I don’t know if you saw it, but BBC2’s David Bowie documentary, Five Years, screened at the weekend, was very entertaining. A lot of the archive footage was familiar, but there were also some splendidly unexpected highlights, like a sequence of Bowie filmed at Andy Warhol’s Factory, which rather vividly suggested that Bowie’s talent for mime isn’t perhaps all it’s cracked up to be in which he pretended to unspool his own entrails and pluck out his heart, a performance that was doubtless accompanied by much sniggering from Andy's crowd. Elsewhere, there was plenty of exciting footage of Bowie as Ziggy and The Thin White Duke and you can never really get enough of so-called experts stating the fucking obvious in unusually loud voices. But by far the most eccentric contribution to the programme, however, came with the appearance of King Crimson’s Robert Fripp, who had some interesting things to say about playing guitar on ‘Heroes’ and pretty much stole the show in the process. “Anyone who’s playing ‘Beauty And The Beast’,” he said of that album’s opening track, a weird little glint in his eye. “You know they get erections.” I laughed out loud reading a review of Five Years in the following morning’s Observer, in which Fripp was described as looking like “Benny Hill would have looked if he’d hung out with Brian Eno and married Toyah Willcox”. This barely did justice to Fripp’s genuine oddness, of which I have some first-hand experience. In April 1979, I was despatched by Melody Maker to interview him about his new album, Exposure, his first solo album. I get the train down to Bournemouth and he drives over from the nearby village of Wimbourne, where he has a cottage, to meet me at the station. He starts talking before I have both feet on the platform and doesn’t stop for what seems like about four days of torrential chat that even as he negotiates the lunchtime traffic into the town centre in his neat green Volvo leaves me reeling and queasy and in danger of throwing up, which I later do. I am at the time of writing already sick – have in fact spent the last week coughing like a consumptive young Romantic poet, the doomed Chatterton, perhaps, pale unto death in a very big blouse and knickerbockers, fading away in a damp attic, adrift in bilious dreams. Fripp’s yapping is now making me feel wholly delirious. We go for a snack in some ghastly vegetarian place Fripp knows where over some kind of nut cutlet, we review his post-Crimson career – which notably takes in recordings with Peter Gabriel and with David Bowie and Eno on Heroes. He has also spent a lengthy spell at the International Academy For Continuous Education in Sherbourne, where he studied the teachings of mystic philosophers GI Gurdjieff and PD Ouspensky, the Sherbourne academy based on Gurdjieff’s own Institute For The Harmonious Development Of Man. Cutlets consumed and washed down with some sludgy vegetarian drink that looks like something a cat might have vomited up, we find ourselves in a local hostelry, packed with lunchtime drinkers. Fripp finds us a table which we share with two businessmen, who give us suspicious looks when I set up my tape recorder, which is when Fripp says he’d like – if I have no objection – to preface our interview with a statement he’s prepared, in which he will outline what he describes as a three year career plan called The Drive To 1981. I tell him to go ahead. “Thank you so much," he says, and begins to speak directly into my microphone as if he’s addressing a public meeting or a planning enquiry. Fully 40 minutes later, almost without taking a breath, he’s filled almost an entire side of C90 tape and is still going strong, eventually shedding light on what Exposure’s all about. “Exposure,” he says, “deals with tweaking the vocabulary of, for want of a better word, ‘rock’ music. It investigates the vocabulary and, hopefully, expands the possibilities of expression and introduces a more sophisticated emotional dynamic than one would normally find within ‘rock’.” Thus concludes Fripp’s opening statement, which he had begun nearly an hour ago. He looks at me. I’m speechless, quite overwhelmed. “ONE LANCASHIRE HOTPOT AND A CHEESE FLAN – THANKYEWWWW!” bellows the barmaid over the heads of the crowd. Fripp winces at the sound of her voice, but is quickly back in the conversational swing of things and soon telling me about his monastic tenure at the institute in Sherbourne, which sounds to me like a hell on earth. “There were 100 people living in the house,” he recalls breezily. “They’d come from all different walks of life, from different countries. In my year, we lost about 20 pupils, three of them to the asylum. It was very hard going, one of the most uncomfortable physical appearances of my life. It was always horribly cold. And it wasn’t just the physical cold. There was a kind of cold,” he says, voice lowering conspiratorially, the businessmen who have been listening to him with baffled fascination now leaning forward to catch what he says next, “that at times could chill the soul. . .” “ONE SAUSAGE EGG AND BEANS AND A CHEESE FLAN – THANKYEWWWW!” the barmaid screeches. “I shared a dormitory with five other men,” Fripp ploughs on. “One from Alaska, two Americans, an Irishman, a Polish American and an Italian. . .” (“Heard it,” I’m tempted to interrupt.) “The Italian,” Fripp goes on, “would wake up most mornings at 3 am and fart sufficiently loudly to wake me up. The Alaskan had his bed next to mine. He was always rather depressed and unhappy. His head was hunched into his shoulders, like this. . .” Fripp does an impression of a somewhat deformed Alaskan. The businessmen move nervously away from us. “One of my favourite memories of Sherbourne,” he’s telling me now, “is of being in a trench, digging for a water main. There I was at the bottom of an eight-foot trench, which has taken two days to dig, with 28 other people, all of whom without distinction I detest – suddenly it begins to rain. And then a cheerful voice at the top of this trench as one looks up says, ‘Hello! We’re digging in the wrong place! The water main’s over here! You’ll have to start again.’ “It was marvellous,” he says with a note of truly sombre reflection, “to have one’s lofty ideas of oneself so deflated. I mean, I think everyone who went into Sherbourne thought that God had selected them uniquely and specifically to save the universe, so it was a very, very useful deflation.” “LAST ORDERS, LADEEZNGENMEN, PERLEEESE,” the barmaid howls. “Time to move on,” Fripp announces, so we do – to somewhere called The Salad Centre, where we have some herbal tea that tastes like it’s been strained through someone’s dirty socks and Fripp talks and talks and talks and I begin to feel even more strangely disembodied and start wondering if I am going to be stuck forever in this strange purgatory where I will have to listen to Fripp’s apparently endless discourse as eternity unfolds, Fripp’s voice haunting me lo until the end of all time. I stare blankly at him, unable by now to take in whatever he’s saying – something about “riding the dynamics of disaster” – reduced to mystical static that means nothing to me. On and on he goes, until the light starts to drain from the day, even as all life begins to drain from me. We’re back at the station now, Fripp still talking. I want frankly to scream, beg him for a moment just to stop. But on he goes. I feel like setting fire to myself. Bile is rising in my throat. Where – oh, where – is my train? “I’m currently working on a completely new theory,” he says, and I’m afraid he’s going to tell me what it is, which he does. “I’m working on the theory that Christ spent the missing 12 years of his life in Wimbourne,” he begins, at which point I can stand it no more and promptly vomit where I stand. “Oh, dear,” says Fripp. “Might it have been the nut cutlets?” Pic: Michael Ochs Archives

