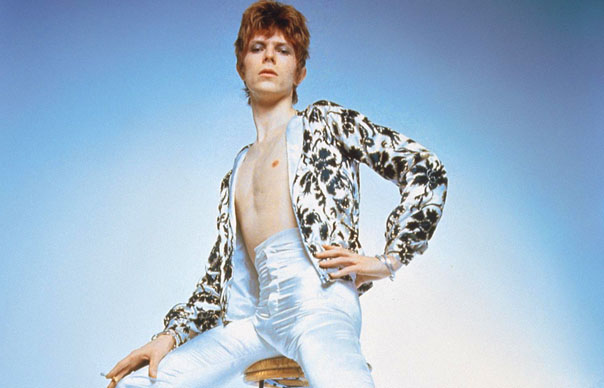

The new April issue of Uncut, out now, features David Bowie peering from the cover in his guise as sleazy space-star Ziggy Stardust. To celebrate this look at Bowie’s greatest creation 40 years on, here’s a fantastic piece from Uncut’s 18th issue, in November 1998, in which Chris Roberts looks back at the glammed-up, transgressive superstars who changed his adolescent world.

TWENTIETH CENTURY BOY

In 1972, Britain joined the Common Market, Richard Nixon became the first American president to visit China, Arab terrorists turned the Munich Olympics into a bloodbath and Oscars were won by The Godfather and Cabaret.

Like, I could’ve cared less.

For into this world of On The Buses and Lift Off With Ayshea, of much fuss about some guy named Tutankhamen and newly decimalised currency, came a psycho-cultural force so irresistible, so spectacular, that one could only roll over and experience puberty as an absurdly hallucinogenic riot.

Into this world came strange news from another star, came men singing of cops kneeling to kiss the feet of priests, and of queers throwing up at the sight of that, and of girls who were slim, weak, windy and wild, and had the teeth of the Hydra upon them.

Into this world came Glam Rock.

Glam Rock, like first love, never died for me. Actually, first love did die: I was 11, and threw a brick through her parents’ front window; doubtless a formative experience. But throughout Glam Rock’s ascent and decline I hung in there, loyal to a fault, like a party-crasher who relishes every last twitch and shiver of the hangover, like a man addicted to the dysfunction and push-me-pull-you pathos of a doomed affair. A Creamed Cage In August by Zinc Alloy And The Hidden Riders Of Tomorrow? A true magnum opus. “The Cat Crept In” by Mud? It rocks. “Saturday Gig” by Mott The Hoople? A tear in the eye. This rush of exuberant, narcissistic, electrifying records and poseurs only really went under when Bolan’s crash moved from metaphorical to physical, and the bopping imp landed the Early Death kudos. A month earlier, he’d told Steve Harley, ‘‘I’d hate to go now. I’d only get a paragraph on page three.”

He was wrong, as he often was, and this was part of what we loved about him. (1974’s Zinc Alloy…, the last great Bolan album, not content with asking, “Whatever happened to the teenage dream?”, included the couplet: “Do they have sickness in society?/Do they have glitter crap gaiety?” The front page of the Evening Standard of Friday, September 16, 1977 which broke the news might, in one way, have gratified him. It was dominated by a picture from his cheeky, diamond-eyed prime: “CRASH KILLS MARC BOLAN: Purple mini driven by girlfriend hits tree in Barnes Common, kills rock star”. On the bottom right-hand corner of that page, in a minuscule box, a much smaller headline: “MARIA CALLAS FOUND DEAD IN FLAT.” When the history of the century’s music is written, it seems probable that Callas, arguably the greatest, most emotive singer of any century, will be granted a more earnest appraisal than the man who wrote “Purple pie Pete, purple pie Pete, his lips are like lightning, girls melt in the heat, yeah!” On the day, though, nobody doubted that the Standard had its priorities right. Even on the slippery slope, even after singles as dodgy as “New York City” and ‘‘I Love To Boogie”, Bolan remained a fey, frolicsome figurehead for a pop phenomenon of stellar scale and impact. He would’ve loved knowing that, even a month after Elvis Presley’s death, he’d outshone, in the popular imagination, the Diva Assoluta…

HANG ON TO YOURSELF

Oscar Wilde asserted that we are never more true to ourselves than when we are inconsistent. If, in the early ’70s, you were leaving childhood and entering adolescence – that awkward phase when the potency of cheap music is most likely to get you in the groin in any era – then, boy, were you true to yourself. Swallowing whole a movement propelled by a satin-jacketed corkscrew-haired elf and a bisexual alien in a Japanese nappy with no eyebrows, one could easily become confused. Only decades on can it be fully appreciated that pop music is not always, if ever, this edgy, subversive and exciting.

