Looking back on the mid-’80s, when he was leader of the Labour Party, Neil Kinnock vividly remembers the social and political landscape of the time. “We were in conditions of political and industrial turmoil,” he begins. “With high unemployment, increases in poverty not seen since the War and whole communities turned into dereliction by changes not only in the wake of the coal strikes but also the steel strike of the early ’80s. The rapid impact of unplanned and unsupported industrial change were evident.”

“There was something in the air in that period, 1984-1985,” agrees Billy Bragg. “It was incredibly intense. You have to see Live Aid in some ways as a reflection of that, because they were all the bands who didn’t want to get their hands dirty with the miners. But as me and The Smiths broke in 1984, we were very much of those times. We weren’t there alone, but in terms of addressing issues, The Smiths were at the forefront.”

“It’s something that I find quite amazing nowadays, how political the ’80s were,” admits New Order’s Stephen Morris, who played a Liverpool City Council benefit with The Smiths. “Greenham Common. Women camping outside, stopping Cruise missiles. That was brilliant. We took things more seriously then. We did loads of benefits, but everybody did benefits. I think maybe it was a continuation of the punk thing, Rock Against Racism.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_RrobS7cbEc

“There were people in the entertainment industry who were very disturbed by what was going on,” continues Kinnock. “When Margaret Thatcher’s premiership turned into ‘Thatcherism’ – in the wake of the Falklands War when the term started to be used – that became a pretty natural focus of antagonism for people who were becoming prominent in pop culture.”

“The Smiths were northerners with a tradition of stubborn working-class opposition, but delivered in a very nice and attractive way,” notes Richard Boon. “It wasn’t standing on the barricades, shouting. It was more subtle. The intent was to reach out to people who felt disenfranchised.”

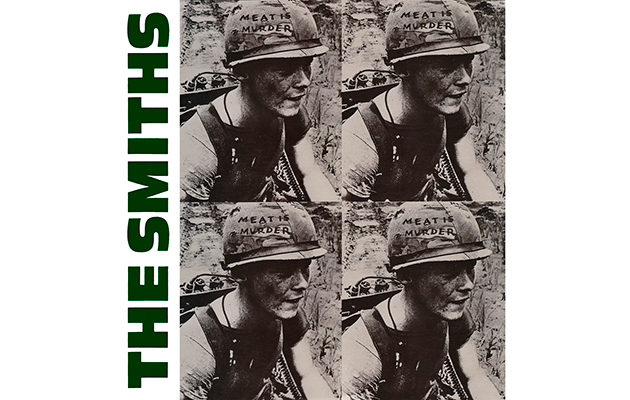

“Everyone was political to a degree, because everyone was united in their opposition to Thatcher,” says guitarist Ivor Perry, a friend of Morrissey whose band, Easterhouse, supported The Smiths on the Scottish leg of the Meat Is Murder tour. “Groups like ourselves and The Redskins were far more explicitly political because we were attached to ideologies and programmes of change. But The Smiths were more about lifestyle politics. It was important –but vegetarianism and the school system are not really hard politics, like economics or imperialism, or the subjugation of Ireland or apartheid. Then you had Morrissey’s very strong opposition to Thatcher, as well.”

Indeed, Morrissey’s views on Margaret Thatcher were keenly expressed in interviews from the time. “The entire history of Margaret Thatcher is one of violence and oppression and horror,” he told Rolling Stone in June, 1984. “I just pray there is a Sirhan Sirhan [Robert Kennedy’s assassin] somewhere. It’s the only remedy for this country at the moment.” In October 1984 – the same month The Smiths began work on Meat Is Murder at Amazon – the IRA bombed a hotel during the annual Conservative Party conference in Brighton, causing Morrissey to express his “sorrow” to Melody Maker that “Thatcher escaped unscathed”.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eR1VePIeWbE

“Morrissey was always very outspoken in interviews about Thatcher and the Royal Family,” recalls Andy Rourke. “Did I ever feel uneasy about any of his comments? No, not for my own feelings. I was 18, 19. I used to panic about what my dad might read. I was OK with it. As a band, we showed a great deal of solidarity and stood behind Morrissey with all his beliefs. We all had to have the same beliefs.”

“The rest of The Smiths were not political,” says Perry. “They liked getting high, smoking weed and drinking. No-one was sat reading political programmes. Morrissey himself was very into feminism and challenging writers. It was radical, but in a way that wasn’t going to affect the average guy on the street, a striking miner or whatever.”

“They were politically idealistic, young, fairly militant people at a time when the country was going through a lot of turmoil,” remembers John Featherstone, The Smiths’ lighting designer. “A lot of bands develop a persona as a band, which is a separate entity from their own individual beliefs. But The Smiths acted the way they did because they were the band and the band was them. They were largely self-managed at this time, too. So there was no manager saying, ‘You might not want to say that about the IRA attack on Thatcher.’ As a consequence, the way they acted was the way they felt and the way they talked. Things like Meat Is Murder was very much the way Morrissey and Johnny felt.”