In the latest issue of Uncut (Take 181, June 2012), out now, we visit Tom Petty at his California home to discuss the history of the Heartbreakers, why he's "a ridiculous control freak" and why the group are heading to the UK for the first time in 15 years – so it seems like a good time to check o...

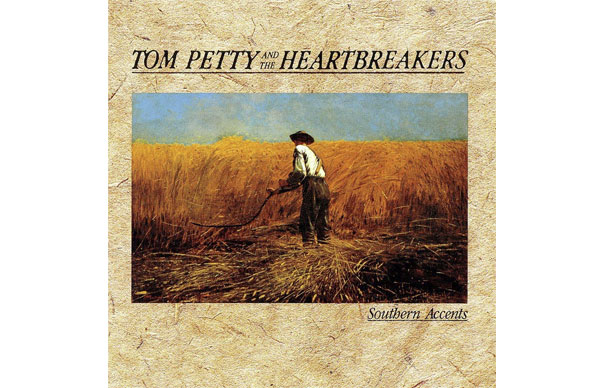

In the latest issue of Uncut (Take 181, June 2012), out now, we visit Tom Petty at his California home to discuss the history of the Heartbreakers, why he’s “a ridiculous control freak” and why the group are heading to the UK for the first time in 15 years – so it seems like a good time to check out this great piece by Adam Sweeting on Petty’s ‘lost classic’, 1985’s Southern Accents, from Uncut’s May 2004 issue.

_______________________________

If you were compiling a list of Southern Rock bands, you’d have The Allman Brothers, Lynyrd Skynyrd and The North Mississippi All Stars pencilled in pretty sharpish, and probably The Black Crowes, The Atlanta Rhythm Section and Molly Hatchet, too. Tom Petty & The Heartbreakers, however, might very well be absent, even though they originally hailed from Florida. After all, few outfits have become so identified with the sunshine, smog and

sybaritic lifestyle out west in California. And it wasn’t until the Heartbreakers were five albums into their career that Petty made a conscious effort to reconnect himself to his Florida roots with Southern Accents.

A decade earlier in 1974, Mudcrutch, as the pre-Heartbreakers were known, had loaded their gear into a VW van and set out from their hometown of Gainesville, Fla. for California and the prospect of a record deal. In hardly any time, they were fixed up with Denny Cordell’s Shelter Records.

The Heartbreakers landmarks usually go like this: taut and wiry debut album finds favour with a Britain in the throes of punk, Petty striking up a rapport with Elvis Costello and Nick Lowe. Follow-up You’re Gonna Get lt! pumps up the volume in a jangle-rock stylee. Then band enters Lawsuit Hell and bankruptcy, emerging triumphantly with raised-digit epic Damn The Torpedoes. Hard Promises cements Heartbreakers into mainstream, Long After Dark features band raging against the rockbiz machine… and then Petty decides to make a solo double album about his Southern background. He’ll call it Southern Accents.

Heartbreakers compilations always skate briskly over Southern Accents as if the Trackpicker-In-Chief was ordered to bury his head in inferior live tracks or selections from Petty’s later solo work. Maybe it’s because the finished album veered off at right angles to Petty’s original objective, or maybe it’s because it emerged from a dark and murky period in the band’s history, but the most interesting parts are airbrushed from view.

The album was recorded at Petty’s home studio in LA, though as he gradually invited his bandmates in to help out, it moved away from his solo concept and morphed into a Heartbreakers project. The decision to make the album at Chateau Petty proved ill-conceived, and as the sessions ground on cabin fever set in. Recreational drugs were consumed, day turned all too frequently into night, and partygoers stopped by at all hours. Petty himself was in some sort of mid-life creative crisis.

“Tom was dancing with the devil at that point,” says Heartbreakers drummer Stan Lynch. “I imagined he was going to go… Something was going to happen real bad.”

Although he was having no trouble knocking out songs, Petty couldn’t get a grip on the album’s direction. His exasperation came to a head one night while he was making the umpteenth attempt to mix opening track “Rebels”, a combined self-portrait and Civil War flashback. Petty vented his frustration on a nearby wall, violently enough to break a mass of small bones in his hand.

Eventually, Petty had to call in outside help. With Dave Stewart, who’d been invited to LA by producer Jimmy Iovine to work on a Stevie Nicks album but slipped into Petty’s orbit instead, he created the eccentric but effective “Don’t Come Around Here No More”, the plastic disco-pop of “Make It Better (Forget About Me)” and the bogus funk-rap of “It Ain’t Nothin’ To Me”. All these made the cut at the expense of a batch of songs much closer to the album’s original theme.

It’s as if the only way he could trip himself out of the log-jam was to force himself into an alien musical style, and the Stewart material sounds incongruous alongside the other tracks. The fiery and anthemic “Dogs On The Run” recalls the widescreen Petty of “Refugee”, and “Mary’s New Car” is built around a word-game lyric that lets the musicians paint whatever they like under it. Echoey vocal counterpoints, saxophone and a cool, floating beat make it one of the band’s most atmospheric creations.

As for “Spike”, a bit of panting-dog noise at the end suggests it might be about Tom’s family pet but the warm, rubbery feel of the playing and the way the musicians seem to be tiptoeing around each other in slow motion makes it more likely they were talking about stuff you stick in your veins. Petty’s vocal plays the ornery-Southern-motherfucker to the hilt and is positively chilling in its sneering delinquency.

The big set-pieces, “Southern Accents” and “The Best Of Everything”, end sides one and two of the LP release respectively. “The Best Of Everything” was originally written for Hard Promises a couple of years earlier, but when it didn’t make the album it became the germ for Southern Accents. Robbie Robertson created the sprawling brass arrangement, reminiscent of The Band’s Rock Of Ages live album and evoking an appropriate antebellum grandeur, and had the brainwave of inviting Richard Manuel to sing harmony. As for the twilight-zone ballad “Southern Accents”, Petty has always rated it as one of his most personal pieces.

It wasn’t until the release of the Playback boxset in 1995 that more pieces of the jigsaw fell into place, since scattered among the six discs were several discarded refugees from the Southern Accents project. “Trailer” was a wry account of a relationship cursed by narrow horizons and straitened circumstances, couched in bittersweet country-rock.

Petty reworked similar turf in “The Apartment Song”, duetting with Stevie Nicks over a jumping, hiccuping beat fired up by some sterling cowpoke guitar from Mike Campbell. The song was later reworked for a Petty solo album, Full Moon Fever.

If these omissions seemed baffling, the decision not to use “The lmage Of Me” (written by Wayne Kemp and a hit for Conway Twitty) was actionable. In concert, The Heartbreakers are apt to take a shot at anything from Ray Charles to The Louvin Brothers, and here they drop deftly into some sleek Western swing, gliding from the speakers like a silver streamliner hurtling across Texas.

There was also the Heartbreakers’ account of Nick Lowe’s “Cracking Up”, with Petty sounding ultra-dry and super-laconic. It was both a flashback to their first flush of success in England and perhaps a glimpse into their collective state of mind. Finally, there was a brisk acoustic version of “Big Boss Man”, Petty singing in a retarded slur as though his brains had been broiled by the Delta sun. Taken together, the missing songs could have added a wealth of nuance to Petty’s portrait of the South, and would also have showcased aspects of the Heartbreakers’ abilities which usually went unheard. Southern Accents might have been acknowledged as Petty’s masterpiece, instead of an intriguing failure dangling in conceptual limbo. But you could always get a copy of Playback and assemble your own bespoke version of it.