I don’t know if you saw it, but BBC2’s David Bowie documentary, Five Years, screened at the weekend, was very entertaining. A lot of the archive footage was familiar, but there were also some splendidly unexpected highlights, like a sequence of Bowie filmed at Andy Warhol’s Factory, which rather vividly suggested that Bowie’s talent for mime isn’t perhaps all it’s cracked up to be in which he pretended to unspool his own entrails and pluck out his heart, a performance that was doubtless accompanied by much sniggering from Andy’s crowd.

Elsewhere, there was plenty of exciting footage of Bowie as Ziggy and The Thin White Duke and you can never really get enough of so-called experts stating the fucking obvious in unusually loud voices. But by far the most eccentric contribution to the programme, however, came with the appearance of King Crimson’s Robert Fripp, who had some interesting things to say about playing guitar on ‘Heroes’ and pretty much stole the show in the process.

“Anyone who’s playing ‘Beauty And The Beast’,” he said of that album’s opening track, a weird little glint in his eye. “You know they get erections.”

I laughed out loud reading a review of Five Years in the following morning’s Observer, in which Fripp was described as looking like “Benny Hill would have looked if he’d hung out with Brian Eno and married Toyah Willcox”. This barely did justice to Fripp’s genuine oddness, of which I have some first-hand experience.

In April 1979, I was despatched by Melody Maker to interview him about his new album, Exposure, his first solo album.

I get the train down to Bournemouth and he drives over from the nearby village of Wimbourne, where he has a cottage, to meet me at the station. He starts talking before I have both feet on the platform and doesn’t stop for what seems like about four days of torrential chat that even as he negotiates the lunchtime traffic into the town centre in his neat green Volvo leaves me reeling and queasy and in danger of throwing up, which I later do.

I am at the time of writing already sick – have in fact spent the last week coughing like a consumptive young Romantic poet, the doomed Chatterton, perhaps, pale unto death in a very big blouse and knickerbockers, fading away in a damp attic, adrift in bilious dreams. Fripp’s yapping is now making me feel wholly delirious.

We go for a snack in some ghastly vegetarian place Fripp knows where over some kind of nut cutlet, we review his post-Crimson career – which notably takes in recordings with Peter Gabriel and with David Bowie and Eno on Heroes. He has also spent a lengthy spell at the International Academy For Continuous Education in Sherbourne, where he studied the teachings of mystic philosophers GI Gurdjieff and PD Ouspensky, the Sherbourne academy based on Gurdjieff’s own Institute For The Harmonious Development Of Man.

Cutlets consumed and washed down with some sludgy vegetarian drink that looks like something a cat might have vomited up, we find ourselves in a local hostelry, packed with lunchtime drinkers. Fripp finds us a table which we share with two businessmen, who give us suspicious looks when I set up my tape recorder, which is when Fripp says he’d like – if I have no objection – to preface our interview with a statement he’s prepared, in which he will outline what he describes as a three year career plan called The Drive To 1981. I tell him to go ahead.

