than miraculous that a label that recognised no racial boundaries, whose founders were white but whose talent pool was largely drawn from the local black communities, should have flourished in a place where deep into the 20th century “plantation prejudices still prevailed”. As was the case with so many cities in America’s Deep South, racism in Memphis was deeply institutionalised. US President Lyndon Johnson may have introduced the Civil Rights Act in 1964, but Memphis simply ignored it, as if federal legislation had no legitimacy here and would therefore not be heeded or obeyed. The black population of Memphis thus remained unrecognised and unrepresented in local government, and was allowed no municipal voice. Its grievances and claims for equality were routinely brushed aside, an unwelcome chorus of complaint. In the converted cinema at 926 East McLemore Avenue in South Memphis where Stax built the legendary studio where in time it cranked out hit after hit after hit, young black and white musicians worked together freely. But outside, they were separated by the imperatives of strict and unforgiving segregation. In the circumstances, Stax, in Gordon’s words, became “an accidental refuge that flourished… nourished by a sense of decency” whose music “became the soundtrack for liberation, the song of triumph, the sound of the path toward freedom”. Such aspirations were not paramount in Jim Stewart’s ambitions when he modestly started Satellite Records in 1957. Stewart was 27 years old, working in a bank, studying law at night on the GI Bill and playing fiddle in a country band at weekends. Encouraged by the recent local example of Sam Phillips, a former mortuary assistant and radio technician who had made such a spectacular success of Sun Records, Stewart launched his own label as a side line that quickly became an obsession, an opportunity to make a few quick bucks that within a few years became the all-conquering Stax juggernaut. With crucial investment from his sister, Estelle Axton, Stewart moved Satellite from the rural garage where he recorded the label’s first records to the site of the old Capitol movie theatre on McLemore Avenue, changing the label’s name to Stax (a conflation of Jim and Estelle’s surnames, STewart/AXton) in the process. Gordon warmly relates the label’s initial rise, as Stewart and Axton, with vital initial input from engineer Chips Moman (subsequently ousted in an early power struggle), attracted and encouraged what turned out to be a torrent of interracial local talent, a seemingly inexhaustible tide of gifted songwriters, arrangers and musicians, including The MG’s, who became the Stax house band, most of whom were still in high school when the label started. Drawing on a vast archive of vivid interviews originally conducted for a PBS documentary on Stax, Gordon allows us to relive these exciting times. The fledgling label’s early success brought it to the attention of Jerry Wexler at Atlantic, whose distribution network brought Stax product to a national audience as part of a production deal that would eventually cost the Memphis label dearly. When the hits started coming, there seemed to be no end to them. The company grew quickly, many of its major artists discovered by its open door policy, aspiring talent often just walking in off the street, into the studio and onto the charts. These were heady times, with hits for Sam and Dave, Booker T & The MGs, William Bell, Rufus and Carla Thomas, Eddie Floyd, Wilson Pickett and, of course, Otis Redding, who after his incendiary performance at the Monterey festival introduced him to a huge new white audience was on his way to becoming an international superstar when he was killed in a plane crash that also claimed the lives of most of his backing band, The Bar-Kays. Many would later claim that Stax never recovered from the loss of Otis and it was further deeply demoralised when Warner Bros bought out Atlantic who it now turned out owned their entire back catalogue, the result of an overlooked clause in their original agreement of which Wexler later unconvincingly argued he had no knowledge. Martin Luther King’s assassination in Memphis early the following year further soured the atmosphere between black and white employees at Stax who previously had given no thought to race. Former Memphis DJ Al Bell had been brought to Stax by Jim Stewart in 1965 as national promotions director now became increasingly influential, introducing a bold new programme of expansion that included the almost-instant creation of a whole new catalogue, funded by heavy duty loans that put the company hugely in debt but made a superstar of Isaac Hayes, who briefly brought Stax even greater riches, even as the label’s original creative core began to splinter, in often bitter circumstances as Bell brought in his own people, including the gun-toting enforcer Johnny Baylor, whose criminality presaged the widespread corruption revealed in the company’s subsequent fall from grace amid a tsunami of litigation and unpaid debts, the label’s decline as spectacular in every instance as its brief but incredible ascendency.

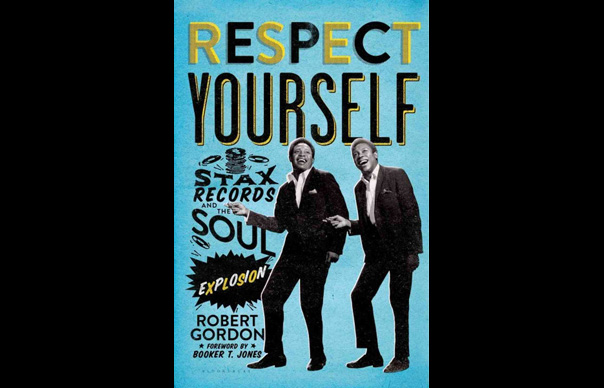

As Robert Gordon reminds us in Respect Yourself: Stax Records And The Soul Explosion, his terrific account of the rise and fall of the great Memphis soul imprint, the Stax story is more than a record-label history. “It is an American story,” Gordon writes,” where the shoe-shine boy becomes a star, the country hayseed an international magnate. It’s the story of individuals against society, of small business competing with large, of the disenfranchised seeking their own tile in the American mosaic.”