Todd Haynes’ magical Velvet Goldmine, a Nic Roeg/Ken Russell fantasy, is blatantly based on Ziggy and Iggy and Showy Bowie and Loopy Lou, whatever the director’s opt-out disclaimers. By accident or design (I only suspect the former because his previous, critically-acclaimed films, such as Safe and Poison, have been so unutterably atrocious), and greatly assisted by the flawlessly contrived music (Shudder To Think, sodden with the spirit, sing of “starships over Venus”), Haynes catches the tricksy essence of Glam: the often ham-fisted flirting with issues of identity and gender, the hatred of all things worthy–but–dull, the denial of any social, economic or theological cause but self–promotion and astral ego-projection, the greedy needy lust for fame.

It may have been punk that said never trust a hippie, but it was Glam that said never even be seen in the same building as one, it’s bad for your image.

It’s a shame that Haynes overindulges his own sexual preferences in the film, with all the main characters unequivocally gay or bisexual (as far as you can be unequivocally bisexual). The funniest and perhaps most radical thing about the Glam Rock era which, coming several years before the mass advent of video, made Top Of The Pops an indecently powerful parochial semiotic, was the way in which it influenced a generation of heterosexual boys and men to dress up like moist and fragrant gardenias.

Ridicule, as Adam Ant later whooped, was nothing to be scared of.

It was entirely routine for classmates to sit after football practice adorned in the most fey and billowing of shirts, glittery stack-heeled shoes, dangly earrings and inexpertly-applied eye shadow, while butchly exchanging tips on how best to see down Melanie Thomas’ generous blouse. No dichotomy was perceived in this double standard, though one was frequently perceived, behind the sand dunes, down Melanie’s blouse. The dandy, in 1972-3, walked hand in hand (as it were) with the overground lad.

It’s difficult now to gauge how sensational David Bowie’s declaration of bisexuality to Melody Maker (“Hi! I’m Bi!”) seemed at the time, with subsequent generations of stars adopting the ploy as an industry standard. Madonna has claimed to possess the soul of a gay man inside a woman’s body; Suede’s Brett Anderson equally hilariously touted himself as “a bisexual who’s never had a homosexual experience”. The gay male is a common enough cuddly uncle/flatmate figure in mainstream movies and sitcoms; the gay female, even if she has to go through Ellen high water, will catch up. But back then, Bowie’s arch scam (for scam it chiefly was) probed under rocks, tapped into irrational fears, taboos and sinister psychological hang-ups. For most impressionable fans and camp (sorry) followers, it was an insincere handle, a “mere” style statement on which to hang the fun-fuelled desire to dress up like a peacock on LSD.

This dovetailed beautifully with Glam’s urge towards the celebration of oneself as a star, with which great levelling intention it presaged punk. Punk, however, didn’t distrust the earnest, or, indeed, clamour for glamour. Punk struck me as a bit grubby, a bit spit and sawdust. A bit real. Heaven forbid. Reality was never a friend of the Glam rocker. Lou Reed, who with The Velvet Underground had always worn black so that films could be projected onto him, was urged by Bowie’s wife Angie to dress more adventurously to promote the aptly-named album, Transformer. He threw himself into the challenge, adopting an alabaster-faced, black-eyelinered “phantom of rock” persona. He said something that everyone was thinking at the time, a time when “Walk On The Wild Side”, with its lyrical cast of transvestites, lowlifes and speed freaks, was sharing the early ’73 airwaves with Donny Osmond and Peters & Lee. “I realized,” he said, “I could be anything I wanted.”

That was the thing. That was the rallying call, the vision, the inspiration. Even as a bewildered, uncomprehending 12-year-old wanker in the provinces, you could be anything you wanted. Anything. That was the beautiful lie.

RE-MAKE/RE-MODEL

At the dawn of the’70s, rock, self-important and self-conscious only in terms of devout muso noodling, was disappearing up its own back passage, with such flatulent grizzlies as Jethro Tull, Emerson Lake & Palmer and Deep Purple huffing and puffing to be the most stoned, the heaviest. The option was navel-gazing, introspective singer/songwriters. A new generation of teenagers craved a lightness of touch, a letting off of steam. “The fans are fed up with paying to sit on their hands”, said Slade’s Noddy Holder. “They want a party atmosphere.”

