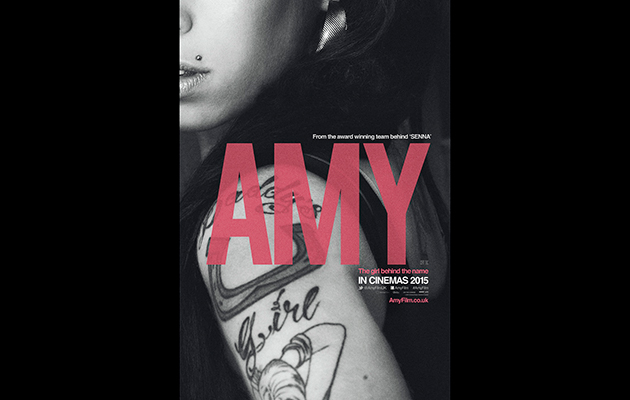

For an artist whose talents were in constant demand, Amy Winehouse meant different things to many people around her. To one, she was “the truest jazz singer I have ever heard”; another saw her as “an old soul in a young body”, while a third describes her as “a humble person caught up in a bad situation”. These various perspectives are all broadly accurate; but if there is one lesson we can take away from Asif Kapadia’s documentary it is that if Amy Winehouse chose her female friends well, the same is not necessarily true of the men in her life. Watching Kapadia’s film – from her childhood in Southgate, north London through her remarkable success up to her death in 2011 aged 27 – it is possible to see how badly she was let down by the male figures closest to her: an absentee father, an exploitative husband, a manager who appears out of his depth. “You like a powerful man,” observes an ex-boyfriend: it transpires that the exact opposite would be more appropriate.

Assembled from home video and mobile phone footage, as well as contemporaneous interviews, Amy opens in 1988 in Southgate, in suburban north London. A 14th birthday party is in progress, which catches Winehouse mucking around with her friends, Juliette Ashby and Lauren Gilbert. To illustrate Winehouse’s remarkable gifts, she delivers a breathy version of “Happy Birthday”. Ashby and Gilbert – along with her first manager, Nick Shymansky – are essentially the heart of Kapadia’s film. It is they who care the most, want only to help, when around Winehouse swarm a growing number of people who have their own strategies. The early footage of Winehouse, Shymansky and her guitarist Ian Barter as they play pool or smoke weed in the downtime between touring engagements is among the warmest in the film. Her performances during this period are far more expressive and wide-ranging than her later material.

As the film progresses, we learn how her father, Mitch Winehouse, began an affair when his daughter was 18 months old. “She got over it pretty quick,” he says; an early indication that he is not the most intuitive witness. By the time she reaches her teens, she is on anti-depressants. Regrettably, Winehouse is serially drawn to men of a similar disposition to Mitch: chief among them, Blake Fielder-Civil. While Kapadia is keen not to point any fingers, neither father nor ex-husband emerge well from this film. It is her father who later advises her not to attend a drying-out facility and who then arrives during what is ostensibly a fragile period of recovery for the singer on St Lucia with a full documentary crew in tow. If one is looking for a moment that best sums up Fielder-Civil’s part in Winehouse’s story, it may well be the scene filmed in a bar on their wedding day, where he asks the camera, “Who’s paying for this? I’m broke. Amy? Get us a bottle of Dom Perignon.” Fresh from their honeymoon, he introduces his new bride to heroin and crack cocaine. Her promoter-turned-manager, Raye Cosbert, meanwhile, seems to think nothing of sending her on a European tour days before she died.

Much as with Kapadia’s previous film, Senna – and also the recently released Kurt Cobain documentary – Amy relies on diligently researched archive footage. But it is the involvement of Ashby, Gilbert and Shymansky who are perhaps the film’s strongest asset: with no particular agenda, theirs feels the most unfiltered version of events. At one point, Ashby confesses that she stole Winehouse’s passport in order to prevent her from going on tour overseas: she was subsequently reprimanded for her troubles. Such revelations only further enhance the suspicion that the professionals who were responsible for Amy Winehouse’s well-being singularly failed in their endeavours. But that’s not to suggest Kapadia’s film presents Winehouse as a victim: she was far too complex and mercurial a personality for that.

Follow me on Twitter @MichaelBonner

AMY OPENS IN THE UK ON JULY 3