The usual complaint about political pop was that leftwing bands merely preached to the converted. In fact, there were crowd elements who remained resolutely unconverted, with avowedly anti-racist Two-Tone bands such as Madness and The Specials often becoming magnets for neo-Nazi skinheads.

“What was frustrating was that there were plenty of people in the audience who just liked the sound of the music and the look of the clothes,” says Jerry Dammers. “They didn’t particularly agree with the lyrics. In fact, ha ha, there were people in the band – and Terry [Hall] has been pretty clear about this on this a few times – who didn’t agree with the lyrics!”

Most astonishingly, some who lapped up the anti-Thatcher pop of the early 1980s now sit on the Conservative Party’s front bench. George Osbourne has expressed his love of The Smiths, The Jam and The Clash, as has Old Etonian David Cameron, who cites The Jam’s “Eton Rifles” as one of his favourite singles. Trumping them both is shadow spokesman for culture, media and sport, Ed Vaizey, who has come out as a fan of the SWP-aligned Redskins.

“I like passion, in politics and in pop, even if it’s misguided,” says Vaizey. “And I got passion from all those bands – The Specials, The Beat, The Jam, The Redskins. It’s become a cliché, but Thatcher was one of those Marmite figures – you either loved her or you hated her. Even those who hated her had to acknowledge that she was an iconic figure, and as such she became a lightning rod for dissent.”

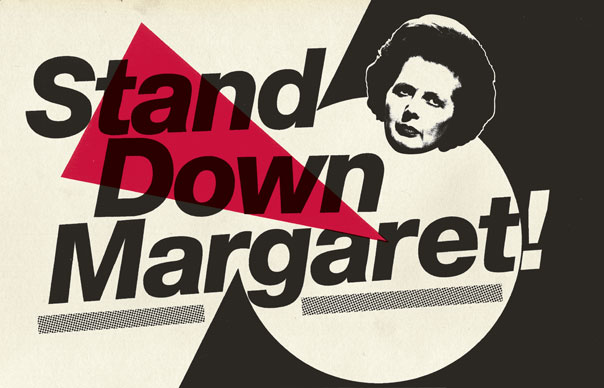

Pop’s most concerted effort to oppose Thatcher came in November 1985, when Billy Bragg and Paul Weller, together with MP Robin Cook, launched the Labour Party-funded initiative Red Wedge. A seven-date UK tour followed in early 1986, with a core group of Bragg, Weller, Dammers, Johnny Marr, Jimmy Somerville and Junior Giscombe. Another tour before the 1987 General Election added Matt Johnson, Captain Sensible, The Blow Monkeys and various leftwing comedians to the bill.

In retrospect, Red Wedge seemed to conclude pop’s dalliance with organised politics, largely because it failed to attract young voters. The 1987 General Election not only saw another Tory landslide, but also showed that Labour were still supported by fewer first-time voters than the Tories (34%, up from 29% in 1983, but still lower than the Tories’ 45%).

Political pop went into decline: the few anti-Thatcher anthems that followed were desperate, wearying fantasies of her death – Morrissey’s “Margaret On The Guillotine”, Elvis Costello’s “Tramp The Dirt Down”. That brief burst of positivist leftwing pop of the mid-1980s coinciding with Red Wedge (The Kane Gang, The Redskins, The Housemartins, The Style Council, The Christians) started to fizzle out, the messages of resistance drained from the lyrics until only the vestiges of retro soul remained.

“People became resigned to Thatcherism,” says Peter Hooton of The Farm. “In Liverpool around 1979 and 1980, people were angry, listening to The Clash, The Jam, The Specials. By the mid 1980s, that had been replaced by resignation. For most the 1980s, young unemployed kids in Liverpool were listening to Pink Floyd and Jimi Hendrix. Partly it was nostalgia for an age they felt was better, partly it was the amount of heroin that was sweeping through the city. You can’t really enjoy The Clash on heroin.”

By 1987, unemployment had been stubbornly stuck above three million for more than four years, with youth unemployment in excess of 60% in parts of Britain. “Ironically, it was the ideal culture for forming a band,” says Hooton. “You noticed that not just in Liverpool but all around the country. If you were in a band and you were serious about it, you certainly couldn’t hold down a day job. So you had this massive explosion of bands around the country rehearsing in the daytimes and then playing live at night. And, with the expansion in higher education, there seemed to be more venues for people to play.

”The irony was that very few of these bands were that political, even at a time that the NME, for instance, seemed to have become a Redskins fanzine. Liverpool might have been the country’s most militant and politicised city in the country at the time, but what pop did it produce? Frankie Goes To Hollywood! You can’t get much more escapist than that!”