At the tail end of ’71, T-Rex’s Electric Warrior went to No. 1. Although it was replaced after six weeks by Concert For Bangladesh, the hippies’ death throe, it regained pole position, and in ’72 T-Rex became the first band since The Beatles to achieve three No. 1 albums in the same year. The next 18 months saw these charts dominated by Bolan, David Bowie, Roxy Music, Slade, Rod Stewart, Elton John and Alice Cooper, all of whom were either kooky-monsters of Glam Rock or shrewd enough to cruise in its slipstream. Slade were a quartet of distinctly unfeminine Brummie bruisers, whose terrace choruses and self-mocking sense of humour (guitarist Dave Hill boasted the highest heels and a Bentley with the plate YOB 1) gave them a relentless stream of massive Glam–with–chips anthems. Stewart and The Faces briefly glammed up their all–boys–together party games and stumbled on a fleeting wit with songs like “Maggie May” and “Cindy lncidentally”. Reg Dwight, ever the parasite, found an excuse to don the clobber by hacking out a relevant riff on “Saturday Night’s Alright For Fighting”, while Alice (aka Vince) introduced Hammer horror trappings to the OTT theatrics of Glam, molesting snakes and beheading dolls as accompaniment to such banger cute teen protests as “School’s Out” and “Elected”. The triumvirate, though, was Bowie, Bolan and Ferry. There’ll always be some debate over which of the prettiest stars Bolan and Bowie was the father of Glam, which the son, but Ferry was definitely the holy ghost. Academics will continue to overstate the significance of Brian Eno’s contribution to Roxy Music. I can assure you that the average sparkle magnetised youth at the time of their ’72 debut album was no more fascinated by the fringe keyboard player’s twiddling of knobs than by Andy Mackay’s innovative use of saxophone reeds. Eno dressed the part, but so did Manzanera and the rest. Ferry, however, sang of the future and the past, of sci-fi and romance, of something wished-for and something lost, in the voice of F Scott Fitzgerald starring in Casablanca.

You have to remember the teenage fan leaps insatiably on illusion and fantasy – especially when it mythologises love and sex – like a starving piranha with seven thousand deadly fangs. We wanted swooning, not science. Experimental synthesiser sounds? Maybe we’d get into them when we were all growed up.

As these artists were deconstructing the stage act and rehabilitating the album – Bowie realigning the relationship between Star (exhibitionist/actor) and Fan (voyeur/inventor) – the 45rpm pop single became a vessel of buzzy adrenalin and swagger not glimpsed for years. Serious rock giants like Led Zeppelin had decreed that the mere single was for pop tarts. A new breed agreed heartily, thanked them for their diagnosis, and proceeded to shake their tinselled tushes to three glorious minutes of crass, flashy sass. Among these, customising the Bacofoil-suit-and-bizarre-plumage panto aspects of Glam and hamming them into the nation’s homes, were Gary Glitter, who beat his matted chest and proclaimed himself the leader of the gang, Wizzard, a vehicle for the studio genius of rainbow–thatched Roy Wood. Mott The Hoople, Steve Harley’s Cockney Rebel, David Essex, Alvin Stardust, Barry Blue, Arrows, Hello, the emerging pretenders Queen and the inspired, genuinely idiosyncratic Sparks. The Bay City Rollers, often erroneously annexed to Glam, were a different, inferior jape.

Each had moments of vulgar genius (Harley’s tarnished reputation in particular is well served by Velvet Goldmine), but the Holland/Dozier/Holland or Stock/Aitken/Waterman of the era were undoubtedly songwriters/producers Nicky Chinn and Mike Chapman, whose cordite constructions for The Sweet, Mud and Suzi Quatro were the trash aesthetic in excelsis.

Streamlined barrages of stomping Burundi drums and raw, pithy guitars such as “Ballroom Blitz’. “Hellraiser”, “Teenage Rampage”, “Tiger Feet”, “Rocket”, “48 Crash” and “Devil Gate Drive” were sneered at by mature critics, but were a vital, visceral component of my peers’ musical and even sentimental education. Doubtless they infected their victims with chronic impatience, peripatetic attention spans, and a lust for cheap thrills. Furthermore, they still sound more knowingly numbskull than 99 per cent of punk rock’s avowed avengers. The Sweet brought some high comedy to Glam’s history by not only plagiarising the same Yardbirds riff for “Blockbuster” as Bowie did for “Jean Genie”, but also keeping the hipper record from the No. 1 spot in January ’73.

“Blockbuster” remains the first, last and only chart-topping single to get away with shouting, “Aw, fuck!” Listen closely to Steve Priest’s cameo lost-the-plot exclamations. This band, incidentally, thought nothing of appearing on Top Of The Pops as gay Nazis. Pouting bassist Priest ranted furiously at the television producer who didn’t agree that his turning round after the opening bars of “Ballroom Blitz” to reveal the phrase “Fuck You” emblazoned on his back was a sound idea. Chinn had one minute to cajole Priest into acquiescing. And the chutzpah of that “WE WANT SWEET!” section that fronts “Teenage Rampage”!

