As 1975 progressed, CBGB’s began to draw larger crowds. The club’s founder, Hilly Kristal, had settled a dispute with Village Voice and was at last able to advertise gigs. In July, he launched the Unsigned Band Festival, whose lineup included the Ramones, Television and Talking Heads. The festival was covered by the music press; the Ramones were getting noticed.

“I’d watched them develop,” confirms Sire Records producer Craig Leon. “By summer ’75 I decided it was time to get my bosses along to see them. The root of all these punk bands was The Fugs, who were poets and beatniks who played music, and that tie-in with the New York art scene and the folk tradition of New York – folk in the sense of music from the streets being played back to the people, like The Fugs and The Velvet Underground – was important to me. I saw the Ramones as an extension of that, as well as a return to the cool record of the 1950s, Sun Studio and Eddie Cochran. There was this raw energy and they were also hysterically funny. Plus they wrote catchy songs. It was all the things rock and roll wasn’t at that time. I didn’t see it as a breakthrough, just something that was radically different. We thought they would give Bay City Rollers a run for their money.”

Another admirer was Danny Fields, former manager of Lou Reed, the Stooges and The Doors who now wrote for Soho Weekly News. After prompting from Erdelyi – and a tip-off from fellow writer Lisa Robinson – Fields made the trip to the Bowery. “I was overwhelmed,” he remembers. “The first song I heard was ‘I Don’t Wanna Go Down To The Basement’. I thought it was a brilliant idea for a song. I’m not a lyric guy, but I couldn’t miss this one – it’s the only sentence in the song. I wanted to have a successful management venture because all my previous ones had been with lunatics, so I met them after the show. Meetings at CBGB’s always took place on the sidewalk because that way you could hear each other even if you had to kick the bums out the way. I told them I wanted to be their manager. Johnny said, ‘OK, but we need $3,500 to buy drums.’ I flew to Florida, told my mother I needed to make an investment and she wrote me a cheque.”

Fields enlisted a co-manager, Linda Stein – wife of Sire Records’ boss Seymour Stein. After her husband saw the band, Sire offered the Ramones a singles deal. There was a plan to record a compilation of CBGB’s bands called “New York’s Finest”, but Leon wanted more. “Seymour wanted to make two singles, but I said I could make a whole album for the same cost. What’s the point in setting up the Ramones for five songs when you can get an album? There had been inklings in the British press that something was happening in New York and Sire felt that if we could make a cheap album and get our money back in Europe it wasn’t a risky proposition.”

The Ramones entered Plaza Sound Studios above Radio City Music Hall to record their debut album in February 1976. Although Leon was producing, his guide was Erdelyi. “I was very conscious I was interpreting his vision. Tommy had the whole concept already planned. He designed the sets like one long art experience rather than a bunch of songs.”

Ramones was recorded in five days. “We had a very low budget so had to work quickly,” explains Erdelyi. “The first day we all had really bad colds so we had to redo the songs and lost some time there. It was hard to work with the engineers because what we did was so different they couldn’t work it out. We then mixed it in one marathon session. In the end, it sounded almost arty.”

That was precisely Leon’s intention. “Nothing about it was conventional,” he recalls. “Every track was done three-piece live, but there was considerable doubling, tripling, quadrupling of guitars. Johnny, Dee Dee and Tommy were all in different rooms, playing along to earphones. Tommy was playing to a visual metronome set at 208bpm because that was as fast as it could go, although for ‘I Wanna Be Your Boyfriend’ we slowed it down to 192.”

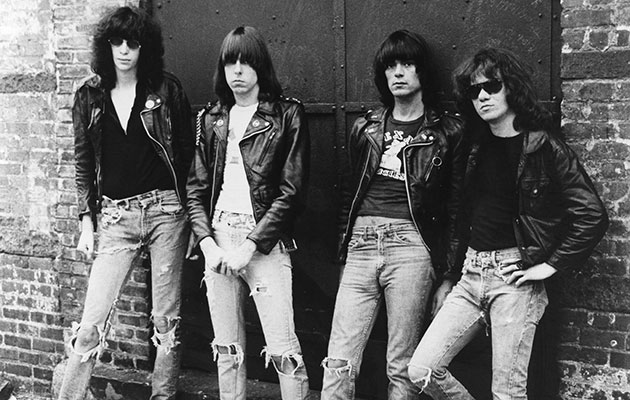

Leon mixed three versions – mono, stereo and the one released, which had “extreme separation, with guitars in one speaker, bass in the other and drums coming down the middle with vocals all around. It was meant to be high impact.” The album cost $6,300 and was packaged with Roberta Bayley’s photograph of the band slouching meanly against a brick wall – a happy accident, even if Leon had proposed just such an image, inspired by that on The Fugs’ debut. From the opening salvo of “Blitzkrieg Bop”, with Joey’s “Hey ho, let’s go” battle cry, this was a dramatic hello. Songs were belligerent, comic, romantic and autobiographic, often all at once, as with Dee Dee’s “53rd & 3rd”, which recalled his experiences turning tricks to pay for his continuing heroin habit. “I Wanna Be Your Boyfriend” was beautiful and yearning, “Now I Wanna Sniff Some Glue” gleeful, funny and dumb. The songs were deceptively simple – Richard Lloyd once tried to write a song with Joey, but discovered Joey’s guitar only had two strings because that was all he needed – supremely melodic and incredibly fast. “Their songs are sweet, they have great melodies, they are hummable and they are on those basic chords that often change in a strange place in the bar,” says Kaye. “When you add Joey’s sense of romantic longing, there’s a real sense of desire in those songs.”

Although the album was well-reviewed, it sold poorly and was ignored by radio – a pattern that would become familiar. But Leon says that “where radio took a chance, you could see these little pockets of bands popping up – in Ohio, in Athens, Georgia, and in Europe.” He sent a copy to Paul McCartney, with a note that the band had been named after him. “He wrote back saying his mind was blown, he couldn’t believe it,” says Leon.

In July 1976, the band landed two gigs supporting The Flamin’ Groovies at the Roundhouse and headlining Dingwalls in London, where the first stirrings of punk were taking shape. “We knew that we had sold out these places so we had an idea something was going on,” says Erdelyi. Fields recalls the three-day trip with astonishment: “They played for 3,000 people; their biggest audience before had been 50. There were people lining up to meet them, to sleep with them, to sleep with me. The dressing room was full of people from The Clash, The Damned and the Sex Pistols – Johnny Rotten had to climb up knotted sheets to get through the window. They were amazed that a band could put out a record like this. Johnny told Paul Simonon, ‘We suck, we can’t play. But don’t worry, just do it.’”