“Thank you so much,” he says, and begins to speak directly into my microphone as if he’s addressing a public meeting or a planning enquiry. Fully 40 minutes later, almost without taking a breath, he’s filled almost an entire side of C90 tape and is still going strong, eventually shedding light on what Exposure’s all about.

“Exposure,” he says, “deals with tweaking the vocabulary of, for want of a better word, ‘rock’ music. It investigates the vocabulary and, hopefully, expands the possibilities of expression and introduces a more sophisticated emotional dynamic than one would normally find within ‘rock’.”

Thus concludes Fripp’s opening statement, which he had begun nearly an hour ago. He looks at me. I’m speechless, quite overwhelmed.

“ONE LANCASHIRE HOTPOT AND A CHEESE FLAN – THANKYEWWWW!” bellows the barmaid over the heads of the crowd.

Fripp winces at the sound of her voice, but is quickly back in the conversational swing of things and soon telling me about his monastic tenure at the institute in Sherbourne, which sounds to me like a hell on earth.

“There were 100 people living in the house,” he recalls breezily. “They’d come from all different walks of life, from different countries. In my year, we lost about 20 pupils, three of them to the asylum. It was very hard going, one of the most uncomfortable physical appearances of my life. It was always horribly cold. And it wasn’t just the physical cold. There was a kind of cold,” he says, voice lowering conspiratorially, the businessmen who have been listening to him with baffled fascination now leaning forward to catch what he says next, “that at times could chill the soul. . .”

“ONE SAUSAGE EGG AND BEANS AND A CHEESE FLAN – THANKYEWWWW!” the barmaid screeches.

“I shared a dormitory with five other men,” Fripp ploughs on. “One from Alaska, two Americans, an Irishman, a Polish American and an Italian. . .” (“Heard it,” I’m tempted to interrupt.) “The Italian,” Fripp goes on, “would wake up most mornings at 3 am and fart sufficiently loudly to wake me up. The Alaskan had his bed next to mine. He was always rather depressed and unhappy. His head was hunched into his shoulders, like this. . .”

Fripp does an impression of a somewhat deformed Alaskan. The businessmen move nervously away from us.

“One of my favourite memories of Sherbourne,” he’s telling me now, “is of being in a trench, digging for a water main. There I was at the bottom of an eight-foot trench, which has taken two days to dig, with 28 other people, all of whom without distinction I detest – suddenly it begins to rain. And then a cheerful voice at the top of this trench as one looks up says, ‘Hello! We’re digging in the wrong place! The water main’s over here! You’ll have to start again.’

“It was marvellous,” he says with a note of truly sombre reflection, “to have one’s lofty ideas of oneself so deflated. I mean, I think everyone who went into Sherbourne thought that God had selected them uniquely and specifically to save the universe, so it was a very, very useful deflation.”

“LAST ORDERS, LADEEZNGENMEN, PERLEEESE,” the barmaid howls.

“Time to move on,” Fripp announces, so we do – to somewhere called The Salad Centre, where we have some herbal tea that tastes like it’s been strained through someone’s dirty socks and Fripp talks and talks and talks and I begin to feel even more strangely disembodied and start wondering if I am going to be stuck forever in this strange purgatory where I will have to listen to Fripp’s apparently endless discourse as eternity unfolds, Fripp’s voice haunting me lo until the end of all time. I stare blankly at him, unable by now to take in whatever he’s saying – something about “riding the dynamics of disaster” – reduced to mystical static that means nothing to me. On and on he goes, until the light starts to drain from the day, even as all life begins to drain from me.

We’re back at the station now, Fripp still talking. I want frankly to scream, beg him for a moment just to stop. But on he goes. I feel like setting fire to myself. Bile is rising in my throat. Where – oh, where – is my train?

“I’m currently working on a completely new theory,” he says, and I’m afraid he’s going to tell me what it is, which he does. “I’m working on the theory that Christ spent the missing 12 years of his life in Wimbourne,” he begins, at which point I can stand it no more and promptly vomit where I stand.

“Oh, dear,” says Fripp. “Might it have been the nut cutlets?”

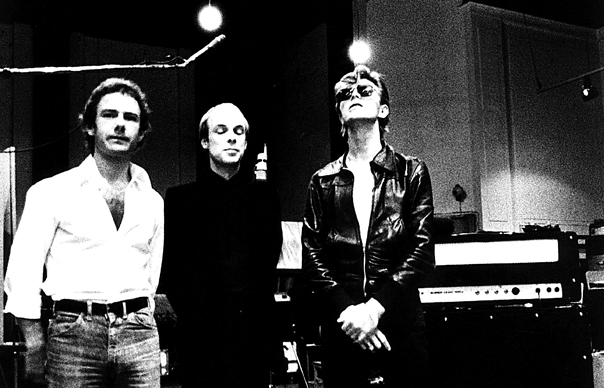

Pic: Michael Ochs Archives