By the time the Chinnichap combos were burning out (reduced to heavy metal pastiches or scampi-in-a-basket cabaret), Bowie and Roxy had moved on to other, resiliently ambitious, modes of expression. Mixed-ability cash-in movies such as Born To Boogie (Bolan), Slade In Flame, That’ll Be The Day and Stardust (Essex), Remember Me This Way (Glitter), Never Too Young To Rock (Mud, Hello, Rubettes, Glitter Band) and DA Pennebaker’s Ziggy Stardust concert film had sped up the process. Glam, nothing if not voracious, was devouring itself. Even Bolan, in ’73, was declaring, “Glam Rock is dead. It was a thing, but now you have your Sweet, your Chicory Tip, your Gary Glitter. What they’re doing is circus and comedy.”

Or Glitter Rock, as some would have it. The basic sound: hefty Diddley beats, cranked-up Cochran riffs, Duane Eddy/Link Wray delayed twangs, and wacked-out doggerel with insanely high multi–tracked backing vocals, today smacks of the facile and flippant. Or of a mean-as-snakes, razor-sharp, minimalist purity, depending on your attitude. I was always sold on shiny baubles, sexy surfaces, the truth of trinkets.

On imitations of joy.

THE BOGUS MAN

In Velvet Goldmine, Christian Bale gamely plays Arthur Stuart, an ex-pat reporter who’s researching an anniversary article on the faked assassination of rock star Brian Slade’s alter ego, Maxwell Demon. While Haynes says this isn’t “necessarily” based on Bowie’s killing-off of Ziggy Stardust: hey, let’s get real. Just this once. Arthur is compelled to excavate a past he’s left behind.

Brian Slade, and Glam Rock in general, had been a religion to the younger Arthur, who was sucked by its allure into a vortex of hedonism and decadence, ultimately being “gently fucked” by Curt Wild, who whispers, “I will mangle your mind.”

But that’s the movies for you. While I may well be a jaded hack looking back on a craze/crusade that shunted me (with my full co-operation) across a few airstreams, I have not as yet engaged in robust anal sex on a rooftop with a bewigged, lggyesque Ewan McGregor, so the resemblance, happily for me, ends at a certain point.

Still, the experience of meeting and interviewing David Bowie in LA gave me a rare case of prematch nerves. Both times. He was in the event(s) charming and unaffected (unless he affects unaffectedness, which is, of course, very likely), and a little verbose, which is fine by any interviewer. Naturally, I interrupted him long enough to press a copy of my own recently-recorded album into his palm.

Iggy Pop is an absolute diamond, who stunned me with his intellect, then turned up at my birthday party and within seconds was chatting up girls with the killer line, “Hi, I’m James.”

Another time I had to leap athletically into the road and wrench him back as he was about to walk blithely under a speeding car, and thus earned the right to claim I once saved Iggy Pop’s life. We both ended up arse-over-tit on a Piccadilly pavement, giggling dementedly. Me and Iggy, ha, ha, ha.

On the whole, I think I prefer my pert little experiences of meeting my idols to Arthur’s more operatic, sweaty, life-buggering-art epiphany.

The most poignant moment of the film comes when, accosted by misguided fans, Arthur says, “No, sorry, I’m just a journalist. Perhaps you’d like to keep my press pass, as a souvenir?” Just a journalist. The chagrin! “Glam gave me a sense that there was more to life than life on Earth,” this journalist told Melody Maker in ’92 while having a go at being a pop star. “That you could shoot for the stars, and at least hit the crossbar.”

There’s a blind-spot part of everybody, however sentient, however cynical, which thinks they could make it all worthwhile, could play the wild mutation, could fall asleep at night, as a rock’n’roll star.

To a certain generation this is because Ziggy Stardust told us it was so.

THE KING OF THE MOUNTAIN COMETH

Head of Creation Records, Alan McGee, says that “the reason I got into rock’n’roll is because I saw David Bowie on Top Of The Pops with a bright blue acoustic guitar playing ‘Starman’ in July, 1972, and Mick Ronson on 10inch platforms, bending over, giving the guitar fellatio. I was gobsmacked. My reaction was part wanting to be David Bowie and part sexual arousal. I have since discovered my sexuality, and bizarrely it’s not towards men. I can honestly say the first person who turned me on was David Bowie. Respect to Ziggy Stardust.”

