“I don’t have any plans to stop“, said Altman upon receiving his lifetime achievement Oscar earlier this year, “but history tells us I will”. Probably the most distinctive maverick of his generation, the Kansas-born director died on Monday in LA, aged 81. He’d made more films than he’d lived years. Among these were the great, the good and the woeful. His best work was satirical and atmospheric; his trademark interweaving narratives and multi-layered dialogues broke the mould and are often imitated. Is there a more common, lazily-applied adjective in film criticism than “Altmanesque”? He was already in his late 40s when 1970 anti-war black comedy MASH - already turned down by 17 other directors as potentially incendiary - made his name. “Oh, sure it’s a good film”, he told Uncut in 2001, “but that television series it became was despicable propaganda.” Studio suits watching rough cuts grumbled, “That idiot’s got them all talking at the same time”. On the back of its huge success (he never matched it commercially), he was allowed to develop his own style. In and out of fashion for the next three decades (in the Eighties he struggled to find funds), he was a constant force for subversion. “Trying to maintain the status quo is like trying to stop moving in a river”, he told us. “The film industry’s trivial and self-important. They just bow to the money. But there’s always dissent around the edges…” His sprawling ensemble casts - actors adored him, because he simply let them do what they were good at - graced such durable works as Nashville (75), A Wedding (78) and the Raymond Carver adaptation Short Cuts (93). He span genres on their heads: the Western in McCabe And Mrs Miller (71), noir in The Long Goodbye (73), British upstairs-downstairs class drama in Gosford Park (01). The Player (92) was an acid Hollywood lampoon which resurrected his career, though with typical perversity he told us, “That was just one film of many. It was superficial - the truth is much uglier. I preferred the one I made before that, Vincent And Theo…” His loose ends remained loose. “Life is not a puzzle to be solved”, he wrote, “but a riddle to be pondered.” Was that his abiding philosophy? “It’s true”, he said, ”there are no answers. You all seem to want happy endings. Well, I don’t know any happy endings. The only ending is death.” Yet on the way there his films shed fresh light on eternal truths, crackling with humour and poetry. “I’m a benevolent monarch on set”, he confided in us, eyes twinkling. “The others create, and I allow it. Most good things are an accident.” At the close of our 2001 interview, he said, “I’m always looking for another blank wall and some more paint. I just want to keep doing the same different things. I have a great life, lot of fun. I can’t envision myself not making films, I’ll probably die in the middle of one. But that’s all right. Although I’d rather die at the end of one.” A Prairie Home Companion will be released here next year. CHRIS ROBERTS

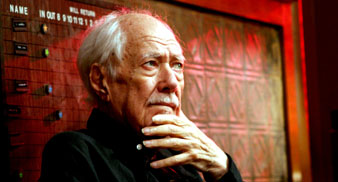

“I don’t have any plans to stop“, said Altman upon receiving his lifetime achievement Oscar earlier this year, “but history tells us I will”. Probably the most distinctive maverick of his generation, the Kansas-born director died on Monday in LA, aged 81. He’d made more films than he’d lived years.

Among these were the great, the good and the woeful. His best work was satirical and atmospheric; his trademark interweaving narratives and multi-layered dialogues broke the mould and are often imitated. Is there a more common, lazily-applied adjective in film criticism than “Altmanesque”?

He was already in his late 40s when 1970 anti-war black comedy MASH – already turned down by 17 other directors as potentially incendiary – made his name. “Oh, sure it’s a good film”, he told Uncut in 2001, “but that television series it became was despicable propaganda.” Studio suits watching rough cuts grumbled, “That idiot’s got them all talking at the same time”. On the back of its huge success (he never matched it commercially), he was allowed to develop his own style. In and out of fashion for the next three decades (in the Eighties he struggled to find funds), he was a constant force for subversion. “Trying to maintain the status quo is like trying to stop moving in a river”, he told us. “The film industry’s trivial and self-important. They just bow to the money. But there’s always dissent around the edges…”

His sprawling ensemble casts – actors adored him, because he simply let them do what they were good at – graced such durable works as Nashville (75), A Wedding (78) and the Raymond Carver adaptation Short Cuts (93). He span genres on their heads: the Western in McCabe And Mrs Miller (71), noir in The Long Goodbye (73), British upstairs-downstairs class drama in Gosford Park (01). The Player (92) was an acid Hollywood lampoon which resurrected his career, though with typical perversity he told us, “That was just one film of many. It was superficial – the truth is much uglier. I preferred the one I made before that, Vincent And Theo…”

His loose ends remained loose. “Life is not a puzzle to be solved”, he wrote, “but a riddle to be pondered.” Was that his abiding philosophy? “It’s true”, he said, ”there are no answers. You all seem to want happy endings. Well, I don’t know any happy endings. The only ending is death.”

Yet on the way there his films shed fresh light on eternal truths, crackling with humour and poetry. “I’m a benevolent monarch on set”, he confided in us, eyes twinkling. “The others create, and I allow it. Most good things are an accident.” At the close of our 2001 interview, he said, “I’m always looking for another blank wall and some more paint. I just want to keep doing the same different things. I have a great life, lot of fun. I can’t envision myself not making films, I’ll probably die in the middle of one. But that’s all right. Although I’d rather die at the end of one.” A Prairie Home Companion will be released here next year.

CHRIS ROBERTS