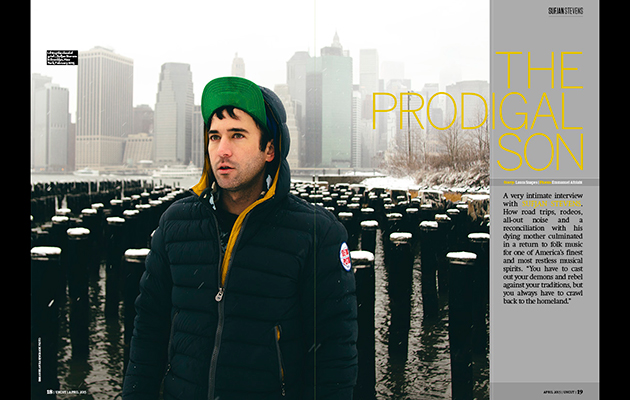

To coincide with Sufjan Stevens' current run of American tour dates, here's our extensive interview with Stevens from Uncut's June 2015 issue. ---------- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3vj9s0U2U2o The Prodigal Son A very intimate interview with Sufjan Stevens. How road trips, rodeos, all-ou...

It was while Stevens was travelling around the US that he witnessed Oregon’s famed Pendleton Round-Up, one of the world’s 10 biggest rodeos. Beguiled, he commissioned filmmakers Aaron and Alex Craig to capture it; when Stevens reviewed the footage, he realised there was a viable idea there, which he took to the Brooklyn Academy Of Music last summer. They commissioned a January 2015 run. “I had to scramble quickly to put it together,” says Stevens. “There was so little time to do it that I didn’t even stress. And actually the footage was so fully realised that I didn’t feel the need to wrestle out meaning or substance from it. I just felt like a steward.”

Embarking on Round-Up was a gamble: working on The BQE in 2007 induced within Stevens a profound existential and artistic crisis about the purpose of art after he had spent nine months attempting to wrangle significance from 35 miles of concrete. “It didn’t really have any meaning in the end,” he says. “It was a struggle.”

Around that time, Stevens was struck with a chronic, mysterious illness. Once had had recovered, he wrote The Age Of Adz as an exploration of his creative and physical wellbeing: “the purity and authenticity of voice versus the desire for discovery and innovation,” he says. “Wanting to seek out new worlds and also wanting to know myself more fully and more clearly. Those two experiences or creative states of being don’t always cohabitate well.”

Having written the potential follow-up to Adz in the midst of depression, Stevens felt he lacked “responsible authorship for the material”. Round-Up seemed like the perfect fresh start, so he abandoned the “30 or 40” grief-stricken songs he had been disparately working on. “I was finally over my depression and over my grief as well, and entering a new season of hope,” he says. “The rodeo was the perfect kind of distraction because it’s meaningless – it was a project based on aesthetics and design and beauty and meditation, it was very clearly organized.”

His friends, however, weren’t about to let him ditch the other material. “Anybody who heard that album was like, ‘you have to put this out yesterday’,” says composer Nico Muhly. “I have like, 60 emails where I was literally like, ‘put it out’, both as subject and content.” Manhattan-based composer Thomas Bartlett got in touch last summer to ask what was going on with the music. Stevens invited him to his studio to hear it.

“He said he felt a little bit lost with it, that he had been working on it for some years and didn’t really have a sense of where the record was going, or if he had anything at all,” says Bartlett, who insisted that Stevens make him a CD of rough mixes that he would take on his summer holiday. “There were some outliers: electronic things, or sometimes four versions of the same song, with different lyrics or a radically different approach musically.”

There was one aspect to cull immediately. Michigan and Illinois were the first entries in a project whereby Stevens apparently intended to document the historical quirk and emotional resonance of all 50 states in song. He eventually abandoned the idea, calling it a promotional gimmick. But Carrie & Lowell almost became Oregon until Bartlett talked him out of it. With no criticism implied, he calls Stevens’ state records “complicated misdirection and an architecture by which he could actually write about himself. I asked him to let go of the idea that this was an Oregon record and just allow it to be what it really feels like it is, which is a very, very personal record.”

Bartlett returned from vacation with the tracklist, made Stevens change some titles and vocals, and remixed it. “It all came together within a month,” says Stevens. “He doesn’t fuck around. I wouldn’t have wanted to have made such a direct and depressing album, but he called me out on my bullshit and said, just be honest to this experience and stop trying so hard. I don’t think I would have made this record without him.”