On June 6, 1972, curiously enough my 12th birthday, David Bowie released The Rise And Fall Of Ziggy Stardust And The Spiders From Mars. It got to No 5. It was the first record I ever bought. My dad embarrassed me by coming with me to the shop. With hindsight, he may have been concerned. Imagine: your boy suddenly becomes obsessed with a gay Martian in a green jumpsuit who hangs out in phone boxes – like, what’s that about? Certainly, he seemed relieved when pictures of Suzi Quatro and Liverpool FC joined those of Bowie, Bolan, Ferry and co on my bedroom wall. Next, I bought scratchy second-hand copies of Bolan Boogie and Electric Warrior, the two albums which confirmed T. Rex as a crackling, ecstatic pop entity, no longer hippie warblers. T. Rex sold 16 million records in their first 14 months (The Beatles, in the equivalent period at the beginning of their success sold five million). At one stage, four in every hundred singles sold in Britain were by T. Rex. They had wonderful blue labels with a picture of Marc and the T. Rex logo in red. My friends and I would believe that in buying them, we were helping Marc get to Number One. We didn’t then know that the records that sell the most are the ones which the record companies have decided will sell the most. This was something we wanted, something we cared about. For one thing, if he was No. 1, he had to be on Top Of The Pops.

Bolan and Ziggy killed the ’60s for us. They killed them good’n’dead until the majors’ business acumen brought them back. They charted a map of style and in technique for white rock bands that was still being consulted, with equal degrees of reverence and shock, in the early ’90s. The ’60s meant nothing to us. We didn’t remember them and we weren’t there. I have never fully got over this prejudice. Dylan, “the artist of the century, our Keats”, looked and sounded like exactly what Glam Rock, with its breath of fresh hair. had come, to blow away.

Ziggy Stardust was, according to Cashbox magazine, “an electric age nightmare, a cold hard beauty – an album to take with you into the 1980s.” Charles Shaar Murray wrote that, “as an object lesson in media manipulation it eerily presaged Malcolm McLaren’s Sex Pistols adventure, and as a blueprint for a generation’s capacity for self-reinvention, it marked the turning point between the worlds of hippie and punk”. For David Fricke it was “a marvel of genetic pop engineering, a brilliant and authentic collision of classic rock’n’rolI extremes – erotic frenzy, gender confusion, celebrity arrogance, private dread, apocalyptic fear”, and featured “Bowie’s star-crossed glam-Christ”. The NME reckoned: “Bowie is our most futuristic songwriter, and sometimes what he sees is just a little scary.”

Bowie himself later said. “I wasn’t at all surprised that Ziggy Stardust made my career. I packaged a totally credible plastic rock star – much better than any sort of Monkees fabrication. My plastic rocker was much more plastic than anybody’s.”

It was what ironic icon Ziggy s uggested that rocked our world. That first song, “Five Years”, where the news had just come over that earth was really dying… what a way to start! The beginning of your love affair with music is the end of the world. Now that’s guaranteed to give the listener a grandiose sense of self-importance. This melodrama carried through, past the queer throwing up (my, how we analysed that), to the line that coloured your solitude for the rest of your life: “And it was cold and it rained, so I felt like an actor…”

Over ascending chords, this had such an overwhelming effect on my peer group that we were all instantly the stars of the movies in our heads and, frankly, Yes, Genesis, ELP, Pink Floyd and all Americans never stood a chance. Sure, if you liked them, you didn’t get called a poof. They were “proper” musicians. But who could like them? We were too busy making love with our embryonic egos, or buying 20 Embassy between four of us so that time could take a cigarette and put it in our mouths. And when your head got “all tangled up”, as it does at that (and, let’s face it, any) age, you were “not alone”, because Ziggy said so.

Which pretty much made Ziggy God in a godless world, I guess.

Interesting factual aside: most of the album was recorded live in autumn ’71, before the release of Hunky Dory. Bowie planned ahead. Originally it wasn’t going to include “Starman”, “Suffragette City” or “Rock’n’Roll Suicide”. It was going to include “Velvet Goldmine”, which ended up on a B-side. Bowie has refused the use of any of his songs for Haynes’ movie, preferring to keep them in stock for his own planned Ziggy revival film, 25 years on from the “retirement” of the persona which gave him the springboard to shuffle and search through some of the most incisive, cold, scorched music and imagery of our times.