The success of Stax in its heyday was astonishing. Between 1960 and 1975, it released 800 singles and 300 albums, a huge proportion of them major hits on both the R&B and pop charts, the label making international stars of Otis Redding, Isaac Hayes, Sam and Dave, Booker T & The MG’s, Wilson Pickett and The Staple Singers, the label growing from homespun beginnings to a major money-making conglomerate with breath taking velocity. For Gordon, who grew up in Memphis as Stax was establishing its commercial supremacy, it remains nothing less than miraculous that a label that recognised no racial boundaries, whose founders were white but whose talent pool was largely drawn from the local black communities, should have flourished in a place where deep into the 20th century “plantation prejudices still prevailed”.

As was the case with so many cities in America’s Deep South, racism in Memphis was deeply institutionalised. US President Lyndon Johnson may have introduced the Civil Rights Act in 1964, but Memphis simply ignored it, as if federal legislation had no legitimacy here and would therefore not be heeded or obeyed. The black population of Memphis thus remained unrecognised and unrepresented in local government, and was allowed no municipal voice. Its grievances and claims for equality were routinely brushed aside, an unwelcome chorus of complaint. In the converted cinema at 926 East McLemore Avenue in South Memphis where Stax built the legendary studio where in time it cranked out hit after hit after hit, young black and white musicians worked together freely. But outside, they were separated by the imperatives of strict and unforgiving segregation. In the circumstances, Stax, in Gordon’s words, became “an accidental refuge that flourished… nourished by a sense of decency” whose music “became the soundtrack for liberation, the song of triumph, the sound of the path toward freedom”.

Such aspirations were not paramount in Jim Stewart’s ambitions when he modestly started Satellite Records in 1957. Stewart was 27 years old, working in a bank, studying law at night on the GI Bill and playing fiddle in a country band at weekends. Encouraged by the recent local example of Sam Phillips, a former mortuary assistant and radio technician who had made such a spectacular success of Sun Records, Stewart launched his own label as a side line that quickly became an obsession, an opportunity to make a few quick bucks that within a few years became the all-conquering Stax juggernaut. With crucial investment from his sister, Estelle Axton, Stewart moved Satellite from the rural garage where he recorded the label’s first records to the site of the old Capitol movie theatre on McLemore Avenue, changing the label’s name to Stax (a conflation of Jim and Estelle’s surnames, STewart/AXton) in the process.

Gordon warmly relates the label’s initial rise, as Stewart and Axton, with vital initial input from engineer Chips Moman (subsequently ousted in an early power struggle), attracted and encouraged what turned out to be a torrent of interracial local talent, a seemingly inexhaustible tide of gifted songwriters, arrangers and musicians, including The MG’s, who became the Stax house band, most of whom were still in high school when the label started. Drawing on a vast archive of vivid interviews originally conducted for a PBS documentary on Stax, Gordon allows us to relive these exciting times. The fledgling label’s early success brought it to the attention of Jerry Wexler at Atlantic, whose distribution network brought Stax product to a national audience as part of a production deal that would eventually cost the Memphis label dearly.

When the hits started coming, there seemed to be no end to them. The company grew quickly, many of its major artists discovered by its open door policy, aspiring talent often just walking in off the street, into the studio and onto the charts. These were heady times, with hits for Sam and Dave, Booker T & The MGs, William Bell, Rufus and Carla Thomas, Eddie Floyd, Wilson Pickett and, of course, Otis Redding, who after his incendiary performance at the Monterey festival introduced him to a huge new white audience was on his way to becoming an international superstar when he was killed in a plane crash that also claimed the lives of most of his backing band, The Bar-Kays. Many would later claim that Stax never recovered from the loss of Otis and it was further deeply demoralised when Warner Bros bought out Atlantic who it now turned out owned their entire back catalogue, the result of an overlooked clause in their original agreement of which Wexler later unconvincingly argued he had no knowledge. Martin Luther King’s assassination in Memphis early the following year further soured the atmosphere between black and white employees at Stax who previously had given no thought to race.

Former Memphis DJ Al Bell had been brought to Stax by Jim Stewart in 1965 as national promotions director now became increasingly influential, introducing a bold new programme of expansion that included the almost-instant creation of a whole new catalogue, funded by heavy duty loans that put the company hugely in debt but made a superstar of Isaac Hayes, who briefly brought Stax even greater riches, even as the label’s original creative core began to splinter, in often bitter circumstances as Bell brought in his own people, including the gun-toting enforcer Johnny Baylor, whose criminality presaged the widespread corruption revealed in the company’s subsequent fall from grace amid a tsunami of litigation and unpaid debts, the label’s decline as spectacular in every instance as its brief but incredible ascendency.