To coincide with Sufjan Stevens' current run of American tour dates, here's our extensive interview with Stevens from Uncut's June 2015 issue. ---------- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3vj9s0U2U2o The Prodigal Son A very intimate interview with Sufjan Stevens. How road trips, rodeos, all-ou...

To coincide with Sufjan Stevens’ current run of American tour dates, here’s our extensive interview with Stevens from Uncut’s June 2015 issue.

———-

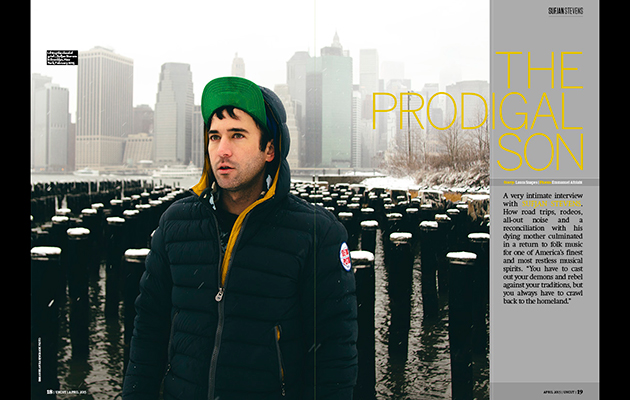

The Prodigal Son

A very intimate interview with Sufjan Stevens. How road trips, rodeos, all-out noise and a reconciliation with his dying mother culminated in a return to folk music for one of America’s finest and restless musical spirits. “You have to cast out your demons and rebel against your traditions, but you always have to crawl back to the motherland.”

Sufjan Stevens is wearing two hats. A woolly blue number sits atop his green trucker cap, whose peak he has bent flush with his forehead, the goofy effect belying his 39 years. At one point when describing his sprawling approach to music, he has to stop himself from saying he wears a lot of hats. “I – accessorise a lot,” he says instead, laughing.

On an icy early February morning, Stevens’ Brooklyn office is temporarily homing the accessories from his most recent stage show before they’re transferred to his storage facility. Last week, he finished a six-night run at the Brooklyn Academy Of Music, where he performed Round-Up, leading a small ensemble in a peaceful, drone-oriented soundtrack over slow-motion footage of a traditional Oregon rodeo. It is not entirely clear what role the bag of gold foil fringing, hula-hoops wrapped in silver tinsel and the painting of a white horse played, but Stevens found a strange satisfaction in the project. “It’s really non-musical,” he says. “I really wanted to evacuate from the artistic experience and become almost like an observer, as a musician.”

He’s contemplating its viability as a touring production, and may eventually record it, as he did with 2009’s The BQE, another BAM commission that focused on the freeway five blocks up from his office. But these projects often feel like distractions from the main event: the acoustic reveries of Seven Swans, Stevens’ meticulously realised song-suites about the states of Michigan (2003) and Illinois (2005), and his last album proper, 2010’s The Age Of Adz, a sprawling electronic record that engulfed the listener in his state of cosmic panic.

Being a fan of Stevens is somewhat predicated on accepting his large hat collection. It was barely surprising to see him make two hip-hop records with rapper Serengeti and producer Son Lux. A 161-minute-long 2012 Christmas release felt as predictable as socks and clementines. But the difference with Round-Up is that Stevens intended it as a distraction from the music he had been writing. The songs he almost abandoned became Carrie & Lowell, his seventh studio album: not one he planned to make, but an attempt to survive the death of his estranged mother and the ensuing two years of grief.

“For so long I had used my work as an emotional crutch,” he says. “And this was the first time in my life where I couldn’t sustain myself through my art. I couldn’t solve anything through my music any more. Maybe I had been manipulating my work over all these years – using it as a defense mechanism or a distraction. But I couldn’t do that any more, for some reason.”