The ICA in London staged, this July, a tribute to the quarter-century anniversary of that “Rock’n’Roll Suicide”. They had the gall to present this as conceptual art. It wasn’t. It pissed on our memories. It was a covers band, and until we were on our fourth or fifth pint, we thought it was bollocks, after which it was funny. But I liked this, from the programme: “Ziggy bore himself, defined himself, faked himself and killed himself in a surge of creative excess. Nothing related to a reality anyone knew, yet generations then and now bought in unconditionally to a way of life that can only be played out in full onstage.”

As the acid house decade has done away with stars (how the ravers need a crash course!), and Oasis and others have insisted that stars are just thick blokes in anoraks anyway, we’ve been shown the little old man working the levers behind the curtain in Oz. It’s been of late a lean period for fantasy, mystery, the indefinable.

Ziggy really was something else.

SOUL LOVE

For those of us who “never got off on that revolution stuff” and invented the term “dad-rock” when referring to The Beatles, Stones and Beach Boys, Bowie had the nous to go on to be the single most important and influential rock performer. When he became a white soul boy, so did we.

Aladdin Sane and Diamond Dogs could be considered Glam albums. The former filtered in wired impressions of cracked Americana while hooking us up with that larger-than-life lightning-bolt make-up. Was he perhaps, we mused, Zeus? The latter moved towards an arch Gothic, was ambitious and spooky, threatened real emotion in bursts. Pin-Ups, a collection of Mod covers (The Who, The Kinks, The Merseys) invited us to accept that maybe the ’60s weren’t complete bunk after all.

As did Bryan Ferry’s These Foolish Things, which even made us re-evaluate Dylan (and cleverly repositioned Ferry in the marketplace as a lounge lizard, as opposed to an ironic, post-modern, lounge lizard). “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall” may have been written by an old fur-face in jeans, but it was a hypnotic, delirious stream of intense imagery. We would wriggle under the mesh fence and bunk off school at 1.15 every day to hear it as it was Record Of The Week on Radio 1.

This was a seminal single to a Glam fan: it seemed to be about a guy who’d been everywhere and done everything but understood nothing. It testified about other worlds and lifestyles and dreams. We signed up for those dreams. It’s easy to sell pop music to teenagers, because to paraphrase the glamorous WB Yeats, if you tread on their pop music you tread on their dreams. Cunningly, with Machiavellian manipulation, it comes to represent escape from drudgery and school and no fun and no sex and no idea. It’s The Other. It’s sure fine-looking.

The worship of celebrity is a substitute for romantic love, which has itself been defined as the need to evade the self and immerse in another, a projection, however deserving or unworthy. So you give the star your loyalty, your money. You pay your tithes.

Bowie knew this, and stayed thin and hungry. Bolan did not. He drove a Rolls-Royce because it was good for his voice. As Mark Paytress wrote in his recent book, Ziggy Stardust, “Bolan enjoyed his stardom: Bowie (or Ziggy) critiqued his.”

A week before his death, Bolan recorded the last in the series of amusing childrens’ TV shows he’d been reduced to (although he salvaged some “credibiIity” by championing punk rock within its confines, and setting himself up as its “godfather”, hanging out with The Banshees and Generation X and having The Damned support him on tour). This edition of Marc featured old friend/rival Bowie as guest star. Bowie, gaunt and clean-cut handsome, premiered the song “Heroes”, demonstrating the healthy, advancing state of his art. Then the pair duetted on “Standing Next To You”, a little (and to this day enigmatic) something they’d knocked together earlier. They were just into the first verse when Marc tripped on a cable and fell off the stage.

Cue credits.

“Could there have been a more painfully symbolic end to the Electric Warrior’s career?” asks Barney Hoskyns. If Bowie attracted the cerebral (or what passes for it in 12-year-olds: let’s say he sparked imaginative connections), Bolan aroused the physical. Though historians will tell you his was standard three-chord rock played loud and in-your-face, I hear it as pure funk. When T. Rex play, it’s like tiny electrodes, fixed to my body by crafty Lilliputians in 1972, causing my legs to suffer chronic delusions, such as that they can groove foxily to music by white folk.

Soon, Marc was bigger than air. “Telegram Sam” and “Metal Guru” felt like cascades of sensual bliss. We’d play each one a hundred times. Then we’d go to someone else’s house and play it a hundred times on their record-player, to see if it was any different. That intro to “Metal Guru” – we’d never heard anything like it. Actually, we’d never heard anything much, but why tarnish an important rites-of-passage tale?

As Glam eventually became a short cut to the Top 10 for a bunch of cheerful clowns, it tarred and feather-boad Bolan, who, having failed to break America while neglecting his British fans, clung to coke and cognac and watched his preeminence slip inexorably away.

DO THE STRAND

The notion of the dandy (rather unsatisfactory dictionary definition: “man greatly concerned with smartness of dress, beau”) survived the over-exposed bon mots of such as Wilde and Baudelaire and permeated popular music from Little Richard and Billy Fury, through Hendrix and Brian Jones, to the original Glam Rock icons. From there, its influence skipped a generation of snotty punks in thrall to tatters and aggression before resurfacing in the New Romantic heyday of Spandau, Duran, Soft Cell, Adam Ant and – the most subtly effective of the troupe – Japan (David Sylvian understanding that its successfully effete projection required an intellectually aloof stance as much as gaudy gladrags). It’s arguably undergone another flurry more recently, watered down for Suede, Placebo, and others who may talk it but can’t walk it (even The Sweet looked more androgynous).

And if Bowie, Bolan, and Ferry did change lives and attitudes, personally and demographically, this is where they played their strong suit. The Mods (among whom Bowie, with The Manish Boys, and Bolan, with John’s Children, had flitted) had taken pride in appearance, and valued stylish self-betterment.

The art-school crowd (Ferry, Eno, Harley, Sparks) had taken on board Pop Art’s ice-cool reassessment of the validity of bold, glib marketing techniques. Now, with the “real” issues and campaigns that had so motivated the ’60s (between joints) seemingly resolved, and freedom of expression a passé given, the battlefield was a soft one, a matter of aesthetics. The twitches and traits of the theatre and art worlds entered the excitable realm of Hot Hits.

The early ’70s may have given us spacehoppers, hot pants, patched dungarees and bean-bag chairs, but they also gave us some silly, pointless stuff. Like, clearance to wear preposterous gladrags and look a proper pansy. While this resulted in more than one horribly misjudged party of shame for most of us, it meant that one had a much higher tolerance level for the quirks of others. Anything went. Dignity and restraint were on the first boat.

Denis Leary has said something that Ewan McGregor likes to quote: ‘‘In the ’70s we were in the middle of a sexual revolution, wearing clothes that guaranteed we wouldn’t get laid. Everyone looked a shambles.”

Except Ferry, who always looked immaculate. Whether carrying off a sheen-black jumpsuit or a white tuxedo, the man was always a cut above, a class ahead. How we admired his conceited cool. his parody (though we wouldn’t’ve known it) of slightly wasted elegance.

“With every goddess a letdown. every idol a bringdown, it gets you down,” the Ferryman sang on “Mother Of Pearl” from late ’73’s chart-topping Stranded. Before this, Roxy’s first two albums, Roxy Music and For Your Pleasure, had introduced them as experimental avant-garde acrobats of sound. These remain the critics’ favourites. But with Eno gone (Ferry was apparently jealous of Eno’s greater success with women: so much for the bisexual ethic there then) and carving his own niche as baldie boffin, Ferry’s Roxy were free to indulge the crooner’s overt romanticism and melancholy. Stranded is the true Roxy classic, a Max Ophuls epic where all the bridges sigh and at swish parties the poet falls fatalistically in and out of love nightly. Some of us were shaped and influenced by this myth to a perverse, unhealthy degree.

I have no doubt I would have allowed my life to be happier and more carefree had I not, on innumerable occasions, thought it preferable that it resemble the cool, airy, pained grandeur of a Roxy Music song. One learns too late that the cool and airy bits don’t come easily to real life, and the grandeur bit is also tough to achieve.

On the positive side, the pained bit is attainable enough.

ANDY’S CHEST

Bowie, for his part, had taken a number of cues from Andy Warhol’s Factory scene (whereas Ferry’s Pop Art references “were the brasher, less nocturnal Rosenquist, Johns, and Dine – anyone who echoed the hyper-real, faintly twisted sexual veneer of Hollywood and The Jazz Age). Warhol’s “superstars” – Jackie Curtis, Holly Woodlawn, Candy Darling – used glitter and transvestism as weapons in their war against convention. Bowie is reported to have started painting nails and shaving eyebrows after meeting this crowd.

He’d been into The Velvet Underground (and the fixation with whips, furs and a shadowy crossdressing demi-monde) as early as ’66, and admired Warhol’s toying with personae as puppets. On Hunky Dory he’d dedicated “Queen Bitch” to the Velvets (“white light returned with thanks”), who the New York Dolls were soon to replace as New York’s local left-field élite band. When he met Lou Reed, Bowie flirted and fawned. The habitually sarcastic Reed was sussed enough to realise that an artistic union between two self-confessed weird freaks might be strange and wonderful fruit.

Hence Transformer, produced by Bowie and Mick Ronson, and Reed’s biggest commercial success, which included such declarations as, “We’re coming out, out of our closets, out on the streets.” In July ’72, Reed – and a similarly rehabilitated-by-Bowie’s-adoration Iggy Pop – had been displayed as trophies at a Bowie press conference at The Dorchester. Reed now denies that much ostentatious kissing took place. He also denies that he resented Bowie’s taking the credit for much of Transformer, and bitched boisterously about this to the press. I know this because the sleevenotes l was asked to write for the current repackaging of Transformer were vetoed by the revisionist Reed himself on the grounds of “factual inaccuracies”.

So he’ll love Velvet Goldmine then, for the loose Curt Wild is as much based on Reed as on Iggy.

The lg’s unhinged stage performances (rolling around in gold body paint and broken glass) with The Stooges, the antithesis of ’60s feelgood surf music, had also caught Bowie’s eye, and the hyperactive Englishman was soon involved with Raw Power (later work on The Idiot and Lust For Life was much more fruitful). Bowie wished he had lggy’s carnal abandon, and found an element of it through playing Ziggy.

Tony DeFries, Bowie’s MainMan manager, had the gumption to maximise Bowie’s American obsessions, hiring a troupe of Warhol hangers-on and extras as “publicists”. Their unorthodox demeanour fanned the forest fire of Bowie’s mystique. And when he gave the song “All The Young Dudes” to Mott The Hoople, prior to this a run-of-the-mill West Country stodgerock band, he conjured up Glam’s international anthem. Young, foolish and slack, the glittering and priceless heard this as their very own jackboot-to-the-jacksy of ‘‘All You Need Is Love” and “Woodstock”.

It even mentioned T-Rex. If Mott, who’d already turned down the gift of “Suffragette City”, were in truth about as sexually ambivalent as Sid James (despite having one member called Ariel Bender), Ian Hunter at least had the grace, on their farewell single “Saturday Gig” (ironically their first with Mick Ronson) to croak: “Did you see the suits and the platform boots? Oh dear, oh gawd, oh my oh my! Don’t wanna be hip, but thanks for the great trip…”

CHILDREN OF THE REVOLUTION

So whatever did happen to the teenage dream? Is the world, as that notorious Glamster William Shakespeare put it, “still deceived with ornament”? Jobriath, groomed as the American Ziggy, retired in ’75. He was a decade too soon for Middle America. Renamed Cole Berlin, he died of AIDS in the Chelsea Hotel in 1983. Bolan died. Brian Connolly of The Sweet died. Alice Cooper plays golf. Lou Reed is in denial. Steve Harley says he doesn’t remember much because everyone was doing so much coke at the time. Queen saw a niche and cleaned up with “Bohemian Rhapsody”, which many consider Glam’s swansong. Freddie Mercury died. Mick Ronson died. Prince, in a big way, and Morrissey, in a pernickety non-visual way, tapped the legacy. Kurt Cobain and U2 were photographed wearing dresses: it’s no big deal. Mike Chapman went on to produce Blondie. Eno wants to be perceived as Einstein. Light metal acts from Kiss to Hanoi Rocks to Jane’s Addiction have dabbled with stereotypes, though thanks to Boy George, Marilyn and the New Romantics, it’s a moot point as to whether the “gender bender” is in any way startling today. This would explain the lack of reaction to the stalled “Romo” movement, and account for how Brett Anderson and Brian Molko can make “shocking” claims without having to back them up. It’d also explain why Manic Street Preachers elected to drop their provocatively glitzy manifesto and become a more commercial Big Country, yammering on about politics instead. I should declare a grudge: the Manics dissed my own attempt at a Glam Rock fling some years ago. They weren’t alone. It broke my tiny heart. Nobody had or has a greater genuine love for the genre than me. I’m the kind of person who gets really excited at receiving a letter from Bill Legend (one-time T. Rex drummer), who’s been to see sad “tribute” bands to both T. Rex and The Spiders (in fairness, T-Rexstasy weren’t sad at all: they knew what they were doing, they slid). Who found introducing Sparks onstage a couple of years back a genuine and profound honour. Who around the same time, in what was realistically my last gig before retirement (a nation mourned), got to sing “Pyjamarama”, in London. At the age of 12 l’d have said l’d die happy if I ever got to do that. And I wouIdn’t’ve been far wrong.

Glam Rock, for better or worse, taught me that you’ve got to jive to stay alive. That love is careless in its choosing; love descends on those defenceless. That the throne of time is a kingly thing, and the way somebody flips their hip can always make you weak. That it’s from yourself you’ve got to hide, and that there’ll always be a sheer, chic, teenage rebel of the week. That one thing we shared was an ideal of beauty.

And that life’s a gas.